Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

To get students to attend summer school, the staff at Global Preparatory Academy in Indianapolis do whatever it takes: Flyers and messages, conferences, and even stopping parents to talk at pick-up and drop-off.

They strongly encourage some students to attend for “more at-bats,” or to practice key reading skills before taking the state’s third grade reading test, known as the IREAD. Others are there to prevent summer learning loss, said Assistant Principal Jessica Pumphrey.

Known as Summer Learning Labs, — a project of The Mind Trust and United Way of Central Indiana — similar sites around Marion County are open to all. But they were created for students in neighborhoods where families live above the federal poverty threshold — $31,200 in annual income for a household of four — but can’t afford all their household needs, like child care and rent.

As a new law goes into effect in Indiana that could lead to an increase in the number of students who are held back because they don’t pass the IREAD-3, it will likely have the greatest impact on students who come from low-income families.

This group made up nearly three-quarters of the over 13,000 students who didn’t pass the IREAD in 2023. They also made up roughly 300 of the 400 total students who were retained in third grade that year.

Research isn’t clear on how the tougher retention criteria will likely affect these students in the long run. But education advocates are optimistic that the other provisions of the law — like earlier identification, intervention, and summer school — will make a positive impact on their reading skills long before third grade.

Still, those efforts will take a significant investment in summer school and instruction that’s based on the science of reading.

Beginning next summer, the law mandates summer literacy instruction for students who are struggling in reading, but it won’t be clear how much funding will be available for these programs until lawmakers pass the next biennial budget in 2025. The current state budget for summer school doesn’t fully cover summer school costs.

At Global, the free program’s enrichment activities, field trips, and meals are key for families at a school where the majority of students receive subsidized meals.

And similar services may be critical for a growing number of children.

Around 16% of Indiana children live in poverty as of last year, said Tami Silverman, president and CEO of the Indiana Youth Institute. In 2022, 15% of Indiana children were in poverty.

Those children are “most likely to have issues with transportation, food, and shelter, they may have to move more frequently, which impacts academic success,” Silverman said. “In order to move the needle on retention, we need to talk about poverty and transportation and healthy foods and mental health care. It’s all intertwined.”

Retention may improve short-term academic performance

While retention has long been part of Indiana policy, it has dropped off in practice, with thousands of students “socially promoted” over the years. Now, students must pass the IREAD-3 to move on to fourth grade, unless they meet one of a handful of exemptions. The policy begins in 2025-26, based on 2024-25 IREAD results.

In 2023, 72% of the students who didn’t pass the IREAD and 74% of the students held back came from low income families.

A complex web of factors, rather than a single reason, connects poverty to lower academic performance, said University of New Hampshire professor NaYoung Hwang, who’s the coauthor of an Annenberg Institute at Brown University study on retention that used Indiana student data.

Oftentimes it’s educators who spot signs that economic factors are affecting a student’s academic performance, said Lillian Barkes, a former elementary teacher who’s now CEO of the Indianapolis-based tutoring organization Listen to Our Future.

“A student comes in upset, what do you do? Are you asking questions, or are you assuming a student is lacking the will?” Barkes said. “You start with Maslow’s hierarchy: Do you feel safe at home, do you feel safe coming into this room, did you sleep last night, did you eat this morning?”

Some research also suggests that students with highly educated parents are less likely to be held back because their parents are more likely to take advantage of exemptions to these policies. Effectively, this means that retention policies are “enforced differentially depending on children’s socioeconomic background,” according to that study.

But does retention work? Hwang said her study showed retention in third grade improved both math and reading scores for all students, including those who come from low-income backgrounds.

“In the short-term, there is a huge positive effect. It benefits basically everybody,” Hwang said.

However, few studies have followed students who were held back a grade through high school and graduation, Hwang said. One such study in Florida found that the positive effects on achievement fade out by high school, while others have noted a potential cost to students entering the workforce a year later.

Research has also found that holding kids back in later grades can lead to worse behavioral outcomes — including higher dropout and suspension rates — than holding kids back in third grade, Hwang said.

“Timing is very important,” she said.

Summer school reading programs start in 2025

Beginning next year under the new law, all Indiana schools, including private schools, must offer a summer school program based on the science of reading to all second and third graders who don’t demonstrate proficiency on the state reading test.

The programs, including the ones at private schools, are supposed to receive priority reimbursement from the State Board of Education. But it’s not clear how much funding will be available until the 2025-27 budget is passed next spring.

In 2023, 309 Indiana schools requested and received $18.3 million in reimbursements from the state’s summer school fund. That amount was 65% of schools’ $28 million in actual costs for summer school.

Meals and transportation are not eligible for reimbursement.

If lawmakers don’t appropriate enough money to cover these costs, schools would have to fund the rest through other means.

The Indy Summer Learning Labs began in the summer of 2021 as a collaboration between The Mind Trust and United Way of Central Indiana. They’re funded through federal pandemic relief money that’s expiring later this year. That means it’s critical for lawmakers next spring to appropriate money to keep the programs going after 2025, said Kateri Whitley, senior director of communications at The Mind Trust.

Most of the lab sites are free or low-cost for students, and the program this year is expanding beyond Marion County.

In 2023, around 89% of the 5,000 students who attended learning labs qualified for subsidized meals. This group improved by 24 percentage points in English scores, and by 23 percentage points in math, according to data from The Mind Trust from an assessment it gives students. A state education department analysis of ILEARN data from 2021 and 2022 about students in the labs also found gains.

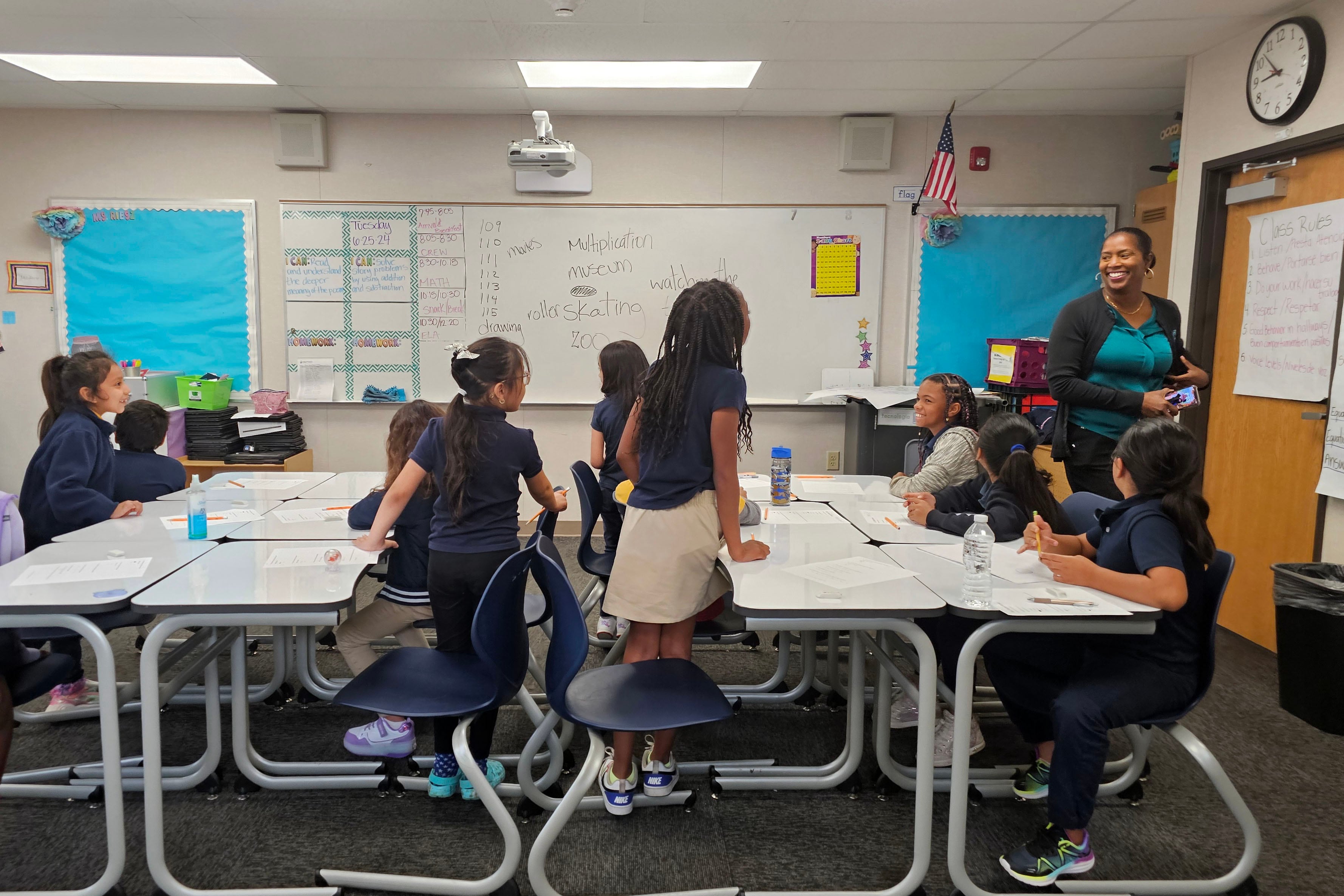

At Global Preparatory Academy, some of the 115 students at the summer lab work on remediating literacy skills to prepare for and retake the IREAD, while others work on concepts to prepare for their next grade level.

“Students in poverty, students of color, might have less access to acceleration because their schools have fewer resources,” said Jazmin Sanders, manager of school support and incubation at The Mind Trust.

The cultural relevance of the work is also important. On a recent Tuesday, a classroom of rising third graders read “The Tales of Our Abuelitas” by Alma Flor Ada and Isabel Campoy, while rising fifth graders discussed the discrimination against Jackie Robinson, who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier.

“Literacy is easier when you make a connection,” said Pumphrey, the school’s assistant principal.

Identifying students and notifying parents about reading concerns

Other provisions of the law require schools to identify students at risk of not reading proficiently in earlier grades, and notify their parents of their assessment results and literacy skills. How that will be done is largely up to schools.

Silverman, of the Indiana Youth Institute, said the youth-serving organizations she works with routinely say engagement is one of the biggest hurdles to helping low-income families access resources.

While many schools offer these supports, it’s important for families to feel invited to access them via personal connections with teachers, counselors, and other school staff, Silverman said.

The same goes for the new programs that will address reading skills.

“If a young person’s reading levels are lagging, how are we adjusting outreach knowing that might be an issue within the home?” Silverman said. “If our hypothesis is that tutoring and summer school can help, how can we increase access? How can we increase comfort in using those services?

Freedom Readers, a program from the education nonprofit RISE Indy, takes steps to address those questions. It teaches Indianapolis parents to first request and interpret their child’s assessment results, and then take steps to practice reading skills at home.

The goal is to help parents understand their role in tackling the larger literacy crisis, said Jasmin Shaheed-Young, founder of RISE Indy, while at the same time making test results easier to understand for all families.

“We want to empower them with the information that could combat the challenges and disparities that we see,” said Shaheed-Young.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.