Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

The Kuspuk School District owns two small planes and employs a pilot to stay connected with schools spread across 12,000 square miles along the Kuskokwim River in western Alaska.

And to keep those schools staffed, the remote school district works with its own immigration attorney.

Some 60% of Kuspuk’s certified teachers come from the Philippines. That includes all of the special education teachers and all of the teachers at five of the district’s eight currently operating schools. (A ninth school is temporarily closed.)

Most of those teachers hold J1 visas, a cultural exchange visa that allows people to work in the United States for up to five years before returning to their home countries. But a growing number in Kuspuk and in rural districts around the United States hold H1B visas, which allow for longer-term work. That matters in tight-knit rural communities, where connection is key but teacher turnover is high.

Last month, President Donald Trump issued an order to impose a $100,000 fee on new applications for H1B visas, part of a broader effort to restrict immigration and preserve opportunities for Americans. The order focuses on tech sector jobs, which account for the majority of H1B visa holders and where critics argue that foreign-born engineers and programmers have crowded out Americans.

Proponents say that companies can afford the fee if they’re bringing on truly exceptional employees who will generate more than that in profit — otherwise those jobs should go to American workers. But the fee could make it nearly impossible for rural and underserved districts like Kuspuk to hire enough teachers for hard-to-fill jobs, district leaders said.

Kuspuk Superintendent Madeline Aguillard said many of the American teachers she hires are inexperienced new graduates, and many don’t stay long. Grow-your-own programs that train people from small communities to be teachers hold promise, but they’re slow. The international teachers who work in her district’s far-flung villages aren’t a short-term stop gap, she said. They’re a critical part of the long-term workforce — and they stay for years.

“We are able to hire more experienced teachers,” she said. “I have multiple teachers with doctorates. They max out our pay scale. They are top-notch teachers that we can put in front of our kids.”

Susan Nedza, superintendent of the Hoonah district in southeast Alaska, recently hired three teachers on H1B visas to fill positions in special education and high school English and math that had sat vacant for an entire school year. A $100,000 fee would be “absolutely devastating,” she said.

“No district could afford that even for one teacher, much less multiple teachers,” Nedza said. “We would have so many students without teachers.”

Teachers on visas make up a relatively small share of the total teacher workforce and of the H1B program. Federal data analyzed by Chalkbeat indicates at least 2,000 H1B visas sponsored by school districts and charter networks were approved this year. Those teachers work for large districts like New York City, Dallas, Chicago, and Denver, and they work in one-room schoolhouses in Montana.

Many of them work in hard-to-fill positions like secondary math and science, bilingual education, and special education, but in rural districts they can be found in nearly every role, including working as principals in Kuspuk. The large majority of them come from the Philippines, where teachers are fluent in English and the educational system is similar to the United States.

While J1 teachers typically work with an agency that helps place them at no cost to the district, school districts already take on considerable administrative costs and fees — anywhere from $3,000 to $20,000 per teacher candidate, according to superintendents — to sponsor H1B visas. Some superintendents say it’s worth it to hire teachers who can work in their districts long-term. In Alaska, districts have been forced to use the H1B program after J1 agencies stopped placing teachers in school districts off the road system, where amenities, housing, and access to medical care are scarce.

The School Superintendents Association is hoping to secure an exemption from the fee for K-12 educators. The proclamation allows Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem to waive the fee for certain sectors if she finds that it is “in the national interest and does not pose a threat to the security or welfare of the United States.”

“Clearly I’m biased, but I think making sure all children have access to quality educators would be of the greatest national interest,” said Tara Thomas, senior government affairs manager for the superintendents’ group.

Whatever the dynamics are in the tech sector, they don’t apply to rural schools, said Tobin Novasio, superintendent of the Hardin school district in Montana. He’s not outsourcing American jobs or undercutting wages, he said. On the contrary, teachers on visas tend to earn more because they have more experience and education.

“The mindset is that this is a Silicon Valley thing where this is a quarter-million-a-year engineering job, and they’re bringing in an Indian engineer to do it for half the price,” Novasio said. “That’s just not the situation.”

Hardin serves about 1,800 students, most of them on the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations. Out of 150 certified teachers, 27 are on J1 visas and two are on H1B visas, with a third H1B visa pending. Fully half of Novasio’s special education teachers are visa holders.

“The value of the H1B and the reason we’ve been trying to find pathways, is that once they’re here, they can stay here and stay part of the community,” Novasio said.

Districts are working to increase the supply of American teachers, he said, but it’s a slow process.

“We’ve been very deliberate in building relationships with our local colleges,” Novasio said. “We’ve started a para pathway and have four people in that program. We’re starting an apprenticeship program. We increased our starting salary by $5,000. We’re trying everything we can.”

H1B visas allow districts more stability

The Kuspuk School District had always struggled with staffing, Aguillard said, but Alaska schools used to be able to draw teachers from the lower 48 with higher salaries, even if they didn’t stay long.

But other states have raised their pay — and milk doesn’t cost $16 a gallon in Washington State. The villages in the Kuspuk district are only accessible by plane or, in the summer, by boat. Some villages don’t have stores, and some teachers have to live in their schools because there isn’t any other housing.

“It’s difficult to get here, it’s difficult to live here, it’s difficult to function here,” Aguillard said.

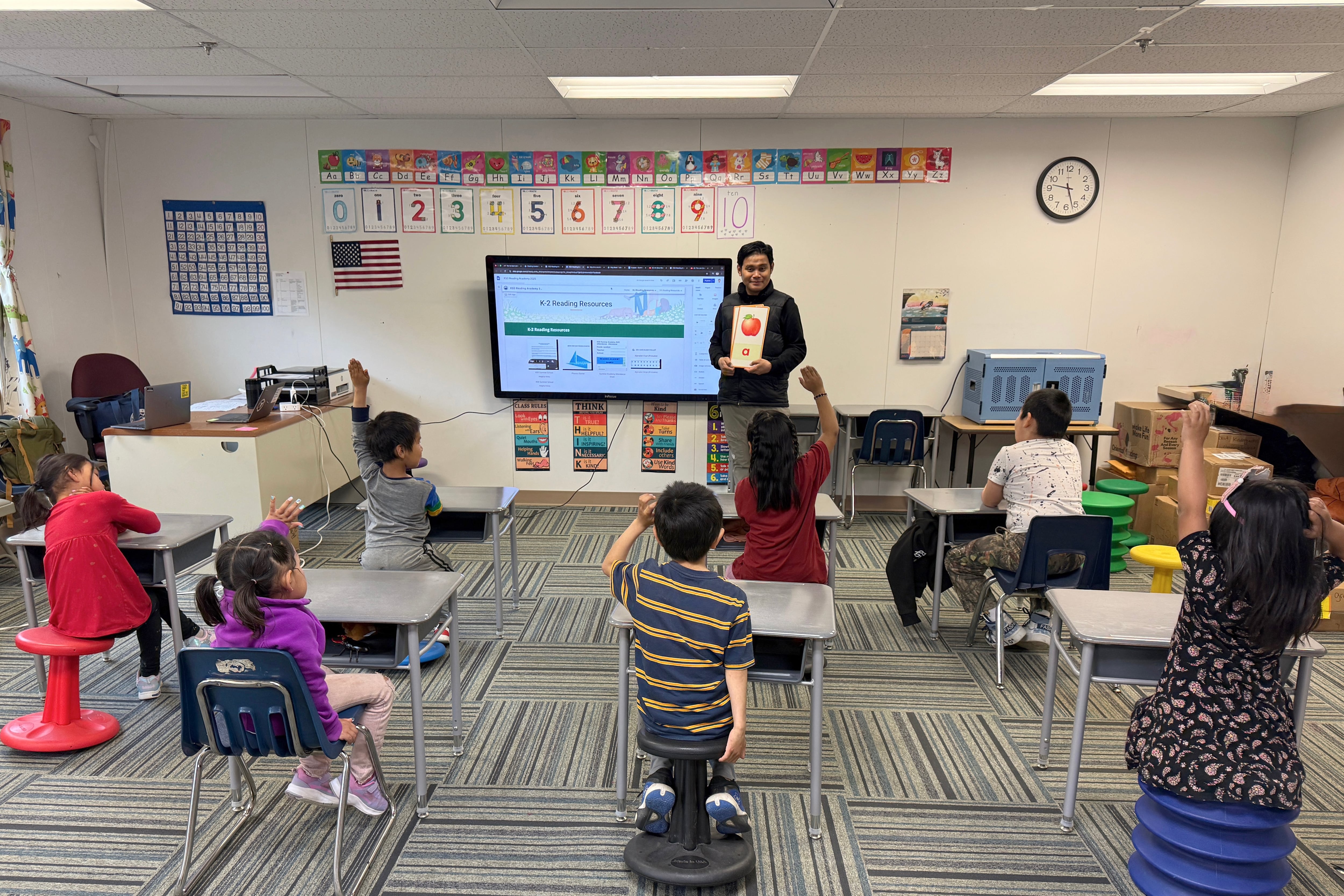

She hired her first international teacher after she had four of five special education teacher positions open and didn’t receive a single application from an American teacher. That teacher, Dale Ebcas, came from the Philippines and is still with the district six years later. He works with preschool through second grade students at Joseph and Olinga Gregory Elementary School in Kalskgag and helps with case management for high school students. With support from Aguillard and the district’s immigration attorney, he was able to convert his J1 visa to an H1B, a difficult process.

It wasn’t an easy adjustment — “I had never seen snow,” he said — but Ebcas said he was drawn to the small class sizes, low student-teacher ratios, and opportunities for professional growth, along with a competitive pay scale. He fully intended to return to the Philippines at the end of his tour, but as he approached his fifth year, the district didn’t want to lose him and he didn’t want to leave his students.

“It takes time to build relationships and trust,” Ebcas said. “It’s really important for the students here. With the community being so welcoming, I really wanted to continue and help the kids.”

Ebcas hopes the federal government considers the needs of rural and underserved schools.

“If exemptions are not given, it would really close the doors for international teachers who bring their skills and knowledge,” he said.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica atemeltzer@chalkbeat.org.