Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter How I Teach to get inspiration, news, and advice for — and from — educators.

High school math teacher Larisa Bukalov came to the U.S. with her family 30 years ago as a refugee from Ukraine, when it was part of the Soviet Union. She was 19 at the time.

In the eyes of many New Yorkers, she was Russian, which was her first language. How she viewed herself, however, changed when Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022.

“The words can’t describe the pain and anxiety I experienced when the first tanks started advancing to Kyiv,” said Bukalov, who’s been teaching at Bayside High School in Queens for 25 years. “On that day, my identity changed from Russian emigrant to Ukrainian American.”

Remembering how her own childhood was filled with math competitions that pushed her to feel challenged and engaged, she wrote to the Mathematical Association of America, asking if she could organize the American Mathematics Competition in Ukraine, since that nation’s local and regional competitions had been canceled. To Bukalov’s surprise, the math organization agreed to her plan. Bukalov assumed the role as the association’s liaison to Ukraine.

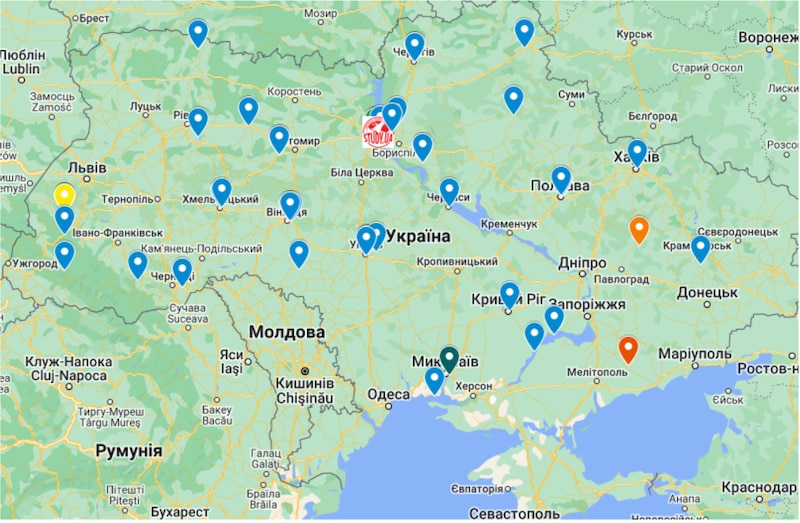

The organization Tutoring Without Borders helped her advertise the contest and recruit students. She used social media to find kids and teachers and fundraised to pay the competition fees and contest translations. In the end, 196 Ukrainian students signed up, though only 152 competed because of lack of heat and electricity and internet interruptions, Bukalov said. Roughly 30 of the participating students were Ukrainian students who had fled the country and were living abroad, including four living in the U.S. (Bukalov helped get them permission to take the exam in Ukrainian.)

Bukalov, who has taught everything from pre-algebra to multivariable calculus, is being recognized this month by Math for America, receiving the organization’s prestigious Muller Award for Professional Influence in Education for her commitment to developing current and future mathematics teachers through mentoring, writing textbooks, and designing professional learning experiences.

She joined Math for America more than 15 years ago, around the time she considered getting a doctorate in math education. The organization, which builds a community for exceptional math and science teachers, offered her a different solution: to stay in the classroom and practice her craft while mentoring teachers and creating professional development workshops.

Now, Bukalov is trying to start an organization based on the Math for America model in Ukraine. She spoke recently with Chalkbeat.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How and when did you decide to become a teacher?

I was raised by my maternal grandparents who were teachers. You can say that I grew up in a school. By the end of eighth grade, I firmly believed that I wanted to teach math. There were a few reasons for it:

• I entered high school at the end of the Soviet era and Perestroika. My classmates constantly harassed our government and history teacher about her brainwashing and lying to her students for years. Did she really believe in what she was teaching? I did not want to wear her shoes.

• As I learned more advanced mathematics, I loved it more and more. I used to spend hours and sometimes days on a particularly interesting problem until, finally, I would come up with a solution.

• Probably the most important reason was my grandfather. As I got older, I understood that my grandfather was a brilliant mathematician. He also was not just a math teacher in a rural Ukrainian school. He trained teachers, lectured in a local teacher college, wrote articles, and presented at conferences. I wanted to emulate him in everything he did.

Tell us more about your role as the Mathematical Association of America’s liaison to Ukraine.

While working on the contest, I often heard that ‘we have to save the best Ukrainian kids.’ That really bothered me. As an educator, I was thinking about the struggling students. Who is helping them?

Around that time, I saw a picture of a Ukrainian math teacher sitting in a gas station and teaching his class remotely. I wondered how many of my colleagues would do the same. I started working with Ukrainian math teachers. Together with [math education researcher] Daryna Vasilieva, we started a Telegram group for math teachers. [Telegram is a messaging and audio platform similar to WhatsApp.]

We organized workshops supporting Ukrainian school reform, New Ukrainian School, and opened space for teachers to showcase their work, share concerns, and collaboratively plan. Now our dream is to build a community similar to the Math for America model.

Are there ways the Russian invasion of Ukraine has affected your students here in NYC? Did your students do the math contest with the students from Ukraine?

In the U.S., any student is invited to the first round. In New York City, large non-specialized high schools like Bayside, Cardozo, Francis Lewis, and Midwood sign up to participate in the American mathematics competition. All specialized high schools participate. In the U.S., the top 5% of participants get invited to the next level; 11% of Ukrainian kids received qualifying scores.

My math team students wanted to know how the kids in Ukraine scored relative to them. They compared their solutions and exchanged challenge problems.

During the competition season, my department and school administration were also very supportive. Teachers volunteered to proctor the exams, generously donated money, and frequently just asked how the kids were doing.

This experience also opened a space for my students to share their family histories and talk about struggles their families had as new immigrants. The war in Ukraine became real, not just an item from the list of current events. In math we seldom get an opportunity to talk about democracy, identity, and justice. This year kids were a lot more open.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach and why?

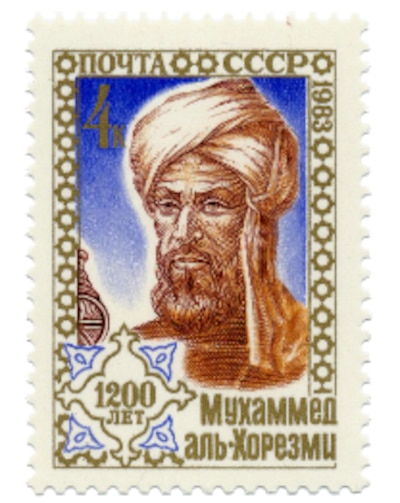

Anything that can be taught using textile or visual experiences, like manipulatives or illustrations. For example, the area model. We first find the area model in the writing of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who is considered the father of modern algebra.

This model illustrates operations with numbers and polynomials and helps students to build an intuitive understanding of algebra without memorizing long and meaningless preceders. (I can’t memorize!) Teachers who use this model are building a bridge between basic arithmetics and sophisticated algebraic computations used in advanced mathematics. Their students are more likely to see a big and connected system instead of a disjointed list of steps and procedures. This model also presents an opportunity to discuss non-European origins of modern algebra.

Kids love to know who thought of this stuff!

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

Remember that I attended school in the USSR.

I was very lucky to have many outstanding teachers. For example, My first to third grade teacher received the national teaching award. In the early 1980s, she had an overhead projector, used homemade manipulatives, frequently used group work, and took on student teachers.

My Ukrainian language and literature teacher was the most kind and sweet person. I could sit for hours and listen to her speak Ukrainian. It is very melodic. I always loved reading, but after meeting her, I became obsessed with Ukrainian poetry, folk music and dance, and ethnic costumes. My dolls were the best dressed because I used to make outfits for them based on the pictures of historic Ukrainian garments I researched in the library.

What new issues arose at your school or in your classroom during the 2022-23 school year, and how did you address them?

Mental health is still the big one after we came back to school from fully remote instruction. In each of my classes, at least one student was out of school for an extended period of time, more than two weeks, due to mental health illness. This is significantly more compared to pre-COVID. In Bayside, the caseload of each guidance counselor was reduced to 250 students, and additional social workers were hired. Teachers are very alert to changes in students’ moods and attendance. We try our best. Parents often complain to us that they can’t get services for their children outside the school because most of the providers do not take their insurance and only accept out-of-pocket payments.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received, and how have you put it into practice?

After teaching for a few months, I lost my voice. My grandfather, as a teacher trainer, diagnosed my illness: “You are talking too much! Your job is to facilitate the conversation in your classroom, not to talk at your students.” This affected my teaching in two ways. I stopped talking at my students and concentrated more on creating lessons where my students can do most of the thinking and explaining.

Additionally, I learned that when things in the classroom do not work out the way I planned, I need to examine my own teaching practices and see what needs to be changed. Blaming parents, elementary school teachers, or anyone else is not productive. However, reflecting on your own teaching practices is a constructive way to grow professionally.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.