Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter How I Teach to get inspiration, news, and advice for — and from — educators.

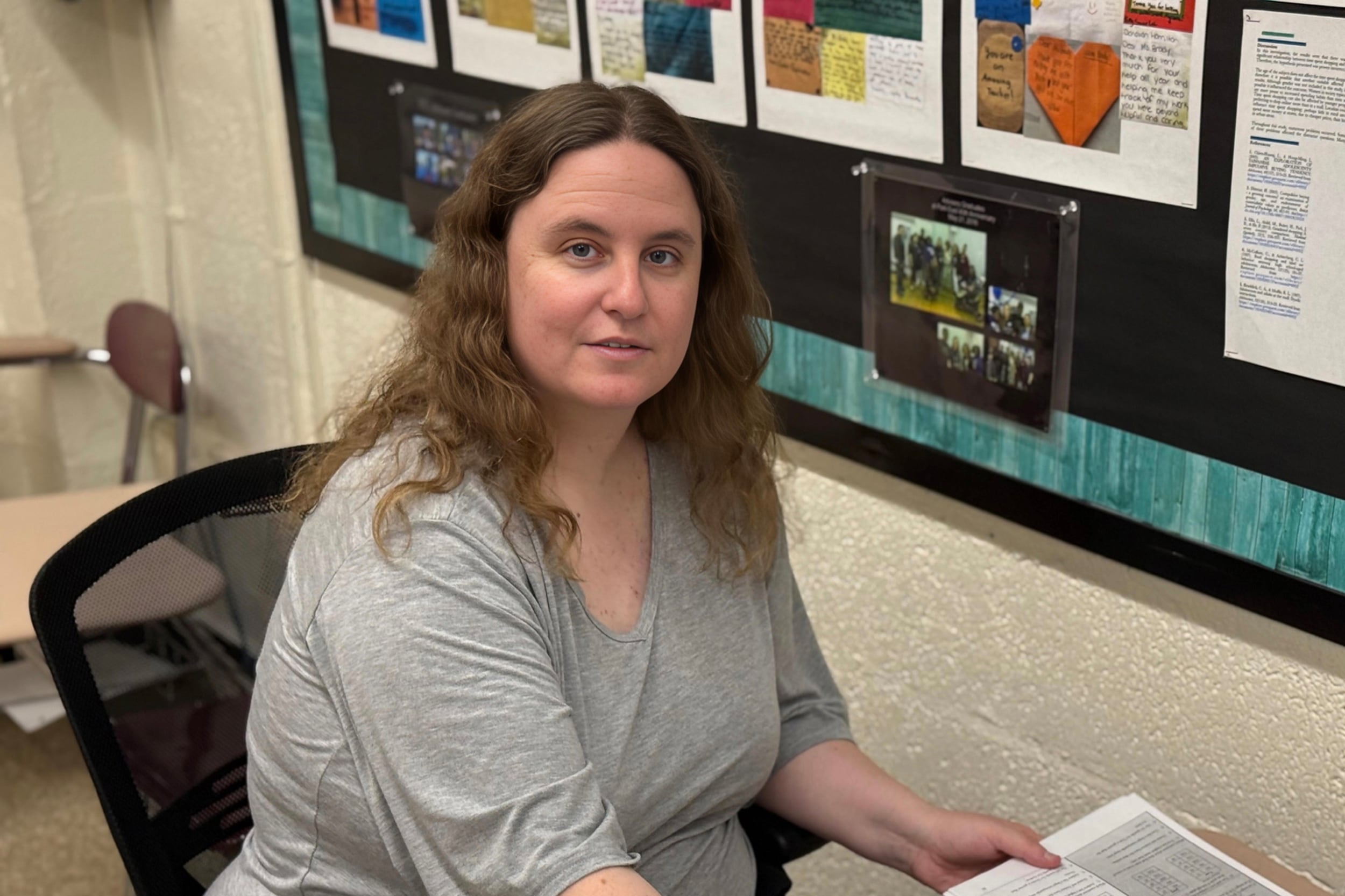

Park East High School was deemed a “School In Need of Improvement” on a state list and in danger of closing when Lauren Brady started teaching math there 20 years ago.

Among the reasons the state flagged the school: its abysmal math Regents scores.

Brady accepted the challenge, eyes wide open, and immediately dug into the data.

Brady suggested trying something different — small group instruction for students at risk of failing. She piloted the program, refining it over time. Those efforts resulted in a 100% passing rate.

Two decades later, Brady’s approach continues to produce strong results, and Park East High School, in Manhattan’s East Harlem, is no longer threatened with closure. Brady, who teaches small group instruction for ninth grade algebra as well as 12th grade statistics, was recently recognized by Math for America with the prestigious Muller Award for Professional Influence in Education, which comes with $20,000 in prize money for the winning teacher and $5,000 for their school.

Brady is a highly decorated educator. She won a 2014 Sloan Award for Excellence in Teaching Mathematics, is a master teacher through the NYC Teacher Career Pathways, and is a four-time Math for America master teacher. Brady’s statistics lessons have been published by the U.S. Census Bureau, her teaching strategies appear in a book by the educator Doug Lemov, and she’s also an accomplished spoken word poet.

She credits her own teaching style to her favorite math teacher from high school, Ms. Young, for whom Brady acted as a “teaching assistant.” Ms. Young advised Brady to teach through questioning instead of directly telling students how to solve problems.

“During small group instruction, questions are practically my only form of communication,” Brady said. “I radically embraced this strategy, which has profoundly impacted my instructional approach.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How and when did you decide to become a teacher?

At 14, I penned a plan to teach ninth-grade math in Harlem. Early experiences like tutoring for Athletes Helping Athletes, under Mr. Rosen, reinforced teaching was the right fit. At 16, I started a tutoring business; guidance counselors referred students preparing to retake Regents exams. During college, I participated in community research on high school dropout rates and taught an adult GED course.

I wavered between [studying] psychology and teaching math, and enrolled in NYU’s Psychology Ph.D. program. It took all of six days to realize I was more invested in my teaching assistantship lecturing graduate statistics than in my psychology research and coursework.

I immediately withdrew and, per my plan from age 14, started teaching ninth-grade math in Harlem in the middle of the school year. Twenty years later, I’m still at the same school: Park East High School.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach and why?

I love teaching election decision methods in statistics. Students are presented with a set of completed ranked-choice ballots and asked who they think should be elected. Many rationales emerge from ‘the one with the most first-place votes’ to ‘the least hated.’ We examine various election decision methods (e.g., plurality, types of run-offs, Borda count, Condorcet) and determine who would win using each. It turns out a different winner emerges with each election decision method, raising larger questions about how to count ballots.

A gerrymandering lesson in the same unit is also a favorite. Students draw boundaries to create districts in a hypothetical region. They’re shocked when they discover how to rig the party with less votes overall to win the majority of the districts. What I love about these lessons is they bring together concepts and procedures in a real-world context.

I know you’ve talked about how math acts as a gatekeeper at two critical times: with having to complete Algebra I by ninth grade to take upper-level math courses, and requiring college math courses for some post-secondary degrees. Can you tell me a bit about how you’re addressing these issues in your classroom?

The majority of Algebra I students at my school enter below grade level, so we invest in small group instruction. Ninety-eight to 100% consistently pass the Algebra I course and Regents by ninth grade, ensuring three years of upper-level math.

The small group instruction model is really quite simple and works if a few core elements are in place. At-risk students (identified by data) are pulled from math class twice a week in groups of four. They solve the same problems as the larger class, but with oral questioning and prompts tailored to the needs of each individual. It’s really a tutoring model: one teacher with four students.

Seniors at Park East are given a choice, with guidance based on career goals, of statistics, pre-calculus, or calculus. I find it tough to prepare my statistics students for core curriculum requirements in college. I encourage them to reflect on their mathematical strengths in considering whether to satisfy core requirements via algebra- or statistics-based pathways. We talk about how some colleges may automatically enroll them in algebra, so they should self-advocate if they prefer statistics. And we address how some colleges, unfortunately, won’t offer a choice at all. I spoke at Critical Issues in Mathematics Education [an annual workshop series] on this issue, as the work here is really to advocate for colleges to expand options.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom or your school?

For over a decade, my statistics students have been writing letters to the U.S. Census Bureau, advocating for changes to the race and ethnic origin questions. Once, the Census Bureau’s Associate Director and chief of the Racial Statistics Branch responded in person with a visit to my classes. Finally, in 2020, the Census Bureau addressed my students’ most significant complaint: “Negro” was removed as an answer choice. They continue to advocate for revisions, such as a combined race and ethnic origin question and the option to identify with more than one ethnicity.

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

I began kindergarten in the Malverne [Long Island] school district 22 years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke there and led a march in support of its desegregation. It was the first school district in New York to be given a state-level desegregation order, which was upheld after multiple appeals, including a challenge to the U.S. Supreme Court. I received an excellent K-12 education there, both with respect to academics and community. The experience also compelled me to grapple with systemic racial bias in education and face my own privilege. It instilled a value of racial equity in education, which influenced my decision to teach public school in New York City and to serve on the equity teams at my school and Math for America.

I also attended New College of Florida, a tiny, unconventional school that championed student choice and innovation. Classes were small and rigorous. Students regularly initiated independent study and conducted original research. And there were no required core classes or grades. This unique experience influenced me to value intrinsic motivation and create space for students to conduct original research in my statistics course. Unfortunately, the educational freedoms signature to New College are being dismantled. I hope they will be restored one day.

What are some of your hobbies, and how do you relate them to the classroom?

A hobby of mine is spoken word poetry. I was a member of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe’s National Slam Team. My work has appeared in an international film festival, an Off-Broadway play, and a motion picture. At Math for America, I facilitate a writing workshop for STEM teachers. I also taught a poetry elective at my school. Students generated writing and audio recordings, plus spoken word poets performed live for the class each week. After school, I hosted schoolwide open mics and brought some students to record tracks in the studio.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy atazimmer@chalkbeat.org.