Before this month, Isaac P. had not been inside of a classroom since March 2020, when the coronavirus forced school buildings to close across the city.

So the rising fifth-grader felt a little tense about the city’s summer program.

He had never attended summer school before this year, and on top of that, he hadn’t interacted with other students or teachers in person for more than a year. But he wanted to “learn more,” so he signed up, he said.

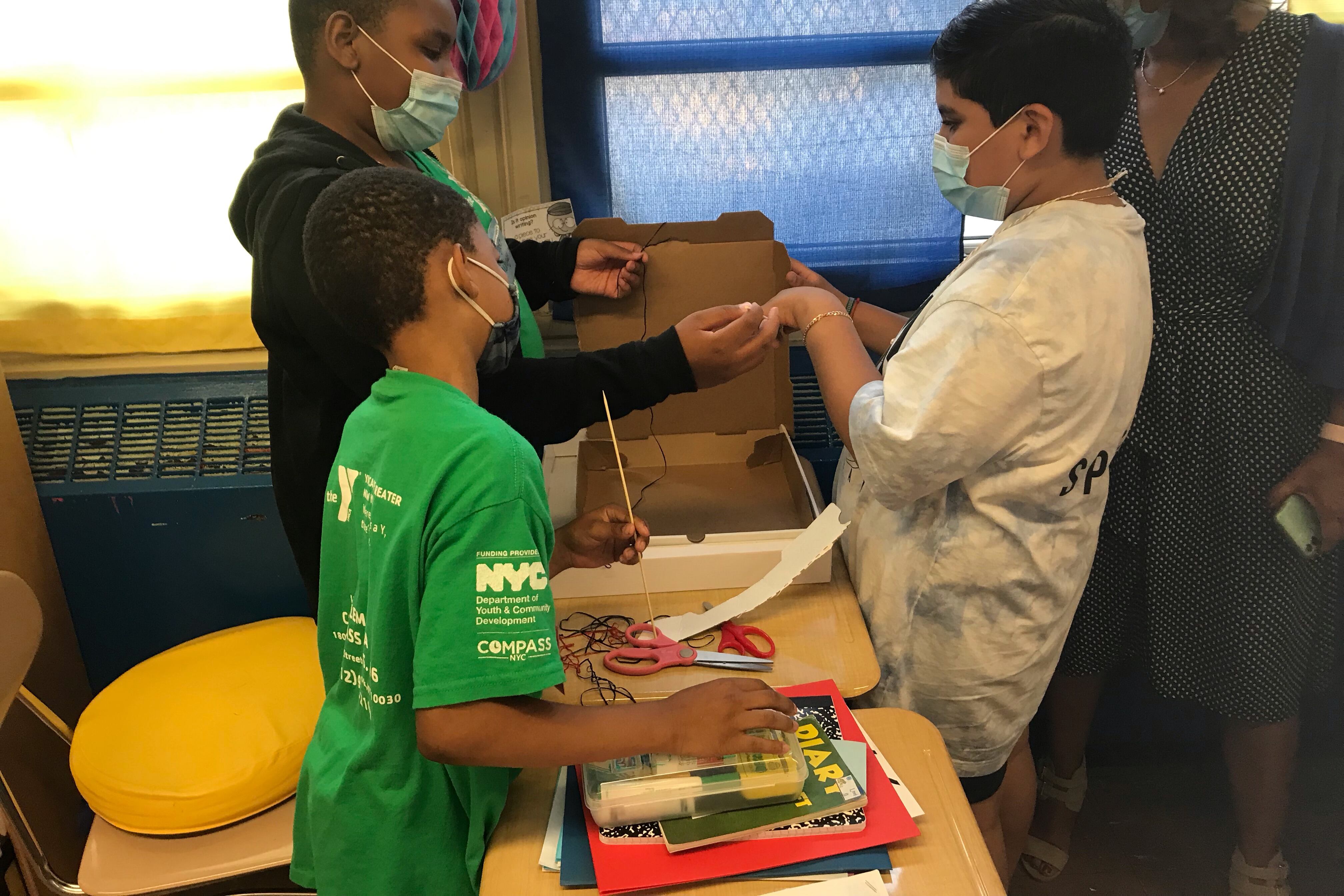

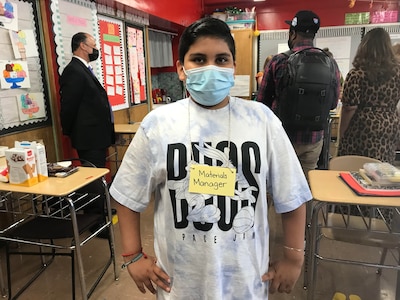

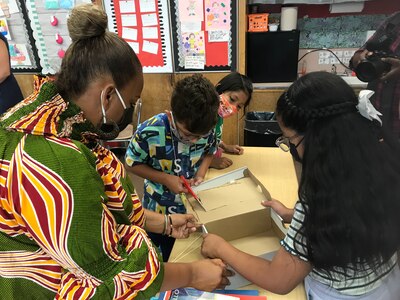

Now a few weeks in, he said his butterflies are gone. On Thursday at P.S. 96 in East Harlem, Isaac served as the “materials manager” for a STEM project, where he helped his classmates find cardboard, aluminum foil and other materials to build solar-powered ovens to cook s’mores.

“I love this,” Isaac said of the project incorporating science, technology, engineering and math.

Schools Chancellor Meisha Porter wanted the city’s ambitious Summer Rising program to be a bridge to the regular school year for children like Isaac, who is among the 200,000 students enrolled in the ambitious effort. City officials revamped summer school this year by opening it up to all students — not just those who are failing or falling behind in coursework — and offering a mix of academics and enrichment activities, provided by community-based organizations who partner with schools.

For some, summer school has traditionally carried a stigma of being for children who had fallen behind. But by opening the program to every student and adding activities, this year’s model attempts to break new ground as many students emerge from isolation to get reacquainted with their school communities.

The idea was widely lauded, but the rollout was rocky.

Many families were initially confused about how to enroll. Meanwhile schools received last-minute orders from the education department to enroll anyone who wanted to participate. As a result, some sites enrolled more children than they expected, some had trouble hiring enough staff to supervise the program. Separately, there have been concerns over transportation options for students with disabilities and those in temporary housing.

Those problems did not seem to affect P.S 96, according to Principal James Konstantinakos.

The rollout was smooth at his Harlem school, which Porter visited on Thursday. Konstantinakos said he had no issues shoring up enough staff to run it. He credited YMCA and Mission Society, the organizations that partner with his school, for doing a lot of early outreach to families ahead of the program’s launch.

When launching the program, Mayor Bill de Blasio said he hoped it would be replicated in the future. This year’s program is estimated to cost about $200 million — a “vast majority” covered by federal coronavirus relief dollars, according to education department officials. That raises questions about where this sort of funding would come from down the line, when this dedicated federal funding runs out.

When Porter visited P.S. 96, which enrolled about 120 children this summer, she looked at the solar ovens and turned to Isaac, who greeted her at the door: “[Is] this literally gonna cook s’mores?” He nodded yes — and showed her all their supplies, including marshmallows, graham crackers, and chocolate.

As Isaac zipped around the room to help his classmates, students cut out the tops of cardboard boxes and attached aluminum foil to the top so that they could capture heat from the sun. Porter joined in, holding one group’s cardboard box as a student used scissors to cut the top.

(A Chalkbeat reporter did not stick around long enough to see whether the marshmallows melted onto the graham crackers.)

This was the sort of in-person experience that Isaac had missed for the past 16 months. But he was most excited about silent reading time, after which students must write down a summary of the chapter they read. He’s on Chapter 11 of “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.”

Isaac didn’t opt for in-person learning this year — just like three out of every five New York City students — because of fears about contracting the coronavirus.

Isaac said he’s looking forward to the fall because he will “get to see my friends again,” and he’ll have recess. For months, he had been nervous about what it would be like since it had been so long since he’d stepped inside of a school. After attending summer school for a few weeks, it seems that some of those nerves are starting to wear off.

“I’m feeling a bit more confident, a bit nervous at the same time,” Isaac said.