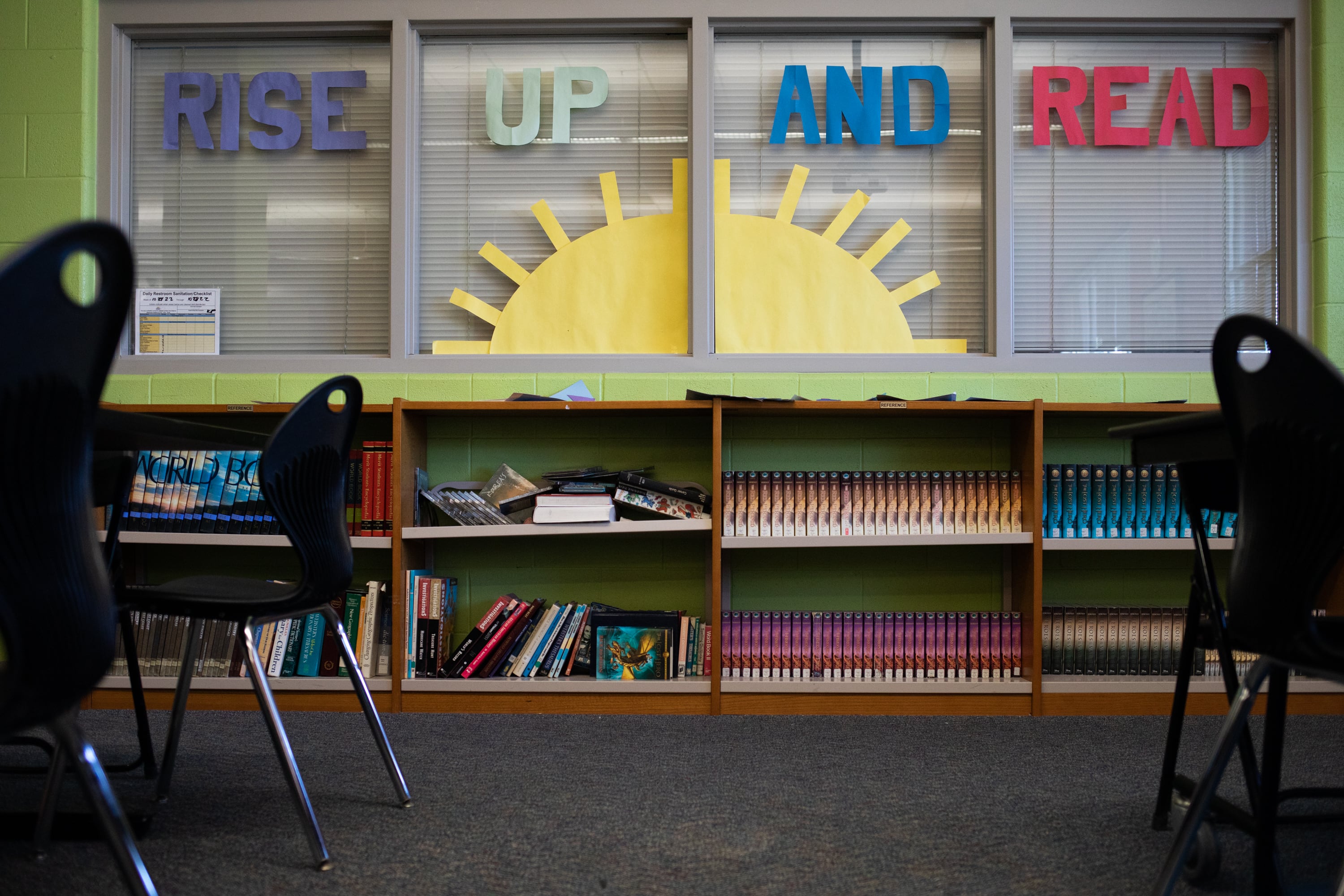

Josie Silver didn’t hand-select her classroom at Detroit’s Palmer Park Preparatory Academy, but she found it awfully coincidental that the room used to be the school’s library.

Nearly two years ago, at her former elementary school in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, Silver used grant funding from the nonprofit First Book to supply her second grade classroom with books. Since then, she’s actively been wrestling with how to instill an early love of reading in her students. Her goal for the near future: Create a fully functioning library at Palmer Park, where she teaches first through third graders.

“The absence of libraries is an atrocity,” Silver said.

“I cannot believe how many schools — not just in Detroit, but in Michigan — do not have functional libraries. I do see them as like an artery of the school.”

As an early elementary teacher, Silver regularly considers how to meet the academic and personal needs of her students as the district works to support children who may have fallen several grades behind in reading during the pandemic.

Last fall, Silver was named a Michigan Collaborative Teacher Leader. Each year, the program, co-led by the Education Trust-Midwest and Teach Plus, picks 20 educators across the state to meet with lawmakers, share their classroom expertise, and learn more about statewide education policies.

Silver spoke with Chalkbeat about work-life balance, graduate school, embracing phonics in the classroom, and adjusting to teaching in a Montessori program at Palmer Park.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How and when did you decide to become a teacher?

I actually have a bachelor of science in environmental studies. The way the teaching licensure program works was that at the elementary level you could add a licensure to any major. I would tell people in all my teaching classes, ‘Well, I’m never actually going to be a classroom teacher. I’m going to do outdoor education stuff or something.’ And then, once I was actually in the classroom, it was like, ‘I really like this’.

Were you set on doing early education?

I would say that I feel really confident and comfortable in the early [elementary grades]. I think there’s something about younger students that is really earnest. They’re very excited to learn. And if you pump them up, they are 100% with you. Being able to teach students at a time in their life when they’re generally really excited about reading, excited about math, excited about, honestly, pretty much everything — you can help them meet challenges ... and you can also help them develop their own identity

You previously taught at Durfee Elementary-Middle School before moving to Palmer Park Preparatory Academy this school year to work in their Montessori program. What brought about the shift in schools?

I taught for three years in the city. And then I went back to grad school for two years at [University of Michigan]. So last year was my fourth year teaching but my first year teaching in the pandemic. Last year was one of the first years teaching second grade that I felt like I was not able to meet all of those really different needs of my students using whole-group instruction.

That was really, really hard, and it felt like I was doing a disservice to my students who maybe were significantly behind grade level. They were totally capable, but they just hadn’t been to school during the pandemic, and that’s why they were behind. What really interested me about the Montessori program was not only the amount of student independence and choice but that each learner is on their own individual learning path. Yes, they may be working on similar activities, but it is so much easier to give each student what they need, at their level, to really build a foundation before trying to jump them ahead five steps that they’re not quite ready for.

How do you feel about the challenge for educators like yourself to make up for reading deficiencies students may be coming into your classroom with?

Especially last year, there are times when you just have to step back and recognize that there are deep systemic issues that I’m not going to be able to solve within my classroom. But I’m going to do as much as I can for the student. While they’re in my care, l am their advocate. I can empathize with things that are going on at home with their family — maybe financial instability or difficulties with transportation or things like that.

I also recognize that I really need to impress and stress how important going to school is and the work that students do there, not only because they’re young and they’re learning but also because it has long-term ramifications for their life. I think one thing that I did way more last year, or at least tried to do last year, was to be in touch with parents and give parents updates on their student’s progress all the time.

I feel like one way to feel like you’re building a stronger community, which would lead to higher academic outputs, is through building strong relationships with families who may have not always had a good relationship with school themselves.

I wonder sometimes for teachers that going the extra mile with families, how do you find a balance?

After teaching for three years, I was in grad school for two years, and that felt like a really nice break. And one thing that I noticed was how much freer I felt. I didn’t realize I’ve been carrying around the weight of worrying about a lot of my students all the time and thinking about them and what they’re going to do. I think there’s a social-emotional weight that teachers carry that is often invisible, and we don’t realize that we’re always holding onto — that definitely creates burnout.

What was the impetus behind going back to school?

I felt like I had some experience teaching but didn’t always have time to dig into research and didn’t have time to reflect on my practice. Going back to school really gave me that time.

The reality is you’ve got stolen moments in a coffee room with your colleagues, or you get a few [professional development] days a year. And during those days, you’re like, ‘Man, I wish I could go do stuff in my room.’ And so, for me, I needed to almost just disconnect from the classroom, and that was the easiest way for me to be thoughtful in my reflection.

What were some of the biggest misconceptions that you brought into teaching?

I definitely had never truly taught phonics until last year. I wasn’t really trained on how to teach phonics in my school program. So I think this past year — really digging into all of the articles coming out about the science of reading and how people are restructuring phonics — that’s been a huge difference.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom (or your school)?

My [third grade] students had been in kindergarten when they were first pulled out of school. When we went on our first field trip, a lot of them had never been on a school bus, and they were so excited. They had never had a picture day. I remember doing an activity around Martin Luther King Jr. Day last year about the dreams people have for the world. But several of them in my classroom were, like, ‘I dream that COVID is gone.’ And they were drawing people without masks. Because to them, COVID was such a significant portion of their life thus far.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received, and how have you put it into practice?

I think that people stressing to me that I can’t carry all the baggage a student comes with in my classroom, but I can teach them strategies and make school the safest place it can be for learning and living. I can try to check in with resources, but I can’t carry food insecurity, housing insecurity, too many siblings living in the same house, and things like that. I can focus on giving them as much care and attention as I can at school so that they can thrive academically.

Are there certain areas where you hope to leave an impact?

I would really like to be a part of creating a functional library at our school again. I know I can’t make funding for a librarian appear, but I am working to figure out how we can use both students and maybe volunteers so the burden isn’t imposed on staff.

It’s crazy to me that we look at literacy rates around the city, and we talk about curriculum, and I think those are important, but what about libraries? I think that they’re hugely important within schools, and I would really like to be a part of building ours back. I know several DPSCD schools that have done that in the past couple of years. Hopefully, that becomes a larger trend.

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.