The year 2022 was another difficult one for education in Michigan. Educators, parents, and students were still dealing with the academic and emotional turmoil from multiple years of pandemic learning. And there was sobering evidence of just how much work must go into getting students back on track, despite billions of federal relief dollars that were designed to ease that process.

Through it all, the Chalkbeat Detroit team (get to know us here) was there for readers, asking the right questions, digging into the data, cutting through the noise, and helping readers understand what it all means. As the year comes to a close, it’s a good time to look back at what we accomplished.

Here’s a look at the stories (and photos) that reflect our best, most important work of the year on some key topics:

Chronic absenteeism causes alarm

At the end of the last school year in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, nearly 80% of the students were chronically absent. Such a high rate of absenteeism is costly, both financially and academically, and it is hurting efforts to help students recover from the pandemic. This issue isn’t just affecting Detroit. As Chalkbeat reporters Koby Levin and Ethan Bakuli reported, chronic absenteeism is reaching alarming levels across Michigan.

Chalkbeat will be diving even deeper into this issue in the coming year. If you or someone you know is struggling with school absenteeism, or if you’re an educator in a school that is working to get kids to school more consistently, you can fill out this survey or reach out to us at detroit.tips@chalkbeat.org.

COVID relief cash courses through Michigan

Michigan’s K-12 education system received $6 billion in federal COVID relief funds that were aimed at helping students and staff recover from the pandemic. That’s a lot of cash, and Chalkbeat partnered with Bridge Michigan and the Detroit Free Press to shine a light on how school leaders are spending the money, and whether the money is doing what it was designed to do.

Here’s what we found: Koby teamed up with Isabel Lohman from Bridge to report that while tutoring is a key piece of efforts to accelerate students academically, a lack of state leadership created a patchwork of programs that struggled to address learning loss. As districts invested more money in mental health services for students, Koby’s reporting identified a major challenge: A tight labor market was hampering districts’ efforts to hire additional staff. But they found some help among furry, four-legged friends. Meanwhile, Koby and Ethan wrote about how the COVID aid became a lifeline for financially troubled Michigan districts.

You can read all of our COVID aid spending coverage at this page, including about how the Detroit school district is investing $700 million to address its longstanding facility problems.

Teacher shortages draw multilevel response

Chalkbeat reporter Tracie Mauriello spent much of the year writing about a teacher shortage many Michigan school districts are experiencing, and what Michigan K-12 schools and colleges are doing to attract more people to the profession. In August, Tracie wrote about alternative certification programs that are providing an expedited route to the classroom, amid concerns about whether the route is rigorous enough. There were also stories about schools that were trying the “grow your own” route to promote teaching as a career, as well as a legislative effort that was supposed to ease substitute teacher shortages by allowing some support staff to become subs. Few took advantage of it.

Voucher-like initiative stalls

Betsy DeVos waded back into Michigan education policy this year by pushing the Let MI Kids Learn voucher-like initiative, which would have given tax credits to donors who contributed to so-called opportunity scholarships to help families to pay for private school tuition, tutoring, or other educational resources. DeVos, who was U.S. education secretary in the Trump administration, has long been a big proponent of school choice, including vouchers.

Backers of the proposal sought to put the initiative to voters in a ballot proposal — sometimes using misleading messaging — but didn’t turn in signatures in time to get it on the November ballot. A plan to have the GOP-led Legislature approve the proposal on its own during the lame duck session that ended earlier this month fizzled, because the state had not yet certified the petitions. Tracie and Koby noted that the proposal’s chances are slim for now, and with Democrats poised to take control of the Legislature in January, DeVos’ influence in the Legislature has dimmed.

COVID roils the classroom

The year 2022 began in the midst of a surge in COVID cases, thanks to the emergence of the omicron variant. The Detroit and Flint school districts canceled in-person classes for most of January, leaving students to learn online. Schools that kept their buildings open struggled with low attendance among students and staff who were affected by the virus. In a team story in January, Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti explained the difficult decisions he had to make. Later in the winter, Chalkbeat reporters in multiple cities, including Detroit, teamed up for a story on how the lingering pandemic was taking a toll on teachers in the classroom.

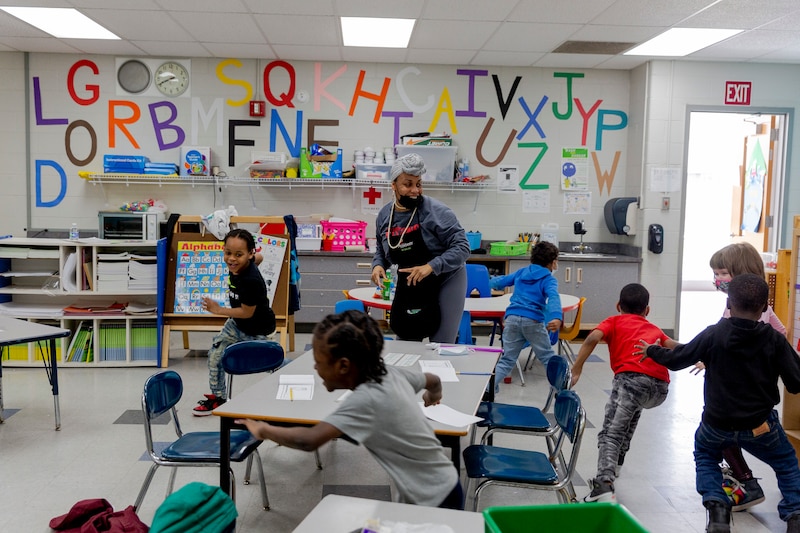

Early childhood education faces setbacks

Koby wrote several important pieces on early childhood education, including a look at how Detroit isn’t dedicating any of its COVID relief money to early childhood education. He also wrote about a pilot preschool program for 3-year olds that was at risk of ending, and the state’s $100 million plan to open new child care programs. Meanwhile, Chalkbeat co-published a Muckrock investigation that found Michigan’s child care crisis is worse than official statistics suggested.

Students, parents and teachers speak out

At Chalkbeat, we’re invested in elevating the voices of students, teachers, and parents who have a huge stake in the policy decisions that are made by administrators and lawmakers. In December, we published a question-and-answer piece from Ethan on Perriel Pace, an outspoken student activist who sits on the boards of more than a dozen youth-led organizations. Koby tapped into the joy students feel in elective classes like choir in a back-to-school piece. We highlighted multiple teachers and school leaders in How I Teach and How I Lead features, including an adult educator, the state’s teacher of the year, an art teacher, an English teacher, a principal, and two nutrition leaders. And we published first-person pieces from a Detroit high school student who urged the school district to recognize Pride Month, a Michigan middle schooler who wrote about the need for diverse books, a teen who wrote about social media use, and a teacher who wrote about the importance of school libraries.

Do you have a story to tell (or know someone else who does)? Reach out to us at detroit.tips@chalkbeat.org or lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.

Parents’ rights, book bans draw spotlight

Schools in Michigan, and across the nation, were frequently challenged this year by groups advocating for parents’ rights, and groups pushing to ban books that touched on LGBTQ themes and race. The issues heated up during election season, as Koby and Tracie noted in a story that looked at how Michigan school boards were facing a wave of culture war debates. After the election, Koby and Isabel from Bridge wrote an analysis that showed that conservative activists who were pushing parental rights lost far more local school board races than they won.

Students continue to struggle academically

The year brought more sobering data showing just how damaging the pandemic has been for Michigan’s students. Koby, Tracie, and Isabel from Bridge teamed up to write about the results of the Michigan Student Test of Educational Progress, which not surprisingly found scores were down sharply from before the pandemic. Tracie wrote about an uptick in the number of third graders whose reading scores on the state exam were poor enough that they could be held back (few were), thanks to the state’s Read by Grade 3 law. The disappointment continued this fall with the release of scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which found similar declines in achievement, particularly in Detroit.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.