A new study makes the bold claim that the wide-ranging education reforms embraced by Denver Public Schools were among the most effective in U.S. history at boosting student learning.

In the 11 years from the 2007-08 to 2018-19 school years, Denver students got the equivalent of 12 to 12½ years of learning compared with students in comparable Colorado school districts, researchers at the University of Colorado Denver found.

Denver’s graduation rate also increased at a higher rate than it would have if the reforms hadn’t happened, researchers found. Just 43% of Denver students graduated in four years in 2008. By 2019, 71% did. Without the reforms, the rate would have remained below 60%, the study says.

During that same 11-year time period, Denver made it easier for families to exercise school choice, creating a common application for every school in the district. The district expanded the number of independent charter schools and gave district-run schools more autonomy. And the school board closed or replaced schools with low test scores.

Since 2019, a Denver school board backed by the teachers union has questioned the reforms and rolled back some of them, including the practice of closing low-performing schools.

“The debate over Denver’s reforms, as I’ve seen in the political arena, has been extremely heated but is not often grounded in facts about the actual impact of the reforms,” said lead author Parker Baxter, the director of the university’s Center for Education Policy Analysis.

“My hope is that this study can provide a fact base.”

The study has some limitations. It looked only at district-level academic data, not student-level data, making it hard to tell which reforms worked and which didn’t. With student-level data, for example, researchers could tell whether students at a school that was closed for low test scores got higher scores at their next school.

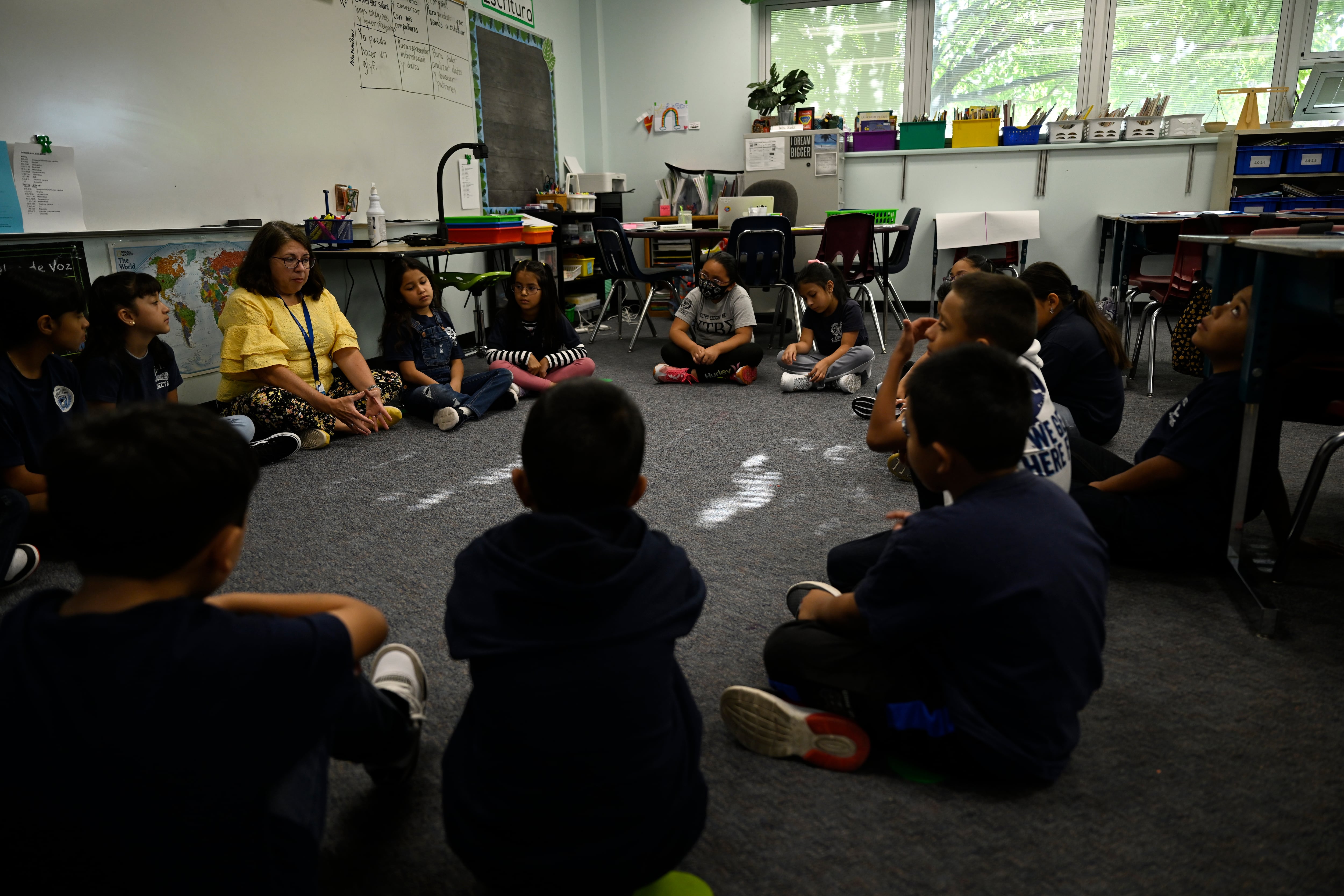

The study methodology also makes it hard to tell how different groups of students fared. Denver is a diverse district whose student body is 52% Hispanic, 14% Black, and 25% white. About 65% of students qualify for subsidized meals, an indicator of low family income.

The study shows that the academic results, based on state test scores, were positive for white students in literacy and math. They were also positive for Black students in math.

The results were positive but not statistically significant — meaning the results were more uncertain — for Black students in literacy, and for Hispanic students in literacy and math. The results were also positive but not statistically significant for students from low-income families.

White students in Denver have long scored higher on state tests than have Black and Hispanic students — so much so that Denver has the largest test score gaps by race in the entire state.

But Baxter cautioned against concluding that the reforms benefited white students the most.

“This study does not show that white students benefited more from the reforms than other students,” he said. “It shows that all students made progress.”

Doug Harris, a professor and education researcher at Tulane University who reviewed the University of Colorado study, said it shows that the results of the reforms on the average Denver Public Schools student were “quite substantial.” Before the reforms, Denver scored in the fifth percentile of Colorado districts on state literacy and math tests. By 2018-19, the district scored in the 60th percentile in literacy and the 63rd percentile in math.

But the district also experienced explosive growth, going from about 72,000 students in 2004-05 to 92,000 students in 2018-19. Increased enrollment was one of the goals of the reforms, but Harris said the addition of 20,000 students throws another variable into the mix.

Even though the researchers controlled for gentrification and found its effects were separate from the effects of the reforms, Harris said that if those 20,000 students came from wealthier families or their parents had higher levels of education, those factors could have played a part.

“The results suggest there was improvement, and I believe a solid share of that was due to the reforms,” Harris said. “How much of it is a little hard to tell.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.