As Michigan schools work to hire school counselors and reduce class sizes with their share of $6 billion in federal COVID aid, a group of education advocates say the state should do more to show that education funding reaches the most vulnerable students.

After decades of meager state education funding, Michigan should be prepared to raise its investment in schools once the federal funds run out, according to a new report from The Education Trust-Midwest, a nonprofit advocacy organization. But first, the group says, the state should begin publishing data showing how money intended to support students from low-income families or students with disabilities impacts their classrooms.

Nearly 30 years after Michigan established its current school funding system, a chorus of experts and educators say the state is due for another overhaul, this one aimed at supporting the students with the greatest needs. At the same time, that idea is being put to the test by the billions of dollars in federal COVID aid now flowing into the state: Much of the money is destined for districts with high concentrations of poverty.

Showing exactly where those federal dollars go would lay the groundwork for future increases in state education spending, said Amber Arellano, executive director of EdTrust.

She called for “a serious system of fiscal accountability and transparency,” which, she said would serve as an answer to “people in Lansing who say, ‘Oh, if we put more money into public education, we don’t know where it’s going to go.’”

Michigan’s education budget has grown in recent years — and this year especially, thanks to a state budget surplus — but it still doesn’t come close to providing the extra funding that education finance experts recommend for the most vulnerable students.

Michigan spent roughly $12,700 per pupil in 2019 on K-12 schools, a figure that includes state and federal funds, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s less than the national average, but more than 29 other states.

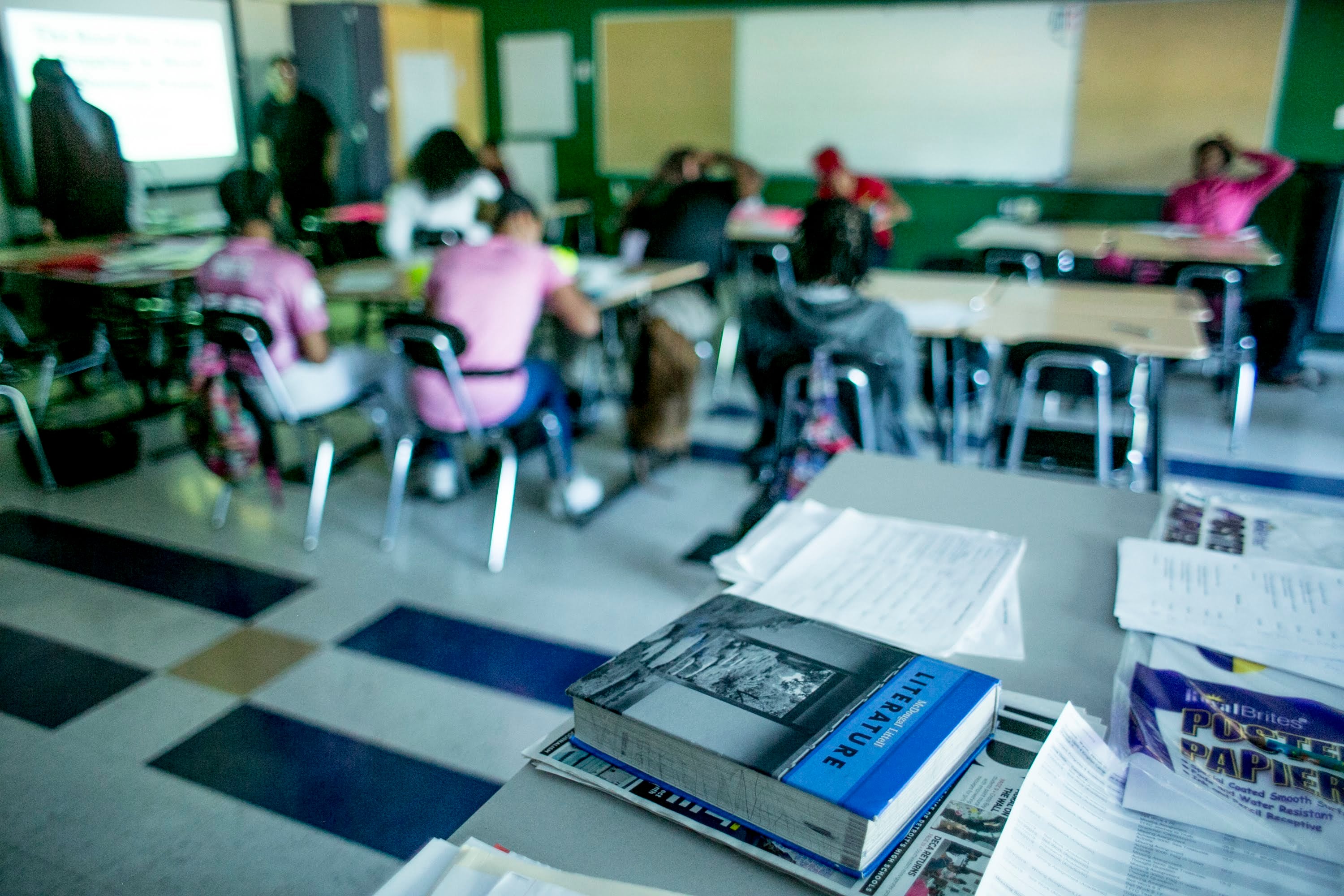

Within Michigan, school districts receive increasingly equal funding. But districts with more high-need students — English learners and students with disabilities, for example — receive very little additional funding. And because school buildings are funded through local property taxes, wealthy communities can afford to build up-to-date schools while children in areas with low property values often attend run down classrooms.

The EdTrust report argues that available public reports don’t show whether funds intended to help at-risk students end up in those students’ schools.

The data exists, even if it hasn’t been packaged for public consumption, said Craig Thiel, research director for Citizens Research Council of Michigan, a nonpartisan think tank. Michigan schools are required to account in detail for their spending, and districts are regularly audited. The state’s school accounting manual runs to hundreds of pages.

Thiel says it’s up to the state to package the available financial information to show the public how the money is being used.

“Transparency is not opening up the government checkbook,” he said. “It’s figuring out what info in that checkbook is important, and then figuring out how to explain to taxpayers why it’s important and how to understand it.”

Transparency is good politics, said Dave Meador, vice chairman and chief administrative officer for DTE Energy and a member of the Michigan Partnership for Equity and Opportunity, a coalition organized by EdTrust that is pushing for increased funding for vulnerable kids. He said it would be easier to win support from Michigan’s business leaders for a major new investment in Michigan education if the state expands its reporting on education spending.

“Now is the right time for Michigan to put in place a stronger fiscal transparency system that allows for the tracking of equity-focused dollars down to the school level,” he said in a statement, adding that such a system would also help track how federal pandemic aid is used.

Asking school leaders to produce additional reports — even as they face new accounting requirements related to federal COVID aid — would not be fair, said Peter Spadafore, deputy executive for public relations for the Michigan Association of Superintendents and Administrators, an advocacy group that represents district leaders across the state.

“We are not afraid of accountability; we submit very detailed spending plans annually,” he said. “I don’t think a lack of reporting is the problem with Michigan’s funding system, the problem is a lack of equitable funding.”