Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

Nearly 28% of Michigan students were chronically absent during the 2024-25 school year, the third consecutive year the rate has dropped.

But the rate is still significantly higher than it was before the pandemic began, when 19.7% of students were chronically absent during the 2018-19 school year, according to data released Wednesday by the state Center for Educational Performance and Information.

Chronic absence, which impedes students’ ability to learn and creates instability in the classroom, is a concern in a state where academic performance has been lackluster.

“It’s important for communities to continue to collaborate to emphasize the importance of good attendance and assist children most in need of attendance support,” State Superintendent Michael Rice said in a statement Wednesday.

Students are considered chronically absent in Michigan if they miss 10% of the school year, or roughly 18 or more days in a typical 180-day year.

Michigan had one of the highest rates of chronic absenteeism in the nation at the height of the pandemic, when the rate was 38.5% during the 2021-22 school year. The rate dropped to 30.8% in 2022-23 and 29.5% in 2023-24.

The state’s progress last year was similar to the previous two years, said Jeremy Singer, assistant professor of educational leadership and policy at the University of Michigan-Flint.

Singer, who has conducted extensive research on attendance via Wayne State University’s Detroit Partnership for Education Equity and Research, or Detroit PEER, said that progress still is slower than “we want to see on average.”

“But obviously it’s a good thing to see things moving in the right direction.”

A Chalkbeat analysis of the data found:

- 263 district and charter schools had chronic absenteeism rates above 36%, which Singer considers “very high.” The average rate among those districts and charters was 51%.

- The highest rate of chronic absenteeism, nearly 93%, belongs to Blended Learning Academies Credit Recovery High School, a charter school, which appears to have campuses in Lansing and Livonia..

- Nearly half of Black students statewide were chronically absent during the 2024-25 school year, compared to 34% of Hispanic students, 34% of Native American students, 20% of Asian American students, and 21% of white students. The rate for Black students is above the pre-pandemic level of 39% in 2018-19.

Despite the problem, more than half of the school leaders who responded to a statewide survey by researchers at Detroit PEER said they haven’t received any guidance from their districts on how to improve students’ attendance.

Even among those who did receive guidance, just 13% said the guidance was very helpful, Singer said.

“That might be because the guidance is unclear, or maybe it’s because they feel like what is being recommended isn’t working as well as they were hoping.”

Still, simply providing stronger guidance won’t solve the problem, because schools alone can’t solve chronic absenteeism, something Singer and research partner Sarah Winchell Lenhoff, the Detroit PEER director, made clear in a book they released earlier this year.

“I do think clear guidance can help, especially if it helps schools be thoughtful about what strategies they prioritize and how they allocate their resources,” he said..

Detroit PEER sent surveys to around 2,700 school leaders across Michigan. About 41%, or 1,143, replied, giving the researchers a broad look at how schools in the state are addressing chronic absenteeism. The research is ongoing, but initial findings were recently released.

Districts serving impoverished communities have more to overcome

A lack of accessible transportation, parents’ inflexible work schedules, health concerns, and unsafe routes to school have long contributed to high levels of chronic absenteeism in impoverished communities.

The negative effects of the pandemic, which disproportionately hit low-income households, exacerbated existing systemic inequities.

Michigan’s recently released data, however, shows many of the districts with the most to overcome outpaced the rest of the state in improving attendance – like the Detroit school district.

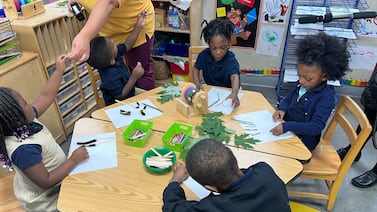

Before the pandemic, the Detroit Public Schools Community District, where 84% of students come from low-income homes, made progress reducing absenteeism with wraparound services for families, hiring attendance agents, and community partnerships.

That momentum was lost in the 2021-22 school year, when the rate of chronic absenteeism shot up to 76.7% in the school system largely due to quarantine rules at the time.

Last year, for the first time, students in the district were chronically absent at a lower rate than in the years preceding the pandemic, the state’s new data shows.

In 2024-25, 60.9% of students in the district missed 10% or more of days in the school year. The rate was 1.2 percentage points lower compared to the 2018-19 school year – the last year before COVID upended in-person instruction.

“Our improvement is rooted in our intentional efforts to expand services to students and families, changing staff mindsets about owning the student attendance improvement process, and increasing family accountability regarding their children’s attendance,” Superintendent Nikolai Vitti told Chalkbeat in an email.

The school system has used a multilayered approach to improve attendance in the years since then , including connecting directly with families to help meet their needs, fostering more partnerships, financial incentives for students, and installing laundry machines at schools, among others.

In the Lansing Public School District, where more than 87% of students are from low-income homes, the absenteeism rate is also now lower than it was before the pandemic. The percentage of kids missing too much school has dramatically decreased from high rates in the early days of COVID.

In the 2021-22 school year, more than 90% of students in the district were chronically absent. Last year, the rate decreased by nearly 38 percentage points.

The district uses a tiered system of support for kids who are at risk of missing too much school with classroom, school, and district-level strategies. The system ranges from informing families on how they can ask for help managing barriers to creating attendance success plans.

Classroom teachers reward students who improve their attendance. At the school level, families of students who are missing three to four days of school a month may get wake-up robo calls as a “friendly nudge.” At the district level, administrators follow-up on referrals to the Office of School Culture’s Attendance Team to set up parent and student meetings.

“We are so proud of our students, families, and educators, who have focused deeply on making every day count and having as many of our students show up to learn,” Benjamin Shuldiner, superintendent of the district, told Chalkbeat in an email.

Some districts improve attendance with mental health supports, accountability

James E. Anderson, superintendent of Wyandotte Public Schools, told Chalkbeat mental health concerns have been the cause of many instances of chronic absenteeism since the pandemic.

“More and more students are having anxiety about something at school,” he said. “It may be peer-to-peer interaction or not wanting to get back into the habit of going to school everyday.”

That aligns with what researchers have learned from the Detroit PEER survey. Researchers provided a list of 33 potential barriers and asked the school leaders to select the top five most common. The survey responses found 43% of school leaders selected mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, as a top barrier.

Chronic absenteeism in the suburban school district jumped to 45.7% in the 2021-22 school year – more than 20 percentage points higher compared to the years before COVID. Last school year, the rate stabilized at 27.8%.

Anderson said the district addresses absenteeism with a simple system.

When students are absent five times, they receive a letter breaking down how many days of school they will miss by the end of the year if they continue missing days at their current rate.

By 10 absences, administrators ask for a meeting with the students’ family to determine what challenges they are facing. The district connects the students with resources based on their needs, such as school or community-based mental health services or arranging transportation, like carpools with neighbors.

At 15 absences, a ticket is issued via a local ordinance. Families must then appear in court to explain why students aren’t getting to school. In some cases, fees are issued.

Statewide survey show schools taking similar approaches

Initial findings from the Detroit PEER research indicate that there is little differentiation between schools in how they’re addressing chronic absenteeism.

“Schools are looking at and are approaching the issue relatively similarly,” Singer said.

Singer said he isn’t sure yet whether that’s a good or a bad thing.

“It worries me a little bit because I think what it communicates is that schools are still trying to figure out how to solve it and so they’re doing a lot of everything.”

The report noted that “the most common practices centered on communication, social-emotional learning, and mental health support” but that “resource-intensive practices like home visits or arranging transportation were less common.”

The least common practices, Singer said, are strategies related to improving conditions within schools so that students have a more positive experience.

“That’s something that’s within the school’s control,” Singer said.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.

Hannah Dellinger covers Detroit schools for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.

Sept. 18, 2025: This story was updated with a comment from Superintendent Nikolai Vitti.