Tennessee public schools and universities would not be allowed to require employees to take “implicit bias” training under legislation filed this week by two state lawmakers.

The legislation also would apply to employees of Tennessee’s education department and state Board of Education.

Currently, it’s up to local school districts, charter schools, and the state to set personnel policies that may or may not include implicit bias training for their employees. Such training is designed to increase self-awareness around subconscious prejudices and stereotypes that may affect how individuals see and treat people of another race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic background.

A significant amount of research in education says that such biases may contribute to racial disparities, such as differences in student achievement, learning opportunities, and school discipline between Black and white students. But it’s less clear whether training about implicit bias actually changes behaviors.

The Tennessee bill comes about two years after the state became one of the nation’s first to enact a law limiting how race and gender can be discussed in the classroom, including conversations about systemic racism. Last year, the GOP-controlled legislature passed another law that could lead to a statewide ban of certain school library books, some of which deal with matters of race and gender.

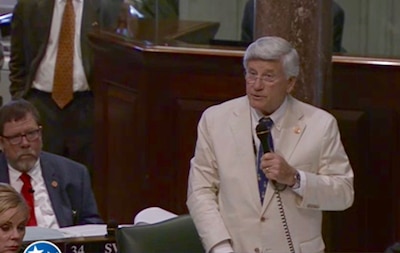

State Sen. Todd Gardenhire of Chattanooga, who is co-sponsoring the bill with fellow Republican Rep. Jason Zachary of Knoxville, said the measure is needed to protect school employees from policies that could lead to disciplinary action or firing. He cited the case of a Texas nurse who said she was fired by a hospital last year for refusing to take a mandatory course that she said was “grounded in the idea that I’m racist because I’m white.”

“It’s about having to admit to something that you’re not,” Gardenhire told Chalkbeat on Thursday.

Gardenhire, who is white, noted that his legislation would prohibit “adverse licensure and employment actions” in schools or education-related agencies if an employee refuses to participate in such training.

Senate Minority Leader Raumesh Akbari, a Memphis Democrat who is Black, called the proposal “a step in the wrong direction.”

She cast the legislation as a continuation of politically motivated national conversations that seek to pit people against each other instead of fostering policies that promote understanding, respect, and reconciliation among people of different races and backgrounds.

“That is a bill that I think is damaging to children,” Akbari said. “At the end of the day, we want to make sure that they have the safest, most equitable and fairest opportunity when they go to school.”

Implicit bias can hurt people of certain races and backgrounds in their interactions with numerous institutions — from law enforcement and criminal justice to health care and education.

In Tennessee, students of color make up about 40% of the state’s public school population, while teachers of color make up about 13% of its educators.

Mark Chin, a Vanderbilt University assistant professor who studies racial bias in education, said his research published in 2020 suggests a need to address bias in the classroom.

Using national data, he and his colleagues found larger disparities in test achievement and suspension rates between Black and white youth in counties where teachers hold stronger pro-white/anti-Black biases.

But implicit bias training is not enough to significantly change outcomes, Chin said.

“A single session where people are told of implicit biases is less impactful than sustained, embedded conversations around implicit bias,” he said.

It’s unclear whether or how many school districts or charter schools across Tennessee have policies that require employees to participate in implicit bias training.

Elizabeth Tullos, a spokeswoman for the State Board of Education, said Tennessee does not require such training within its agencies. However, staff members for the board, which sets rules and policies around education, go through the state’s required annual training on workplace discrimination, she said.

Brian Blackley, a spokesman for the state education department, said his agency doesn’t require its employees to participate in implicit bias training either and has not taken a position on the legislation.

The bill defines implicit bias training as any program that presumes an individual is “unconsciously, subconsciously, or unintentionally” predisposed to “be unfairly prejudiced in favor of or against a thing, person, or group to adjust the individual’s patterns of thinking in order to eliminate the individual’s unconscious bias or prejudice.”

You can track the legislation on the General Assembly website.

Marta Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.