Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter How I Teach to get inspiration, news, and advice for — and from — educators.

In New York, classroom educators often help create state assessments. Few however, are from New York City, like Bronx earth science teacher Carolina Castro-Skehan.

Since 2018, she has been working as an educational specialist with the New York State Department of Education, trekking to Albany to help develop the New York State Earth and Space Science Regents exams.

“The experience offers a true behind-the-scenes look at how the exams are designed and aligned to the standards,” Castro-Skehan said. “That insight is invaluable and has made me a stronger classroom teacher and a better mentor to other educators.”

But her path as an educator was not a straightforward one.

After college, Carolina Castro-Skehan worked for a New York City-based cosmetic company. It was fast-paced and even glamorous at times, she said. She used her biology and business background to understand the science behind the products and how they were marketed.

Then came the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, and her job began to feel “empty.”

She pivoted to teaching, landing 24 years ago at DeWitt Clinton High School, the same public school she attended as a student. For the past five years, Castro-Skehan has been at Comprehensive Model School Project in the South Bronx, where she is the science department chair and teaches earth science to freshmen and sophomores.

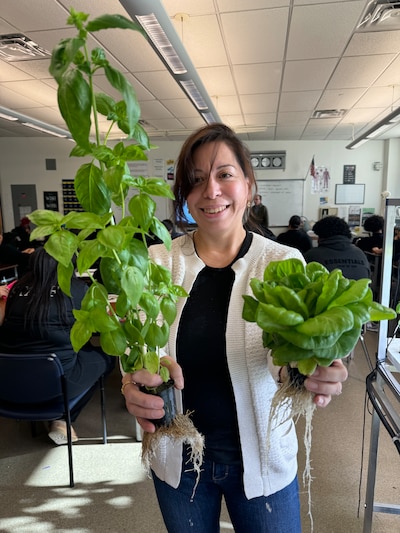

To bring earth science to life, Castro-Skehan’s students participate in real-world projects such as growing produce for the school community or local food banks through a hydroponics program with NY Sun Works. She was recently recognized by the National Association of Geoscience Teachers with an “Outstanding Earth Science Teacher”award for both New York state and the Eastern Section for her sustainability and environmental projects.

Castro-Skehan also continually seeks out professional development opportunities and fellowships taking her into the field. She’s explored the Jurassic Coast in England, studied dinosaur fossils at dig sites in Montana, and sailed on an ocean drilling ship to learn how core samples reveal Earth’s past environments.

“Staying curious and continuing to learn alongside my students,” she said, “is what keeps my teaching meaningful and my classroom a place where curiosity thrives.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach and why?

My favorite lesson is our rain garden and street tree unit, which is really our core lesson on green infrastructure. It starts with a real problem students see every day: flooding around our school.

In the classroom, students build water filters and explore porosity and permeability, seeing firsthand why some surfaces absorb water while others don’t. Then we move outside. Students study the compacted soil around our street trees, loosen it, add fresh soil and native plants, and observe how healthier ground improves infiltration after storms.

Street flooding becomes becomes a way to teach geology, hydrology, ecosystems, and community action all at once. Throughout the year, students return to the same sites, observe changes after rainfall, and use what they’ve learned to argue for greener, better-draining spaces around our school.

Tell us how you approach teaching challenging scientific concepts particularly for students who are simultaneously learning English as a new language.

Hands-on, real-world science lessons are especially important for students who are learning English as a new language. When we teach through phenomena, students don’t have to wait until they’ve mastered scientific vocabulary to participate. They can jump in right away by observing, questioning, and making sense of what they see, which isn’t limited by language.

This kind of learning also allows students to participate from the start by sharing their own lived experiences. For example, when we study hurricanes or earthquakes, many students bring in personal experiences from events like Hurricanes Maria or Sandy, or earthquakes they experienced while living in the Caribbean. They talk about how their families prepared, what worked, and what they think could have been done better. Those conversations become the foundation for learning the science behind these events.

Language develops naturally as students explain their thinking, listen to one another, and refine their ideas.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom?

The area around my school is heavily urban. We’re crisscrossed by major highways and surrounded by heavy traffic, auto repair shops, and very little green space. Air quality is poor, flooding is common, and dilapidated concrete dominates the landscape. This is the reality my students walk through every day, and it shapes not only what I teach, but how I teach.

We talk about why our neighborhood looks the way it does, including the legacy of urban planning decisions associated with people like Robert Moses, that prioritized highways and automobile access over existing communities, public transit, and quality of life, particularly in marginalized neighborhoods. From there, we focus on what can be done to make it better.

How did you start working with the NY Sun Works hydroponics program? And how has that helped your school’s community while also giving hands-on learning experiences to your students?

I first became involved with the NY Sun Works hydroponics program through my work as a Master Teacher with Math for America. During a workshop at DeWitt Clinton High School, I saw how deeply students were engaged in growing food while learning the science behind it.

They were testing systems, collecting data, and producing nutritious food for their school community. I wanted to bring that experience to my own school.

Hydroponics labs are bright, active spaces filled with water, light, and growing plants that transform a dry classroom into a living lab. If I couldn’t green the space outside our school, I thought, maybe I could do it inside a classroom. That idea became a reality in our high school, where the hydroponics lab is now one of our most popular and successful science electives.

Because of that success, I worked with the development director of NY Sun Works, Megan Nordgrén, who helped identify a grant opportunity and supported me in writing the proposal, to expand the program into our middle school. With the support of my principal, Ms. Ricci, and approval from City Council member Althea Stevens, the project was allocated $200,000 in funding. In June 2025, we received confirmation that, once the budget passes, the School Construction Authority will fully fund the construction of the new lab in partnership with NY Sun Works.

The new middle school hydroponics lab will allow students to begin this learning earlier and will be named in honor of Jacob Pimentel, a beloved student who passed away in 2024 and was one of the first participants in our high school hydroponics program.

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

When I think back on my own learning in high school, the most memorable experiences were the ones where I was given opportunities to lead my own learning with the support of a teacher. Those were the moments when I felt most engaged, challenged, and confident because I wasn’t just receiving information, I was actively making sense of it.

That experience shapes how I teach today. I try to create classrooms where students have ownership over their learning, where they’re encouraged to ask questions, investigate real problems, and take intellectual risks, knowing there’s a teacher there to guide and support them.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.