Aysha Shamin has a long list of calls to make. With just a week to go before classes are set to begin in Hamtramck Public Schools, Shamin and other district parents are once again calling dozens of families to make sure they were all set for remote learning.

Speaking in Bengali, Shamin asks families if they have the technology they need to access online courses, and if they want to send their children to a physical classroom twice a week for extra help. Other parents call to ask the same questions in Arabic and Bosnian.

As many Michigan children return to online classes this fall, educators warn that online instruction — already challenging for most students — will be especially damaging for students who don’t speak English. In theory, this would be terrible news for the Hamtramck school district: 64% of the district’s students are classified as English learners, while another 14% are former English learners who have learned enough to leave the program.

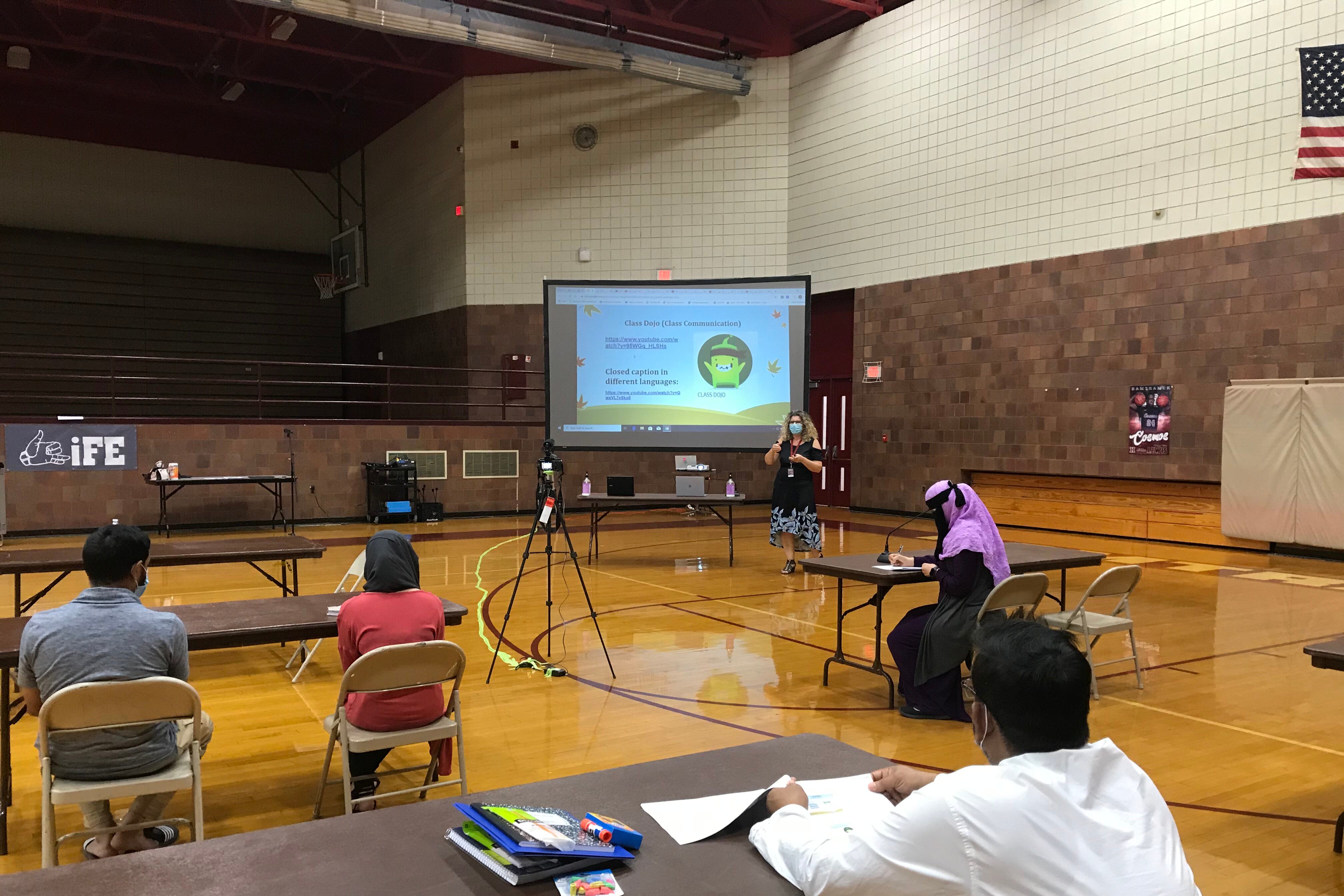

Instead, Hamtramck’s pre-pandemic support systems for immigrant families have ensured that students don’t fall through the cracks. A team of bilingual parent liaisons, hired two years ago to support newcomers from other countries, worked through the summer to ensure that families had access to food, laptops, and an internet connection. An in-person orientation held weeks before the first day of online classes helped hundreds of U.S. newcomers navigate the challenges of remote instruction.

“I don’t think we had any family” whose students didn’t attend class because of a language barrier, Shamin said. “We’re still calling. We give them our number. If they need anything, they can call us any time.”

Advocates worry that English learners will be especially hard hit by the pandemic because their families are often vulnerable in several ways. They are more likely to have low incomes, face food insecurity, and avoid seeking help due to their immigration status. They’re also less likely to have access to a computer.

“Some of them just abandoned one country because of fear, and now they’re coming into another fearful situation,” said Mirjana Maros, Hamtramck’s facilitator for English language development. “It’s a journey into the complete unknown.”

Those complex challenges make relationships between parents and schools especially important, said Suzanne Toohey, an English learner consultant for Oakland Schools in the Detroit suburbs. That’s why a number of districts in the Detroit metro area are, like Hamtramck, finding ways to prioritize in-person contacts with families who don’t speak English at home.

“Hamtramck is doing all the right things,” she said. “Typically these families are underrepresented in things like a parent engagement committee, or the parents don’t know how to access the American school system. To put a face to an email name is really important for them.”

This is certainly true in Hamtramck, where 16 different languages are spoken within the Detroit enclave’s 2.1 square miles, according to district officials. A sizable minority of families are recent immigrants, and some arrive in the district with little formal education — parents may not be literate in their native languages or know how to turn on a computer, said Amra Poskovic, the district’s school and community facilitator.

That’s why hiring parent liaisons was a top priority for Superintendent Jaleelah Ahmed when she arrived on the job two years ago. Ahmed was previously the director of English learner programs in Dearborn, a Detroit-area district that is home to the largest population of Arabic speakers in the country. She recognized that supporting students learning English would be an essential part of her new role.

The district’s six parent liaisons saw their roles expand once the coronavirus hit. In addition to helping families access schoolwork online, they helped organize an in-person orientation for newcomers to the U.S. and recruited the most vulnerable students to come to school twice a week this fall for in-person help from teachers.

With thousands of students returning to school online, experts say that providing in-person instruction for the most vulnerable students can help prevent “scary” learning losses.

In order to support those families, though, districts first have to connect with them. That’s where Hamtramck has an advantage, said Jihan Aiyash, a liaison for MiStudents Dream, an advocacy group for immigrant students, and a member of the school board in Hamtramck, in an interview this spring. Even before the pandemic, the district was already focusing on its large numbers of English learners.

“If a district didn’t have it before, they’re not suddenly going to have it now,” Aiyash said, adding, “I don’t think our students are being neglected in that way.”

For the parents leading the district’s outreach efforts, this means long days and endless phone calls. Poskovic, who leads the parent liaisons, worries that it means she won’t be at home enough this fall to help her son, an English learner in the district, with his schoolwork.

The combination of record-high unemployment, the pandemic, and the language barrier has made the communities’ needs much more severe, Shamin said. She said she frequently checks in on the family of an autistic child. The father, the sole breadwinner, is unemployed due to the pandemic. They speak only Bengali, and need help connecting not only with the school district but also with their doctors and food services.

Their plight is not unusual.

“Actually, we have too many families to tell you about,” she said