A Tennessee lawmaker has quietly postponed a bill that details a process for the state to take over school districts falling short of their academic goals.

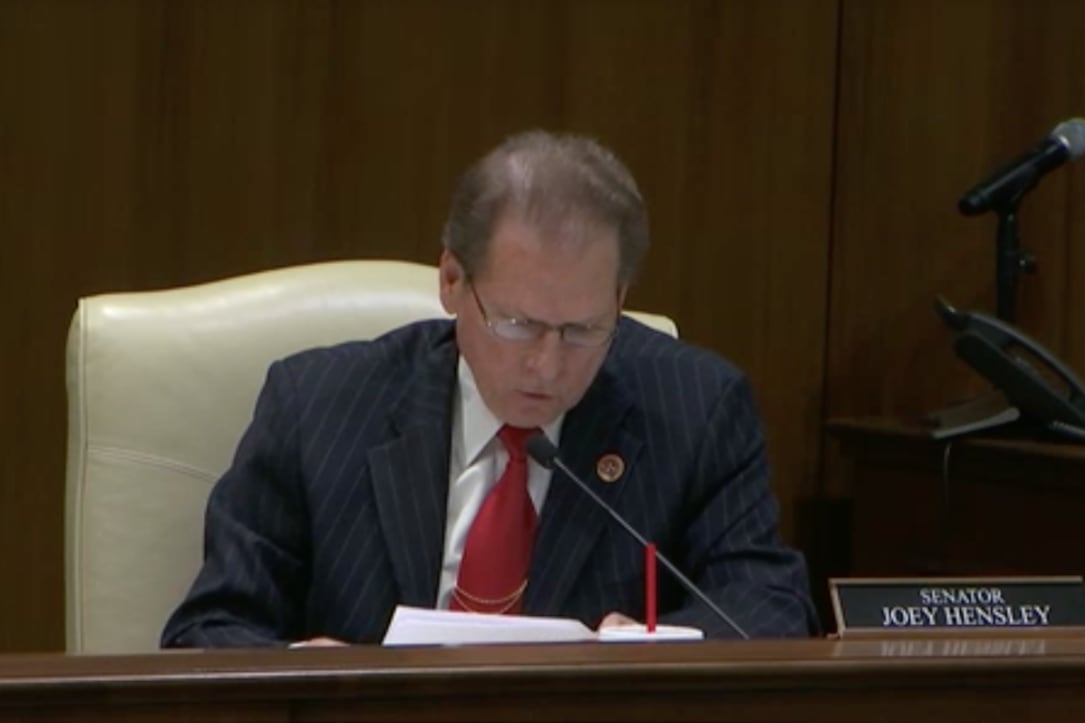

Without comment and amid a flurry of other legislation this week, Sen. Joey Hensley delayed the measure in the Senate Education Committee until next year.

Staff for Hensley referred all questions to Rep. Scott Cepicky, the bill’s House sponsor. Cepicky said Friday that he supports the delay until January of 2022, when lawmakers will kick off the second year of the two-year legislative session.

The action backs off of a proposal that has escalated tension between GOP lawmakers and school systems in Memphis and Nashville over reopening school buildings during the pandemic.

Two Nashville Democrats, Reps. Mike Stewart and Bo Mitchell, said the bill is aimed at those districts, which also are in litigation with the state over school funding and vouchers. They warned of an impending “power grab” in Tennessee’s two largest cities, where the state already has taken over low-performing schools and assigned them to charter operators that mostly have struggled to improve them.

But Cepicky, a Republican from Maury County, near Nashville, said the bill is intended to bring clarity to a state law that already gives Tennessee’s education commissioner the authority to take control of a district. That includes potentially firing a local superintendent and replacing elected school board members if the Tennessee State Board of Education approves.

“I still think it would be prudent to have a clearly defined process in place to make sure all avenues are exhausted before the state would take that ultimate action of taking over a district,” Cepicky told Chalkbeat.

For now, he said, the proposal has sparked dialogue with local school leaders.

“Since we filed this bill, we’ve been having significant movement and communication with superintendents, school board members, and Commissioner [Penny] Schwinn,” Cepicky said, declining to offer specifics. “Maybe we can continue to get that cooperation and revisit this next year.”

Both Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools and Shelby County Schools, based in Memphis, reopened their brick-and-mortar classrooms in recent months after GOP lawmakers threatened to take away state funding.

The takeover legislation, which passed last month in a House subcommittee, would authorize the commissioner to develop an improvement plan or assume “all powers of governance” for any district that is not meeting, or historically has not met, performance goals and measures set by the state board. It defines a district’s academic shortcomings as not meeting its responsibilities to one or more “priority schools” in the state’s bottom 5%, or certain schools that have significant achievement gaps among student groups.

The commissioner also could factor in district “competence” in meeting operational and fiscal responsibilities, as well as following federal and state laws, rules, regulations, policies, and guidelines.

“If you’re doing everything you possibly can and acting in the best interest of your students, this process would never apply to you,” Cepicky said. “But if you are concerned about this bill, maybe you need to take a look in the mirror to see if you’re doing everything you can for your students.”