Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

Clasping a deck of pale yellow flash cards, Sloan Shapiro delivered a phonics lesson she’s taught countless times at her Manhattan private school for children with reading challenges.

“Q — U — Queen — Kwuh,” Shapiro chanted, pointing at the letters “Qu” printed on a card above a cartoon drawing of a queen. A chorus of students mimicked her sounds, tracing invisible letters on their hands.

Without missing a beat, Shapiro ticked off a spelling rule. “Q is always followed by a…”

“U!” the group responded in unison.

The chorus of students responding to Shapiro on a recent Monday afternoon at the Stephen Gaynor School, however, weren’t children. They were teachers from P.S. 84, an Upper West Side public school around the corner.

For the first time, Gaynor is offering a free 15-week course to nine public school educators to help refine their lessons on phonics, which explicitly teaches the relationship between sounds and letters. The small pilot program comes as elementary schools across the city are under a new mandate to emphasize phonics, part of a sweeping plan to overhaul the way New York City public schools teach reading.

Schools Chancellor David Banks has embraced partnerships with private schools that cater to students with reading challenges, though an Education Department spokesperson could not say how prevalent such arrangements are. Banks has also expressed interest in improving public programs to reduce the ballooning costs associated with paying for private school tuition. About 80% of families at Gaynor, which charges nearly $80,000 a year, seek tuition payments from the government, arguing the public schools can’t adequately educate their children.

For the past 17 years, Gaynor has partnered with P.S. 84 and nearby P.S. 166, offering free after-school help for about two dozen students each year who are behind in reading. But it didn’t make sense previously to directly train their teachers because the public schools’ approach to literacy was so different, according to head of school Scott Gaynor, who is the grandson of the school’s co-founder.

P.S. 84 has long deployed “Units of Study,” a curriculum created by Teachers College Professor Lucy Calkins. That program, which has been used by hundreds of city elementary schools in recent years, has been criticized by experts in part because it does not include as much emphasis on phonics. With the city’s new phonics push and curriculum mandate, schools are no longer allowed to use Calkins’ program, and Gaynor is considering expanding their training efforts to schools beyond P.S. 84.

But even as the city moves away from Calkins’ approach, that’s only a first step.

“The harder part of the equation is the training,” Gaynor said. “That doesn’t happen from a one-day or even a one-week workshop.”

Going deeper than previous phonics trainings

Teachers at P.S. 84 said their own experiences with phonics training have been mixed.

“We have been through many different [phonics] programs, so it was a little bit all over the place,” said Johana Talbot, a first grade teacher who said she appreciated the training program at Gaynor. (The principal of P.S. 84 declined an interview request.)

The pilot program at Gaynor involves 45 minutes a week of training in a method called Orton-Gillingham that has historically been used for children with dyslexia, but is increasingly deployed with a wider range of students.

That approach is designed to break down the building blocks of language, teaching children basic spelling rules and sound-letter relationships, building in complexity over time. It also incorporates sight, touch, and movement to help make the ideas stick. Students may tap their fingers as they sound out words or move their arms to represent certain sounds.

Though officials at Gaynor said the approach has worked for their students, the evidence of Orton-Gillingham’s effectiveness more broadly is limited.

Talbot has practiced some of the lessons she’s learned at Gaynor in her classroom at P.S. 84. She encouraged students to tap out sounds with their non-dominant hand instead of their dominant hand, a small tweak that helps them use that strategy during writing exercises.

“The movements for every sound [and] chanting the rules — they feel very empowered by that,” said Talbot. About 10 of her students are recent migrants and some of them have proudly shown off some of those strategies with their parents.

P.S. 84′s Carla Murray-Bolling moved this year from preschool to kindergarten, where she is teaching phonics for the first time. “I was basically just thrown in and told: ‘swim.’”

One practice she’s learned is how to encourage students to blend different sounds of a word together. “It’s been helping them by dragging the sounds out instead of breaking them down one letter at a time,” she said.

For Shapiro and her co-teacher, Kristi Evans, the goal is to help teachers understand the reading principles behind the lessons and determine whether students have actually mastered them.

“If you teach teachers the underlying structure of the language, they can really pick up anything,” Shapiro said.

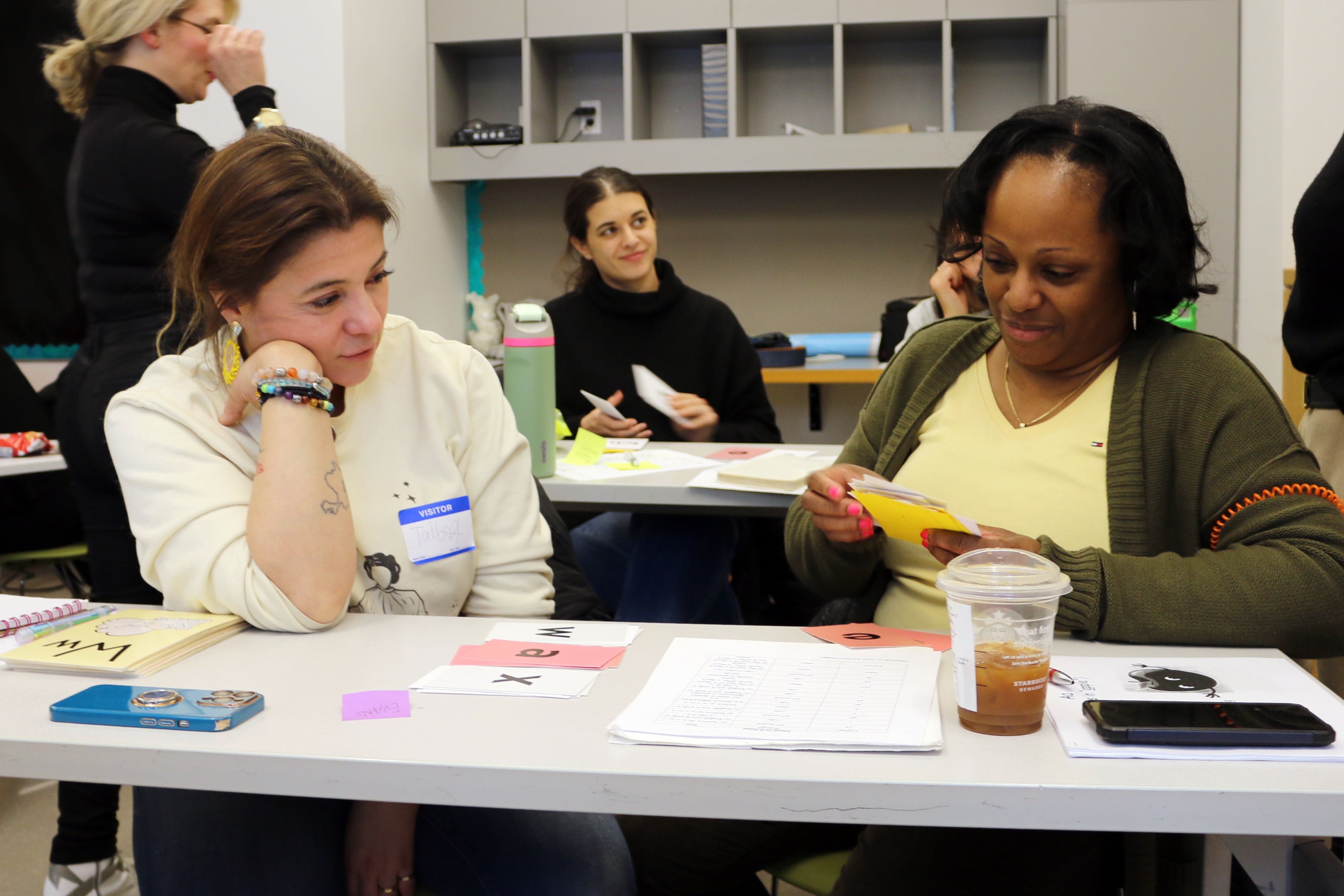

During a recent training session, Murray-Bolling and Talbot paired up to practice testing each other on “nonsense” words that still follow normal spelling rules, giggling as they teased each other with words like “jetch.”

Students who struggle with reading often develop strategies to compensate by using context clues and pictures, Evans said. That often helps them advance to higher grade levels even if they’re behind in reading. By presenting nonsense words, Murray-Bolling and Talbot were learning a quick assessment to help identify whether any of their students had come up with ways to correctly guess a word’s meaning.

“We get those students,” Evans said, referring to students who enroll at Gaynor. “We’re hoping that in the public school we can catch those kids earlier.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.