Many officers who patrol Indianapolis Public Schools see themselves as educators and informal counselors, in addition to law enforcement officers. Most students, staff, and parents, however, see them strictly as police.

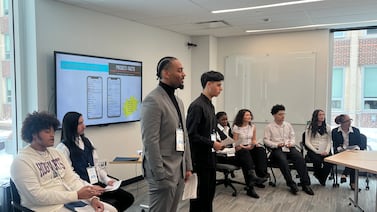

That divergence in perception is among the findings of an independent review of the district’s security force by Indiana University’s Public Policy Institute.

The report, presented to the school board Tuesday, noted other disparities in outlook: While 88% of the district police officers said they collaborate effectively with school personnel, just 61% of staff agreed.

The report includes recommendations on oversight, training, accountability, and more.

“I think it’s a great study. It provides lots of context,” said board Vice President Evan Hawkins. The district administration and Police Chief Tonia Guynn will review the findings and discuss possible actions, he said.

Board member Taria Slack said she hopes that more collaboration will lead to more trust between officers and students, “so we can de-escalate a lot of situations we have.”

Researchers found ambiguity and, in some cases shortcomings, in police roles, protocols, and training in racial equity and fighting implicit bias. “Combatting systemic racism requires ongoing learning, reflection, and intentional implementation of core concepts in their work,” the report noted.

The report notes a lack of clarity about when officers should and should not use force.

Concerns about campus policing, including racial disparities in discipline and arrests, have prompted the district to analyze how its police operate. The goal is to decrease suspensions and expulsions, improve school culture, and nurture students’ well-being.

But restorative justice — practices touted as alternatives to traditional discipline, citation, and arrest — has fallen short, the report noted.

“We have all but stopped implementing it because it takes a tremendous amount of time and cooperation with students, staff, and families,” one officer told researchers.

From 2017 through 2020, the district’s Black students were seven times more likely to be arrested than were white students.

The report recommended differentiating between student misconduct and criminal offenses, providing guidelines for using force, and involving parents and school staff in hiring officers. It also suggested the district step up training and collect data on policing. And it advised convening an advisory committee to recommend whether officers should wear uniforms and carry guns and tasers on campus.

Indianapolis Public Schools might consider rebranding its law enforcement “to create a shift in department culture and mindset,” the report suggested.