Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

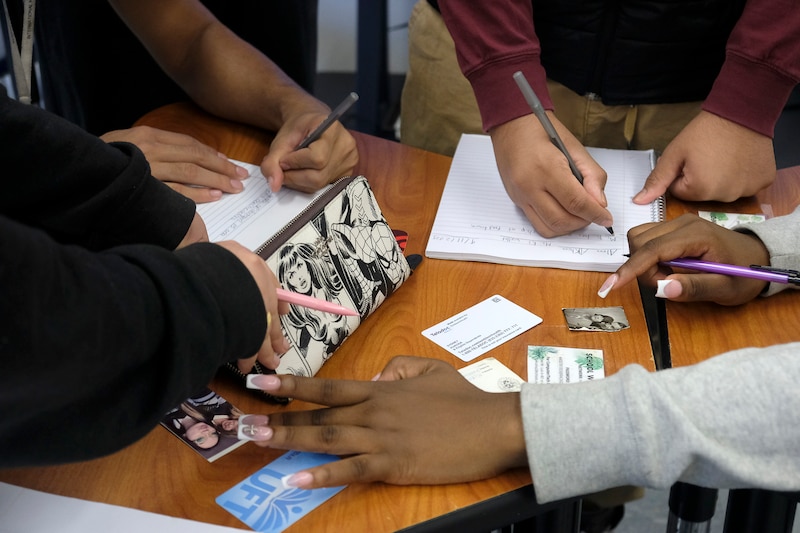

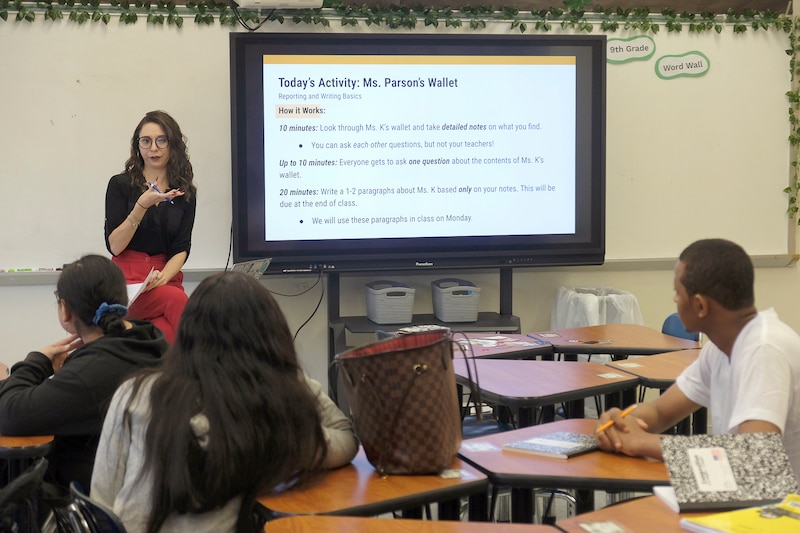

Brooklyn English teacher Sydney Kukoda launched her new journalism elective class last week with an unconventional assignment. She emptied the contents of her wallet onto a desk and asked her students to investigate, take notes, and then write a short biography of her based on facts they had independently verified.

A worn business card from a Parisian restaurant caught the attention of Ibrahima Diallo, a 17-year-old junior from Guinea.

“Did you work at the French restaurant?” asked Ibrahima, who is part of the school’s growing community of English language learners.

Kukoda said she didn’t.

“How long have you been shopping at Costco?” another student asked, after spotting a membership card.

“I’ve been going to Costco with my family since I was a kid,” Kukoda said. “And I was able to get my own Costco card on my family’s account when I was 18.”

The lesson was part of a new curriculum launched this year at the High School for Global Citizenship through Journalism for All, an initiative aimed at expanding access and equity in youth journalism in New York City’s public high schools.

Just 1% — or nearly 3,220 — of roughly 290,000 public high school students had access to some type of journalism course last year, according to an inaugural report from the New York City Department of Education, released Monday. The report, based on self-reported school data, showed the students were spread across 90 of the city’s roughly 400 public high schools. (The report also included a list of 35 high schools that had print or online student newspapers, but that tally appeared to be incomplete. The coalition has a “newsstand” website with links to about 90 student publications across the city.)

The report comes following advocacy by the Youth Journalism Coalition, a project of the youth journalism nonprofit The Bell. (The Bell partners with Chalkbeat on the P.S. Weekly podcast.) Last year, the coalition pushed the New York City Council to pass Local Law 27, which requires the chancellor to publish an annual report on journalism programming in New York City high schools.

“At the end of the day, we need to see that number go up,” Youth Journalism Coalition Director CJ Sánchez said about the education department’s data.

Hundreds of students and teachers from the coalition were expected to rally on Tuesday on the steps of City Hall to celebrate their effort to increase access to journalism education and call for increased city investment in it.

Schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos has expressed support for expanding access to student journalism.

“Through their reporting, our young people develop critical thinking skills, learn to advocate for their communities, and drive meaningful conversations about the issues that matter most to them,” she said in a statement. “I encourage all our school communities to value, support, and amplify student voices as they continue to push important conversations forward.”

Expanding access to journalism education

As part of the coalition’s push to expand access to journalism education it partnered with CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism to create a curriculum and teacher training for schools that have historically lacked such programs. Called Journalism for All, they are piloting their new journalism courses in 30 public high schools across the city.

Principals of schools in the inaugural cohort requested $5,000 per year over the next three years from their local City Council members. So far, just six council members have agreed to give schools $5,000 this year toward their journalism programs. In 2024, the City Council passed a resolution calling on the New York City Department of Education to “provide support for a student newspaper at every high school.” (Resolutions are not legally binding).

At the High School for Global Citizenship, where 76% of students are Black, 16% are Latino, and 90% are economically disadvantaged, the arrival of a journalism course represents more than just a new elective. It’s an opportunity for students to express themselves, build agency, and have a say in and about what happens in their communities and in the world, Kukoda said.

Before launching the class this year through the Journalism for All initiative, Kukoda acted as an advisor to the school’s journalism club that students launched in May 2024, naming it HSGC Today. That debut issue from June 2024 featured the results of a student poll on who they thought won the Kendrick Lamar and Drake feud (Lamar won by a landslide), summer reading and activity recommendations, and coverage of the school’s sports teams.

Since then, students have reported on a wide range of topics. When a student journalist won the prestigious POSSE Scholarship and a full ride to Brandeis University in Massachusetts, another student reporter wrote a profile about her and the scholarship program. The paper’s February issue examined the national wave of book bans and the banning of AP African American Studies — a course offered at Global Citizenship — at a Florida school. Other stories have tackled gun laws and gun violence in students’ neighborhoods, as well as changes to immigration policy under the Trump administration.

“Our students are very aware of the ways in which they’re systemically disprivileged in our society, and they are very aware of their surroundings and neighborhoods. And so they take the responsibility and the opportunity of having a student voice very seriously,” said Kukoda, who oversees the paper with another teacher.

Junior Ramatou Toure wrote an explainer on Eid, a Muslim holiday that she and her family celebrate.

“I feel as though I was really represented in that way because I got to talk about it,” Ramatou, 16, said.

When the school implemented its cellphone ban policy last winter, HSGC Today published a spread featuring student responses to the policy and an interview with the school’s principal.

“It kind of marked in my eyes a shift in the newspaper where the students felt more comfortable almost challenging school norms,” Kukoda said of the cellphone policy reporting.

While the journalism club meets weekly after school for one to two hours, the new elective offers students the chance to learn journalism during a full class period, four times a week. It also expands access to the school paper, allowing more students to participate.

“We’re building a model that can be replicated across the school district and ultimately outside of New York City in any school district that is prioritizing their students, media literacy, civic engagement, and career pathways,” Sánchez said.

Increasing student engagement through journalism

Sixty schools applied to be a part of the inaugural Journalism for All cohort. The coalition prioritized applications from schools that showed buy-in from students, teachers, and principals. It also prioritized schools that were underresourced, with students who faced barriers to their education.

Sánchez said these schools have the most to gain from the creative learning approaches supported by Journalism for All, which can help students stay interested in class, build reading skills, and feel more connected to their school.

“Our idea is, if it can work here, it can work anywhere,” they said.

The coalition has enlisted a team of New York University researchers to evaluate the pilot program. It plans to share the findings with the Department of Education.

Kukoda has noticed how being part of the student paper has increased engagement in class, especially among students with disabilities or language barriers, because journalism feels more accessible than traditional academic work.

“It’s been a really beautiful and prideful journey to watch some of them grow more confident — asking tough questions, sharing their opinions,” Kukoda said.

Global Citizenship junior Yamira Galicia, 16, began contributing to the student paper last year. She is bilingual and speaks Spanish, a skill she has brought to the newspaper, which sometimes publishes stories in Spanish.

“ I think the class should be taught more in other schools because I’m pretty sure there’s a lot of other kids who love telling stories and might have a gift,” Yamira said.

Seyma Bayram is a New York City-based journalist. You can reach her at sbayram@chalkbeat.org.