Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to reword and properly attribute phrases that appeared verbatim in a press release from the Human Rights Campaign.

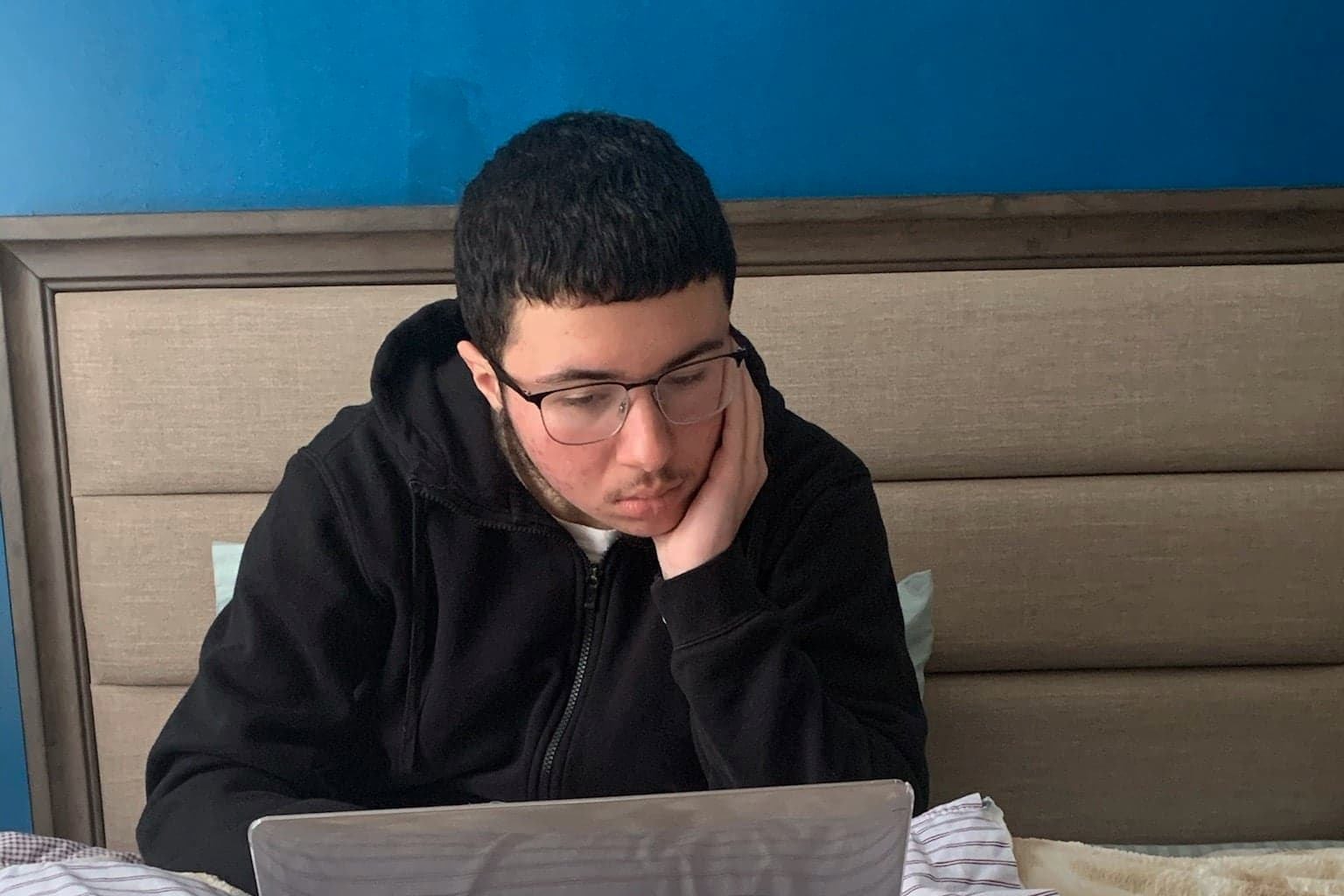

Before Science Leadership Academy was forced to close its doors last year over asbestos concerns, Ashton Krause, 17, was in the process of creating a student support group for LGBTQ students at the school just north of Center City.

Now with district students forced to learn virtually, Kraus believes a group is needed more than ever because of circumstances LGBTQ students may experience during remote learning.

“LGBTQ kids are stuck in their house and you don’t know if their parents accept them or what their situation is at home,” he said. “It puts a lot of pressure on LGBTQ kids especially if they are in an uncomfortable environment and they have to be there all day. That can be overwhelming.”

For some LGBTQ students, remote learning has removed them from physical bullying at school, but virtual classrooms don’t always provide safe, protected spaces filled with support.

“In the flurry of getting ourselves prepared for online learning some schools may have yet to develop content that translates to an online platform,” said Lauren Overton, principal at the Penn Alexander School in West Philadelphia.

“That’s definitely something we are concerned about and want to make sure that schools are building communal spaces for LGBTQ students to have safe space. Some students who identify as LGBTQ have support, and then you have many who do not.”

Some studies indicate many LGBTQ students don’t have support at school or home. A 2018 survey by the Human Rights Campaign found that only 26% of respondents said they always feel in their school classroom, with only 5% saying all of their school teachers and staff support LGBTQ people. Some 67% of survey respondents said they had heard negative comments about LGBTQ people from family members.

“Being home around this time can be a challenge emotionally to LGBTQ students if they don’t have an outlet,” Overton said.

School district’s Policy 252

In an effort to create a safe learning space for LGBTQ students, school officials, educators and activists in 2016 designed a provision for the Philadelphia School District called Policy 252. The policy aims to protect non-binary and transgender students from discrimination based on gender identity. It also establishes specific guidelines for pronoun usage and gender neutrality in the classroom.

“The district got a lot right in approving the policy,” said Amy Hillier, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, who helped draft Policy 252 for the district. “For starters, they [the district] listened to trans students and allowed trans and queer students to help craft the policy. They established a progressive trans-affirming policy at just the right time—before Trump came to office and revoked trans-affirming guidance for public schools.”

Hillier noted she would not characterize some of the current limitations of 252 as “getting it wrong” so much as not being willing or able to take the next step of consistently monitoring and enforcing implementation.

“That’s been challenging for a district struggling with basic things like funding, attendance, asbestos/lead, and now internet access for families,” she said. “Unless and until there’s a network of social workers or other staff who have support for trans (and LGBQ more generally) students as a primary job responsibility, it’s hard to imagine all students in the district will benefit from the strong policy existing on paper.”

But glitches do exist for Policy 252 in the virtual space. For one, if a student chooses to be called a name different from their biological name, oftentimes the virtual system will go by their birth records and not the student’s requested name and hurtful to the student.

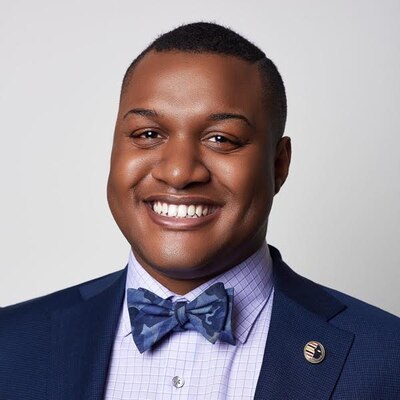

Acknowledging pronouns, addressing discrimination outside of just physical violence in Policy 252 was promising, said Ernest Owens, LGBTQ rights advocate and vice president-print for the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists.

“I don’t think enough instructors are getting proper LGBTQ sensitivity training outside of just enforcing the policy,” he said. “I would have preferred Policy 252 to mandate LGBTQ sensitivity training for staff/faculty so that they would be able to feel as if these guidelines were not just bureaucracy, but a true necessity.

“I think the first thing that needs to happen is for the district to survey LGBTQ students and families on what might be happening to them right now,” Owens added. “From there, the district should assess what needs to be adjusted/modified in the current Policy 252 guidelines to combat such discrimination in the virtual realm.”

Owens thinks politicians should amplify and support the district on these efforts without making it a politically divided issue. All students, he said, including LGBTQ youth, deserve to learn in a safe, affirming environment.

The district recently released mandatory professional development for all staff in the district to better understand Policy 252, said Rachel Holzman, deputy chief of the office of student rights and responsibilities.

“It became apparent particularly in the virtual world because we use Google Classroom that many students were feeling very unsupported by their ‘dead name’ showing up, so we changed names and gender in a way that when it flows down Google Classroom the student is reading their chosen name,” she said. “That makes the students feel supported and comfortable and this is done really between the students and me. This is a student-driven right that they have.”

A teacher who identifies as nonbinary first noticed the display name glitch on Google Classroom and brought it to the attention of school board member Mallory Fix Lopez, who championed for it to be corrected.

“I think we have the policies that support our LGBTQ students and the district is fully behind it,” Fix Lopez told Chalkbeat. “We need to figure out how all our policies are upheld and assure it’s consistent. [Superintendent William] Hite is 100% committed to this and has been a driver behind the work. He just doesn’t often get credit for it.”

Court decision a big win

A ruling by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court last week is seen as a victory for youth advocates in Philadelphia concerned about the support and safety of LGBTQ students during remote learning.

In the case, Nicole B. v. School District of Philadelphia, a fourth grader at Williams C. Bryant Elementary School in West Philadelphia, was bullied and harassed because he did not conform to male stereotypes.

When school officials failed to intervene, the classmates continued to harass the boy, and later raped him in a school restroom. The court ultimately decided in the family’s favor after years of dismissed complaints and lawsuits.

“Students who are LGBTQ or gender expansive have the same rights as other students and schools are required to intervene and correct their policies and practices that discriminate against students based on sexual orientation or gender identity,” said Kristina Moon, staff attorney at the Education Law Center, which filed an amicus brief in the case.

The successful appeal challenged the time children have to file a complaint under the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act. The normal deadline for adults is six months. Whether that six-month time period is paused for a child was an open question.

David J. Berney, the lead attorney in the case, said it addresses the statute of limitations.

“I think it implies through some of its language that students are protected from school-based bullying, based on a protected classification,” he said. “An ‘a protected classification’ is gender identity, sexual orientation.”

“In light of the decision that the supreme court issued we believe that one, students are protected if they’re being sexually harassed based on sexual orientation or gender identity; two, we believe that students now have according to the supreme court until the age of 18 and shortly thereafter to file because they would have six months after the age of 18 to file; three, for students...who are actually in a brick and mortar school right now the protections would apply as they normally would have; and finally four, for students who are doing this virtually, their classmates aren’t permitted to harass them virtually,” he said.

Berney added his fourth point is also a form of illegal harassment and can be grounds for lawsuits under the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act, because most schools recognize that cyberbullying is something that needs to be addressed and students need to be protected.

Creating safe spaces

Hurdles for LGBTQ students engaging in remote learning range from disproportionate access to internet and technology to lack of an environment that’s conducive to remote learning, said Shawnese Givens, interim executive director of The Attic Youth Center.

The Attic is the only organization in Philadelphia that exclusively serves LGBTQ youth. The pandemic has taken a toll on the center, located near 16th and Spruce in Center City. Once a hub of after-school and weekend activity, its hours have been cut to three days a week. Also, in an effort to reduce the spread of COVID-19, youth can’t currently access the physical space at the center.

“There are also other hurdles that aren’t as easily identified such as the impact of the loss of peer connection and a sense of belonging, which is particularly critical for LGBTQ young people who do not always receive acceptance at home,” Givens said.

She said it’s incredibly difficult for her staff to not be able to connect with young people in person. The opportunity to check in with a young person whose demeanor is suddenly different, or to encourage a young person to attend a particular group or meet with a case manager is not currently possible. Similarly, while virtual mediums are an excellent way to engage youth who already know about the center, they are working to find ways to engage new participants.

“It’s a difficult time for anyone who works with young people or students as we try to navigate a new landscape for our work,” Givens said. “I know that school leaders have the same concerns that we do and are attempting to find solutions to technological disparities, consistent engagement, and meeting the other complex needs of students.

“The best advice I can give to a struggling student is to know that there are adults who want to help,” she added. “Don’t give up finding the help you need. If the first person you asked wasn’t responsive or didn’t understand, keep trying. We’re here and we care.”

To help students struggling with their remote learning, workers at The Attic are providing backpacks filled with school supplies, said Hazel Edwards, coordinator of the center’s education and training department called the Bryson Institute.

At this time, the center is also offering a hot meal, food pantry items, and personal hygiene products for students.

“Our only way of engaging with young people has been virtually,” she said. “Students want to be in the building and want to be engaged and they can’t. Unfortunately those hugs or giving a young person a physical face are no more.”

Another resource for LGBTQ students is through the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, or GLSEN, said Overton, who is a founding board member for the renewed chapter in Philadelphia. The chapter hopes to grow teacher capacity and increase the number of GSAs in Philadelphia.

GSAs are groups for LGBTQ students and their allies. The acronym used to stand for the Gay Straight Alliance, but critics thought it was too exclusive, so now its called the Gender and Sexuality Alliance.

The biggest thing is to empower teachers to understand terminology and how to build an inclusive environment, Overton noted.

“Growing up I went though all of the learnings about the civil rights movement and never knew that Bayard Rustin was a gay man,” she said. “And I wonder if that would have been a positive addition to my learning so that I could have seen where other folks existed in the system who had a similar identity as me in some ways. Of course I’m a white person and Bayard is a Black man, but seeing where gay folks have been a part of movements and organizing in all things in education, it’s so important that we have opportunities to see ourselves and to see others.”

In offering advice to city students who are struggling, Krause said some good can come from online.

“You can find anybody and anything through social media,” he said. “You can FaceTime and keep up with your friends’ life and see how they are doing. That’s the only way to keep in touch with people nowadays. Especially when stuff like the pandemic happens.”

Online resources for LGBTQ students:

The Attic Youth Center

The center creates opportunities for LGBTQ youth in Philadelphia to develop into healthy, independent, civic-minded adults within a safe and supportive community. The Attic is currently offering book bags with school supplies and providing hot food and hygiene products for students.

(215) 545-4331

Want to start a GSA at your school?

Learn the steps to start a student group at your school through GLSEN.

GLSEN School Council

Provides space for LGBTQ students to be leaders.

Preferred name request

Transgender and gender nonconforming students can use their preferred name for virtual learning such as Google Classroom. Have a teacher, principal or staff member fill out this form.

Additional resources from the Education Law Center

The Rights of LGBTQ, Gender Non-Conforming and Nonbinary Students

Understanding cyberbullying