Months after South Bend Schools took its first step toward partnering more closely with local charter schools, one of its potential partners is trying to defeat the district’s referendums ahead of Election Day.

South Bend is asking voters Tuesday to approve two property tax increases worth a total of about $220 million over the next eight years. But the referendum campaign has revealed that at least one attempt to reform the district by creating an innovation school — managed by a charter operator but considered part of the district — is unlikely to become reality.

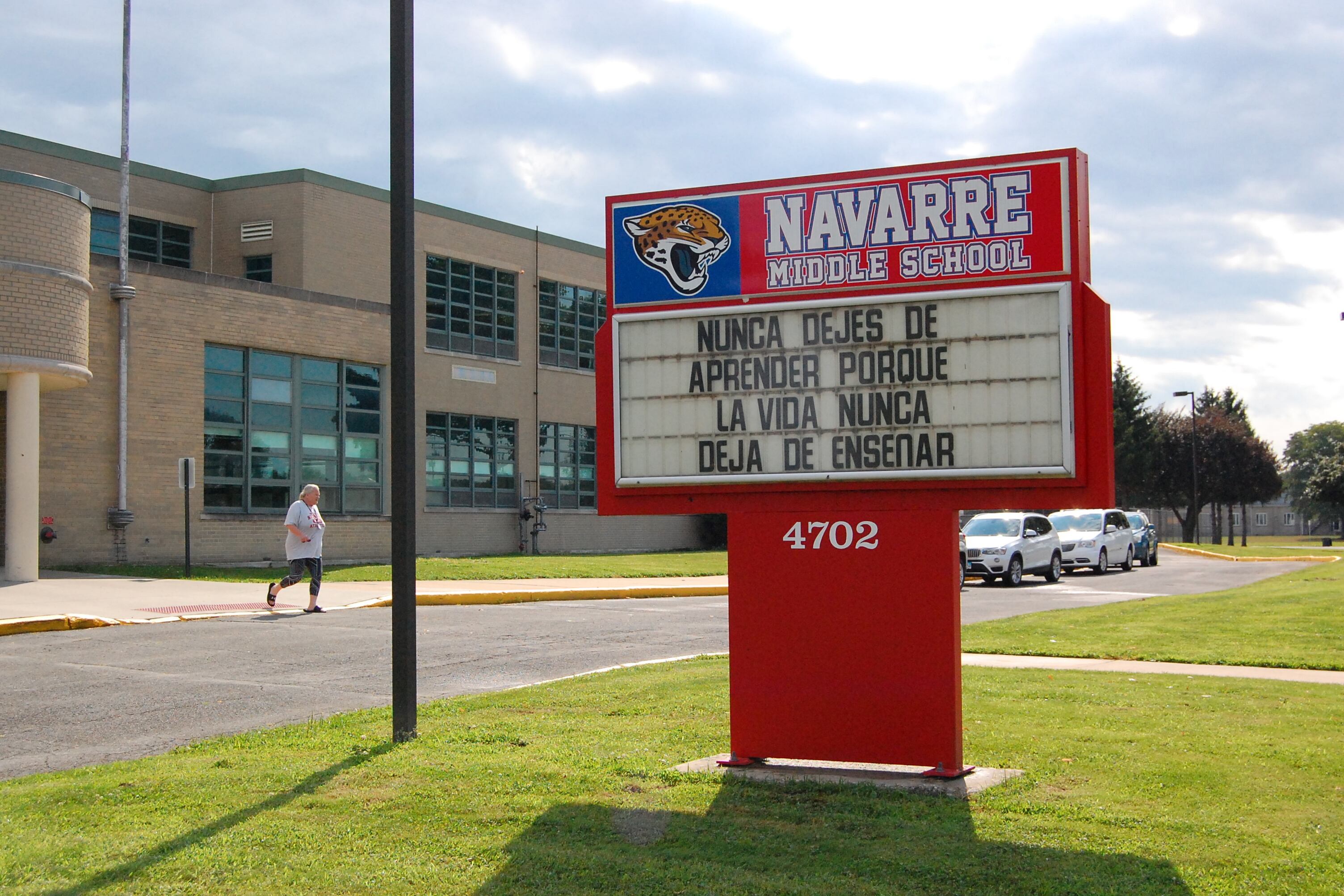

The ballot measures, which would fund security updates and the hiring of more teachers, come at a critical moment for South Bend, following years of dropping enrollment and low standardized test scores. Administrators are bracing for big financial hits while also trying to turn around academic performance. The district is under pressure to make changes after narrowly avoiding state takeover of a middle school after it received consecutive failing grades from the state.

“I believe that it is an important moment, not only for our schools but for our neighborhoods and city,” said Mary Downes, who co-chairs the committee campaigning in favor of the referendum. “I think there’s a very strong commitment and passion to have public education be very solid, and an equal access to education for all.”

But the referendums face opposition led and self-funded by Larry Garatoni, the founder and board president of three local charter schools. He says the district lacks a clear plan for change. His opposition presents an unexpected dynamic, considering that he met with Superintendent Todd Cummings in October to discuss an innovation partnership.

Garatoni said he never had “meaningful negotiation” with the district about partnering with Success Academy, which serves grades K-5, and Career Academy middle and high schools, which serve grades 6-12. The school board also formally voted in February to cut off discussions with another potential innovation charter school: Purdue Polytechnic.

South Bend would have been the third Indiana district to pursue the controversial strategy. Only two districts in Indiana have innovation schools: Indianapolis Public Schools, with 21 such schools, and Gary Community Schools, with one.

For South Bend, the partnership started as an effort to boost enrollment and improve education for students. Cummings didn’t say what happened after his initial meetings with Garatoni. But he did say that the current opposition would make partnering impossible.

“I can’t imagine those conversations will continue as long as there are giant ‘Vote No’ billboards in town,” he said.

According to election committee filings, Garatoni has contributed $30,000 to his anti-referendum campaign, which has no other donors, and has spent around $10,000 so far. The pro-referendum committee has raised nearly $17,000 and spent more than $14,000.

Garatoni acknowledged that his growing network of charter schools, which together serve around 1,300 students in grades K-12, could benefit from the referendum failing, because it might force the district to close more schools. Under state law, empty school buildings are available for charter schools to purchase for $1. But Garatoni said that’s not why he opposes the referendum.

“I’m not trying to harm the schools,” Garatoni said. “Basically, I’m saying fix the schools. If they get the money then they can coast again and they won’t confront the issue.”

Garatoni points to state data, which shows that South Bend spent $9,654 in funding per student in 2019 — more than neighboring districts — but still has low passing rates on state standardized tests, with black and Hispanic students scoring lower than their white peers.

But advocates say comparing the districts to its wealthier neighbors is unfair. South Bend has more low-income students and English language learners, which requires they offer more supports and therefore grants them more funding under the state formula. Indianapolis Public Schools, for example, spent $14,469 per student in 2019.

“Schools in neighborhoods of high poverty have the need to make class sizes smaller, to work with social emotional needs, have robust food service programs, robust programs for students who are learning to speak English,” said David Marcotte, executive director of the Indiana Urban Schools Association.

Providing extra support means those districts need more funding, Marcotte said. In Indiana, urban schools have faced the greatest competition from private and charter schools compared to rural areas, where fewer have opened. In a state where funding follows the student, losing students to other schools means funding losses for urban districts that are difficult to plan for or respond to quickly, he said. More than 7,000 students who live in South Bend don’t attend school in the district, according to state data.

Passing a referendum could be even more critical for districts now that the coronavirus is threatening state funding. School budgets in Indiana largely depend on state sales and income tax revenues — both of which have taken a hard hit after businesses closed and unemployment soared.

Property taxes likely won’t see an immediate impact from the virus, which makes passing a referendum an attractive option. But it will likely be more difficult to sell families on paying more in taxes, Marcotte said, as hours are reduced or companies lay off workers.

“It’s a whole different conversation,” he said. “Now families are going to say, ‘I support the schools, but can I afford to do this?’”

If the referendums are approved, South Bend would receive a total of $54 million for construction, which the district said would be used for security updates to its buildings, and $20.8 million for operations each year. The money would be used to fill teaching vacancies, increase salaries and maintain programming, according to the district website.

It would also offset an anticipated $16.6 million loss next year, in part because the county’s 10-year exemption from property tax caps will end.

Taxpayers wouldn’t see the full increase in their bill because the measure would largely neutralize expected savings from the property tax caps. According to the district’s tax calculator, the monthly property tax bill for a home valued at $110,000 would increase by about $13, from $68.25 to $81.33.

As for innovation schools, Cummings said the idea isn’t entirely off the table.

“We’re open to options that help us turn our schools around,” he said. “So as we get past June 2 [Election Day] and we look at the academic needs on the table, we are open to doing what is best for students.”