The Newark elementary school teachers gathered in a large circle at the center of a classroom, where student desks lined the perimeter and a makeshift sign on one wall read, in part, “Step up, step back and create a safe space.”

It was time for “morning check-in.”

One by one, on this Friday morning in August, they shared their feelings.

Some were happy to be wrapping up a second week of professional development. Others were excited for the weekend. A few were feeling tense from a difficult morning at home. Between each turn, the rest of the group would share words of encouragement or validation.

“We’re happy for you.”

“Thank you for sharing and being here with us.”

“We see you. We hear you.”

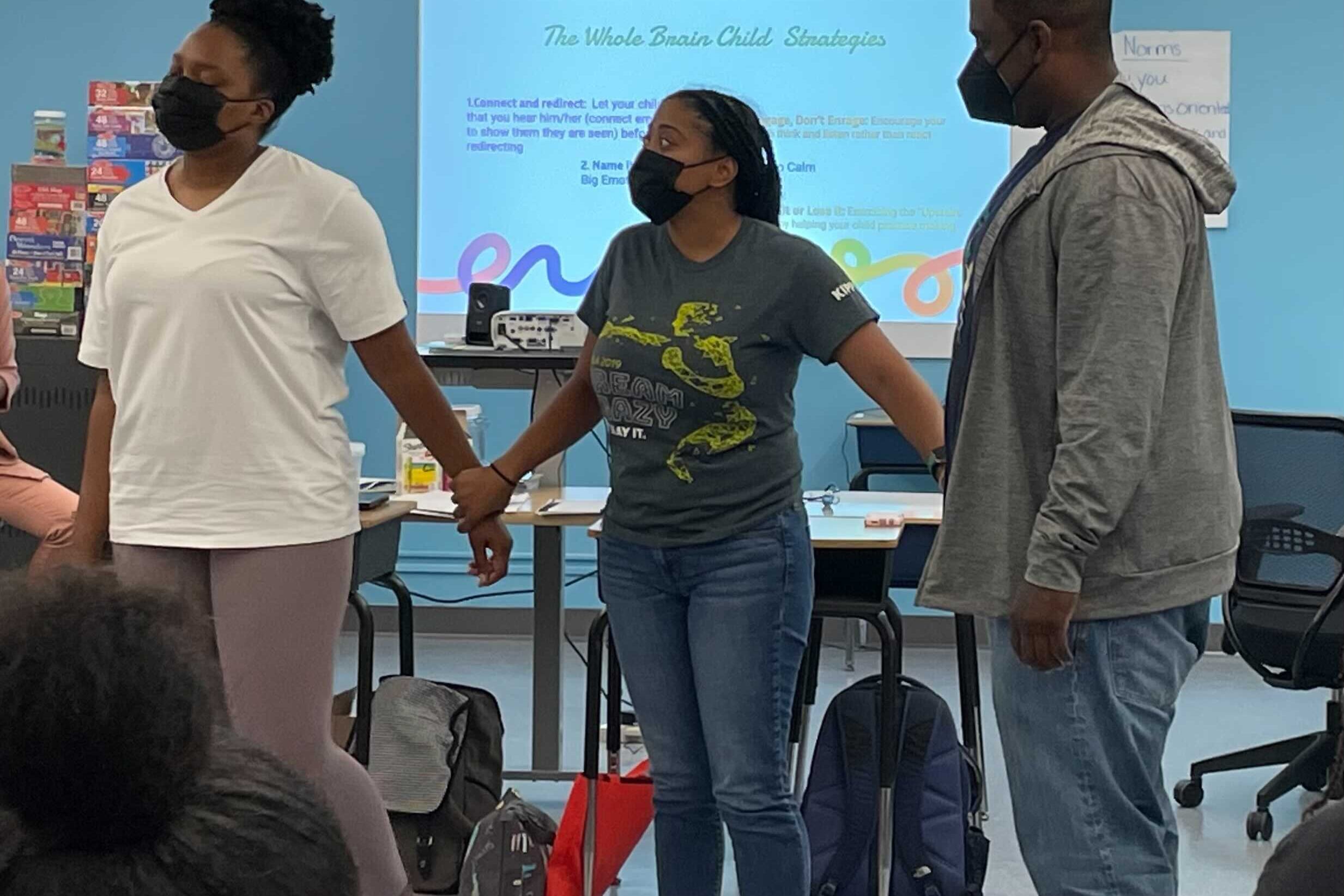

The ritual was part of a day of professional development for the teachers of KIPP Truth Academy, the charter school system’s newest K-4 school in Newark.

The morning check-in, which the teachers plan to incorporate in their classroom routines this year, is meant to create an intentional safe space and time to share feelings, offer compassion, and establish a welcoming environment.

In Newark, as in schools across the country, elementary school educators have been preparing for how to best help their youngest students transition to being in the classroom on a full-time basis for the very first time or first time in 17 months. While the pandemic continues to be a threat to their own health and that of their families, many students are carrying into the classroom the experience of facing a crisis at home spurred by COVID and other traumatic events.

As back to school season gets underway, a rise in the highly contagious Delta variant has caused more anxiety and fear in school communities. Gov. Phil Murphy has mandated universal masking in schools, as has Newark Superintendent Roger León for the city’s schools, and a state order requiring vaccinations for educators is expected to be announced soon.

Most charter school students in the city returned to school this month, while Newark public school students await their first day of school on Sept. 7.

For the first time in nearly a year and a half, students in New Jersey won’t have a remote or hybrid option for instruction, and they’ll need to be in school full-time, under Murphy’s orders. In the midst of an ongoing health crisis, elementary school educators plan to focus on addressing the social and emotional needs of their students.

“We need to give kids a chance — even though they’re young and may not be able to articulate fully — to share their feelings and their stories,” said Maurice Elias, a psychology professor at Rutgers University who directs the Rutgers Social-Emotional and Character Development Lab.

The first few days and weeks of school should prioritize social and emotional learning over academic instruction, he said.

“Getting kids back into the academic routine is not as important as them feeling comfortable,” Elias said. “This is a process. It’s not a moment.”

Conversations before learning

KIPP Truth Academy School Leader Princess Fils-Aime co-led the professional development session that Friday morning in August with a focus on “educating the whole child,” which drew strategies from the book “The Whole-Brain Child,” by Daniel J. Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson. The book explains how children are ruled by “the right brain and its emotions” over the “logic of the left brain” and offers ways to share healthy emotional skills so that kids can feel better able to cope with their feelings.

In their experiences, the teachers in the room shared, children don’t tend to wait for the most convenient or appropriate time before they feel an urgency to share or express their feelings, which can manifest in different ways.

Rachel Fergusen, a third-grade teacher, asked, “When more than one kid in a classroom is feeling pain or hurt or strong emotions, how do we then manage the prioritization of the pain? Whose feelings get addressed first?”

Fils-Aime suggested leaning on the help of the teacher assistant in the room. She emphasized that students will need to feel heard before they can begin to fully absorb academic instruction.

“They’re going to need us to be understanding, to show them grace and patience,” Fils-Aime said. “You have to make the time for the conversations because the learning won’t happen if the conversations don’t happen first.”

Sheyla Riaz, director of social work at KIPP New Jersey, said the school system has incorporated social and emotional learning into the academic curriculum so that feelings don’t get compartmentalized into just one part of the day.

“If we’re reading a story, we’re asking our kids to reflect on the characters’ experiences, how the characters engage with others, and how the characters manage their stress,” Riaz said. “It’s part of the daily conversation which makes it less compartmentalized and more fluid throughout the entire day.”

Professional development this summer aimed to ensure the teachers have the skillset to address the emotional needs of students this year, Riaz said. She said teachers can also refer students to a social worker if needed. Each of the system’s 14 Newark schools have two to four social workers.

León has also said the district is committed to prioritizing the social and emotional needs of students this upcoming year. During a Board of Education retreat on Saturday, he said school administrators underwent professional development over the summer that focused on social and emotional learning.

‘Spirit loss’

In Newark, 1,021 people have died from COVID, accounting for nearly half of all deaths from the virus in Essex County alone, according to county data. There were 80 new positive cases reported on Friday. The vaccination rate in the city was 45% as of Aug. 20, up from 43% a month ago, according to the state vaccination dashboard.

In a recent nationwide survey, roughly 80 percent of parents had some level of concern about their child’s mental health or social and emotional health and development since the pandemic began. Black and Hispanic parents are seven to nine percentage points more likely than white parents to report higher levels of concern, the survey reported.

“Unaddressed mental-health challenges will likely have a knock-on effect on academics going forward as well,” read the McKinsey and Company report. “Research shows that trauma and other mental-health issues can influence children’s attendance, their ability to complete schoolwork in and out of class, and even the way they learn.”

Because Newark was one of the hardest hit by the coronavirus in terms of deaths and positive rates, “it’s so much more likely that the kids in Newark have experienced some negative consequences of COVID,” Elias said.

“The challenge is that people are worried about learning loss and I think that’s a misplaced concern right now because I think we have to be concerned about spirit loss,” he added.

Riaz said teachers will find opportunities for breaks between academic lessons to teach mindfulness activities such as breathing exercises and yoga poses.

“This is not business as usual or as it was before,” she said.

Yun Shin, the early childhood division director at La Casa de Don Pedro, a community-based social service organization based in Newark, said her teachers are preparing to start with teaching 3- and 4-year-old students about the basics of mask-wearing and procedures with hand washing and hand sanitizing.

“We will talk about it, ask questions and share feelings,” said Shin, who runs the organization’s Head Start, Early Head Start, and district preschool programs. “Our teachers not only get training on how to address mental health needs, but also recognizing child abuse and other trauma.”

‘It’s Friday’

After sharing their feelings during the morning check-in, the group of teachers in the professional development session began clapping to a song Fils-Aime, the school leader, said was her favorite Friday tradition.

For this one, they took turns sharing their weekend plans. The mask-wearing teachers, whose smiles came through their eyes, chanted together in an upbeat tune:

“It’s Friday!

It’s Friday!

It’s the end of the week!

It’s Friday!

So what you gonna do?”

“I’m gonna get my nails done!” Fils-Aime sang.

“She’s gonna get her nails done all weekend long!” they sang in unison, before repeating the refrain for the next educator. This year, the teachers plan to make the sing-along a part of their Friday classroom routines.