Amid the first chaotic weeks of remote learning last spring, as headlines flashed a growing unemployment rate and businesses across Chicago shut down, Rebecca Coven’s students were suddenly missing class. The reason? Work.

Like thousands of people across Chicago, the students at Sullivan High School in Rogers Park found themselves facing an economic crisis. In some cases, a family’s main breadwinner had died of the virus. In others, parents lost jobs or had their income cut. Some of Sullivan’s immigrant families weren’t eligible for government aid. In those cases, students took jobs to help make up the difference.

As school counselors and social workers were inundated with requests, Coven saw a need for immediate action. At stake was her students’ education, Coven said: “We can’t teach our students unless they have their basic needs met.”

With a handful of other educators at the school, Coven launched a Google questionnaire to ask families what they needed and a GoFundMe to solicit donations. Six months into the coronavirus crisis, Sullivan’s group has raised more than $11,000. They have given 25 families varying amounts based on need.

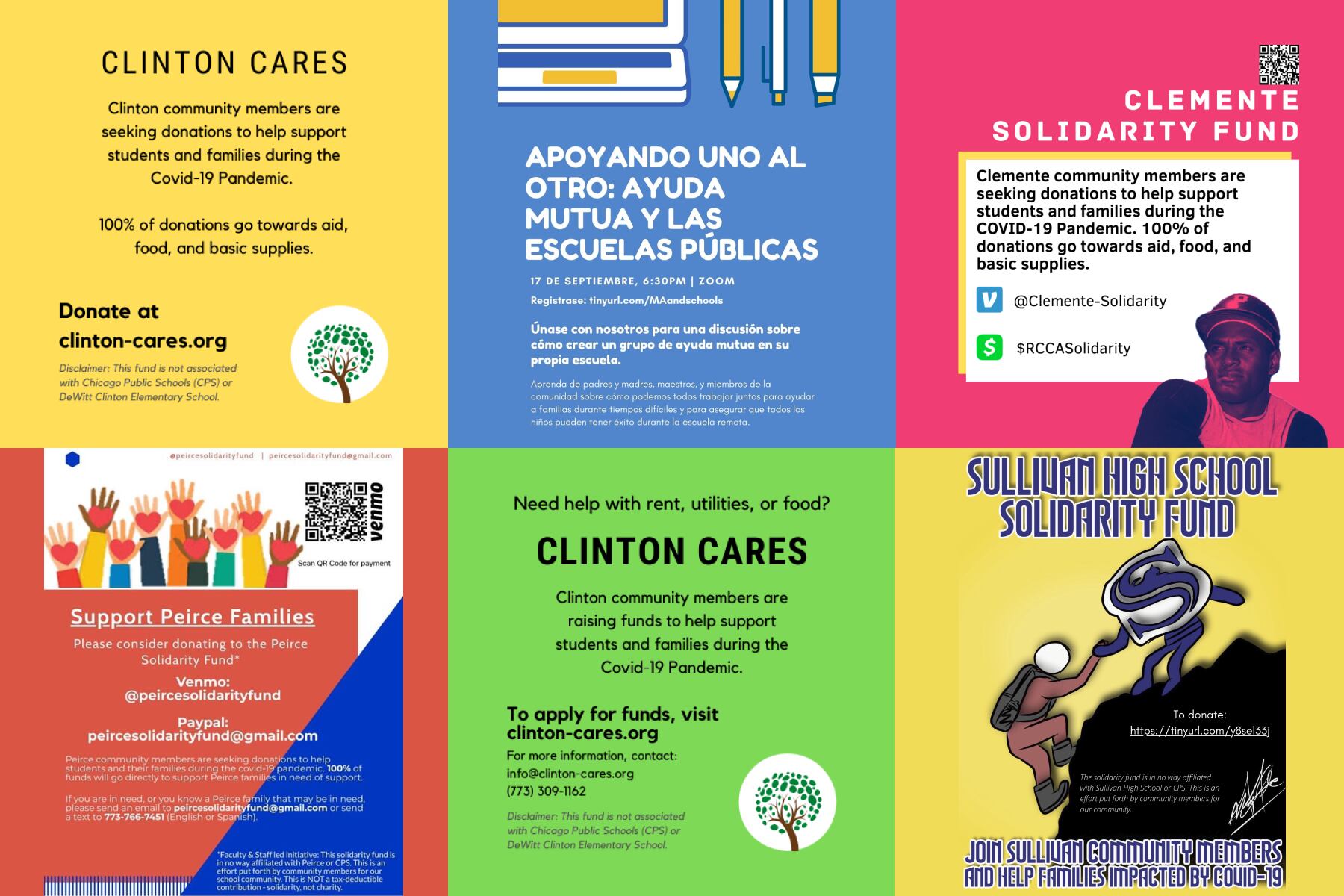

Across Chicago, teachers at other schools have done the same, with around 20 schools putting together impromptu mutual aid groups — as efforts led by ordinary people to meet social needs are called — to help families buy groceries, cover medical bills or pay rent.

Schools have long played a central role in providing social support services to families. In Chicago, where 76.4% percent of the district is low income, district officials swiftly set up food distribution efforts after school buildings closed in March. The district also runs a philanthropic nonprofit called the Children First Fund, and education nonprofits like Community in Schools expanded their work this spring from counseling to helping families meet basic needs.

The need has continued to outstrip demand. Chicago’s unemployment rate hovers at 12.6%, up significantly from 3.6% in February. The first round of eviction moratoriums and city housing grants have expired or been used up. And yet Chicago’s neighborhoods — and the students in them — continue to hurt financially.

School-based mutual aid networks may not be able to keep families afloat, but they offer a relatively quick turnaround for support, with little paperwork, and flexibility to meet needs that range from groceries to rent. Crucially, they rely on the relationships built in schools —and the organizational prowess of teachers.

Fatima Salgado, a special education teacher at Lara Academy, said she and other teachers learned a lot about families’ home situations in the first weeks of the shutdown, from assisting with remote learning to helping set up the internet. “We know what is going on behind the curtains in their home,” Salgado said.

That helped them decide how to prioritize their assistance funds - the more compounding hardships a family faced the higher priority they had to receive help.

At Roberto Clemente Community Academy in Humboldt Park, the mutual aid group runs a social media campaign every payday to encourage teachers to donate. The group also takes money through a GoFundMe and phone apps like CashApp or Venmo. Requests for financial support, made through a Google form, feed into a spreadsheet. Then a staff member checks with the student or family to figure out the urgency of the need.

Economic insecurity isn’t new for that community, says teacher Mueze Bawany, but the scope is. “I used to stock my classroom with food: bread and peanut butter and jelly, ramen noodles and stuff,” Bawany said. “After COVID the demand for support went up and we needed something more formal and we needed to expand our efforts.”

The Clemente group has raised $34,288 in about six months, the vast majority of which they distributed. Each payment and who it went to is painstakingly chronicled, and the group hopes to create a program for recurring donors.

The innovations at each school and what support they provide reflects the local communities.

Clinton Elementary in West Rogers Park has a high number of immigrant families, so their intake form is in English, Spanish, Arabic, Urdu, and Hindi (the school has also been able to accommodate the needs of many Rohingya families, despite their language having no written form). Teachers at the Jahn School of Fine Arts bought a portable washer for a family who was at risk of contracting COVID but didn’t have home laundry. At George Washington High School on the Southeast side, many members of the mutual aid group eventually became the core of teachers who organized in favor of removing school police this summer.

Using donations solicited on social media or through communities isn’t new for Chicago schools. The website DonorsChoose, a schools-specific fundraising platform, is full of teachers soliciting support to build a class library or purchase class journals.

But the mutual aid groups, operating outside of formal nonprofit status and without a specific legal standing, have had to tread carefully. Most teachers note their groups are not a formal project of their schools, even though many administrators are supportive. A workshop run by the Chicago Teachers Union’s Latinx Caucus in May offered a how-to for schools looking to start their own group.

Working with established nonprofits or other mutual aid groups has also helped the groups sustain their work.

Avondale Mutual Aid, a group of volunteers, some of whom work with schools in their day job, have run donation drives for school supplies and computers for remote learning along with food or financial support.

Kate Walsh, a volunteer with the Avondale group who works with a Chicago Public Schools art partner, is currently overseeing volunteer efforts to scrub donated computers for neighborhood families who have multiple children and not enough devices. “We wanted to make sure families in Avondale and beyond were prepared no matter what,” said Walsh. Currently, they are expecting about 40 donated computers, with 28 already in hand.

In Back of the Yards, a mostly Latino community on the Southwest side with a long history of organizing, six schools formed a new group, called Assistance for Back of the Yards Families, with the existing Brighton Park Neighborhood Council to streamline requests and fundraising efforts.

Still, the groups haven’t always been able to meet the demand. By June they had helped more than 50 families but had run out of funds; it took several weeks to clear a waiting list.

Six months into the pandemic, the economic reality in Chicago remains bleak. With the new school year starting, the mutual aid groups say they plan to continue their efforts. They say it’s essential for students to focus on their education without the looming shadow of a precarious housing situation or food insecurity.

At Clemente, they have seen donations from small businesses drop off as they themselves struggle or are shut down. But just this week, teachers and support staff involved in the mutual aid project met to create a recurring program for both donors and recipients.

Teachers say the mutual aid efforts have given them a stark knowledge of their students’ realities, but hope in the power of their communities.

“The whole thing of, it takes a village, definitely has so much truth to it,” said Salgado. “ If we don’t help, who will?”