Thousands of students with the most complex disabilities, as well as pre-K students of all abilities, began returning to their school buildings on Monday — marking a major milestone in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s push to reopen the country’s largest school system.

It’s a significant moment, as remote learning has proved especially challenging for many students with disabilities, and is a test of de Blasio’s reopening strategy, which has seen significant pushback and two delays.

“The first couple months of school closures and the quarantine were pretty awful,” said Lori Podvesker, a parent of a student with a disability and a policy expert at INCLUDEnyc, an advocacy group that focuses on special education. “Remote learning doesn’t work well for a lot of kids, but it doesn’t work well for most of our kids and especially kids with developmental disabilities.”

Podvesker’s 17-year-old son Jack returned to his school on Monday, after months of being cooped up at home. Jack, who has an intellectual disability and cerebral palsy, has become more independent and able to occupy himself since the quarantine started. But he has also lost the ability to write his own name and doesn’t want to do any reading during remote learning.

“He was so dysregulated — his environment had changed and we were locked inside basically,” Podvesker said. “Every day for the last six months he would ask when he’s going back.” So this morning, Podvesker rode with him in an Uber from Downtown Brooklyn to his Lower East Side school, a commute the pair will from now on take on public transportation while the city works out any kinks with its yellow bus service, which has typically sputtered at the beginning of the school year. When she picked him up this afternoon, Jack was “happy and tired,” Podvesker reported.

Other families of students with significant needs were less eager to return to school, despite the challenges of remote learning. Roughly 43% of students so far have opted to stay home from their District 75 schools, most of which are alternating are one week on for students and one week off. That was just shy of the citywide average for remote learners. Most of the city’s 1 million district school students will be allowed to return to school buildings next week for one to three days a week.

Bronx mom Beatrice Ayertey has three children on the autism spectrum in District 75 and another child in pre-K. Ayertey worked frantically Monday morning to make sure her children were logging on to complete assignments, a task complicated by usernames that have changed since last spring, technical issues with the iPads she received from the city, and an internet connection that falters when too many people are using it.

She has yet to hear from some of her children’s therapists, who provide services such as occupational therapy, though city officials said parents should hear from them this week to set up appointments.

“It is a bit difficult for me because you have four kids doing remote in different sections and different times during the day,” Ayertey said, noting that her 16-year-old son is the only one of her children who is able to complete his work independently.

Ayertey took a three-month leave from her job as a nurse at a local hospital to help manage her children’s fully remote learning. But despite those challenges, she is nervous about sending her children back to school because they have asthma and live with her 80-year-old mother.

“I would rather let them be here where I can manage and control their sickness,” she said. “I’m asking myself what happens in three months.”

Reopening school buildings to students coincided with a protest Monday afternoon at which some educators said it was not yet safe to return and the city has not done enough to assure students and staff will be safe.

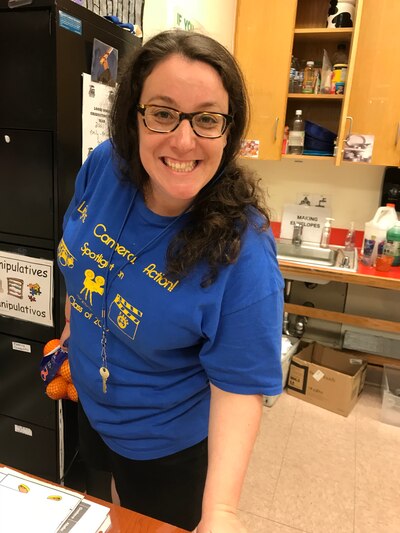

Multiple staff members at District 75 sites said they share some of those concerns, but largely felt the first day back went well. Rachael Goeler, who teaches vocational skills at a District 75 site located at Metropolitan High School in Queens, said she was “excited and apprehensive” about teaching students in person.

Some of her routines were altered. Goeler’s normal classroom is being used as furniture storage because it does not have adequate ventilation, so she taught from a different room with windows that open. The school used tape to mark off squares on the floor around students’ desks to mark six feet of distance, so if students needed to get up and stretch there would be a reminder not to leave your square. And students’ supplies were pre-sorted into paper bags so they wouldn’t have to leave their chairs to find glue, paper, scissors or pencils.

“It felt really good to see them and to see how well they were doing and to see the smiles and to see they were excited to be back in the building,” Goeler said, adding that students mostly kept their masks on, except when they were allowed to take them off during an “instructional lunch” where Goeler helped teach a lesson about hygiene. “I feel like I’m already establishing a routine that feels really good,” she said, though “I don’t know that the apprehension is going to go away anytime soon.”

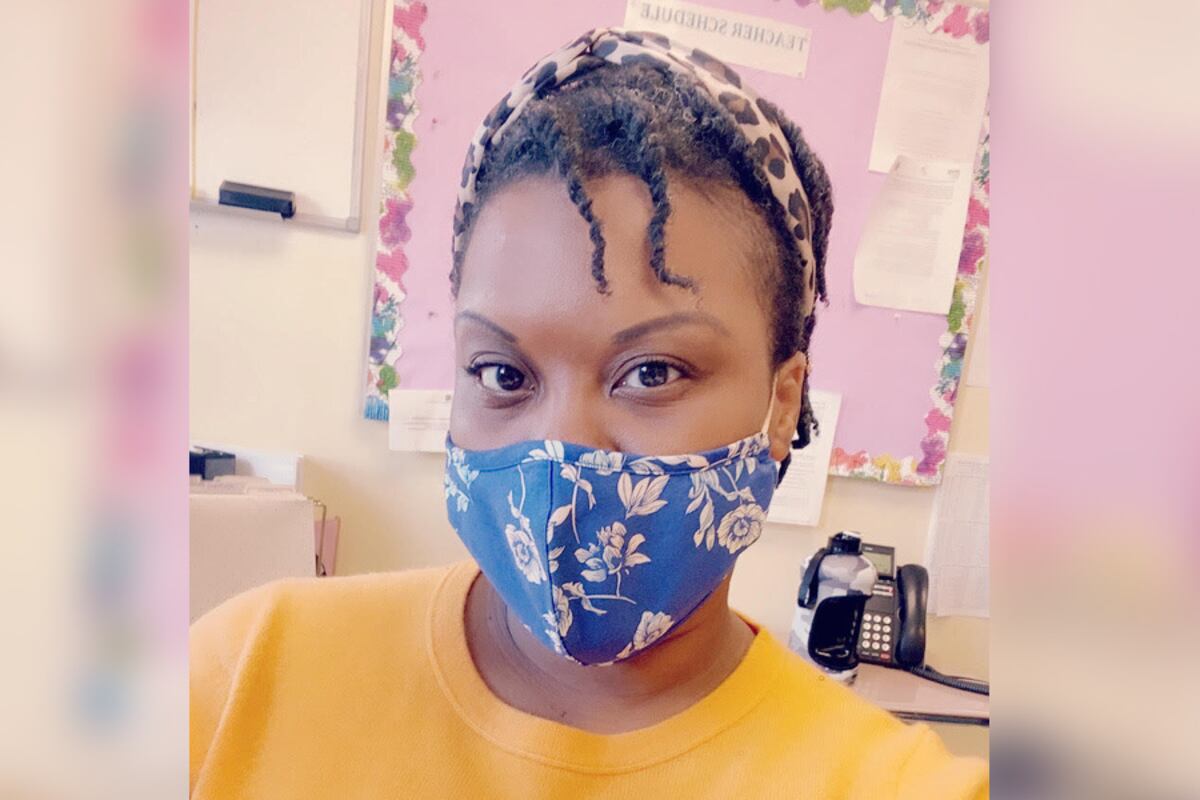

At one middle school District 75 site in South Ozone Park, Queens, only one student consistently wore a mask. But it was a manageable issue, as just five students attended in person on Monday, said Leona Fowler, an instructional support teacher at the school. She said there was plenty of personal protective equipment, such as face shields, masks, and gloves, on hand. Such protective gear is a necessity at the school, since some students need help with feeding and toileting.

Now that students are in the building, Fowler said she’s trying to help navigate a slew of instructional questions, including how to reach students who benefit from lots of hands-on learning while maintaining social distance and not relying too heavily on screens as a replacement.

“We don’t want them to be stuck to the iPad and learning virtually but in school,” Fowler said. “We’re still navigating that.”