About one in 10 New York City public school students is experiencing homelessness, a rate that has remained stubbornly similar for several years.

That means roughly 111,600 children were without stable housing, according to an analysis of state data released Thursday morning. As large as that number is, advocates worry that it might be an undercount — given that remote learning has made it harder for schools to identify homeless students.

The data released Thursday shows that about 3,000 fewer children were homeless during the 2019-20 school year than the year prior, a 2% drop.

In New York City, most homeless children across district and charter schools — about 65% — were doubled up in shared housing, such as with friends or relatives, according to the Advocates for Children New York report. Another 30% lived in city shelters. The remaining 5%, comprising some 5,900 children, were identified as “unsheltered,” meaning they could be living in cars, parks, temporary trailers, or abandoned buildings.

“The vast scale of student homelessness in New York City demands urgent attention,” said Kim Sweet, executive director of Advocates for Children, the nonprofit that compiled the report and provides legal services for high-needs students. “If these children comprised their own city, it would be larger than Albany, and their numbers may skyrocket even further after the state eviction moratorium is lifted.”

New York residents have some protections against evictions until at least the end of the year, but it doesn’t apply in all cases, and tenants must prove in court that they qualify for such relief, THE CITY reported.

Advocates for Children pointed out that the number of homeless students this year may exceed what’s reported. The closure of school buildings amid the coronavirus pandemic hinders school staffers’ ability to spot changes to students’ housing situations, officials at the organization said.

That echoes national trends, with fewer students across the country being identified as homeless, according to a recent study.

The pandemic has exacerbated existing disparities between homeless students and their housed peers. Many of these students have not had reliable access to the internet or technology to participate in remote learning. Those who do may be learning in a space shared with multiple family members.

“Most of the [homeless] families we’ve been talking to have been living in one or two rooms, often with multiple kids, trying to be online at the same time,” said Susan Horwitz, an attorney with Legal Aid Society. “And you know, they don’t have noise-canceling headphones, they don’t have a room to be in alone with less distractions.”

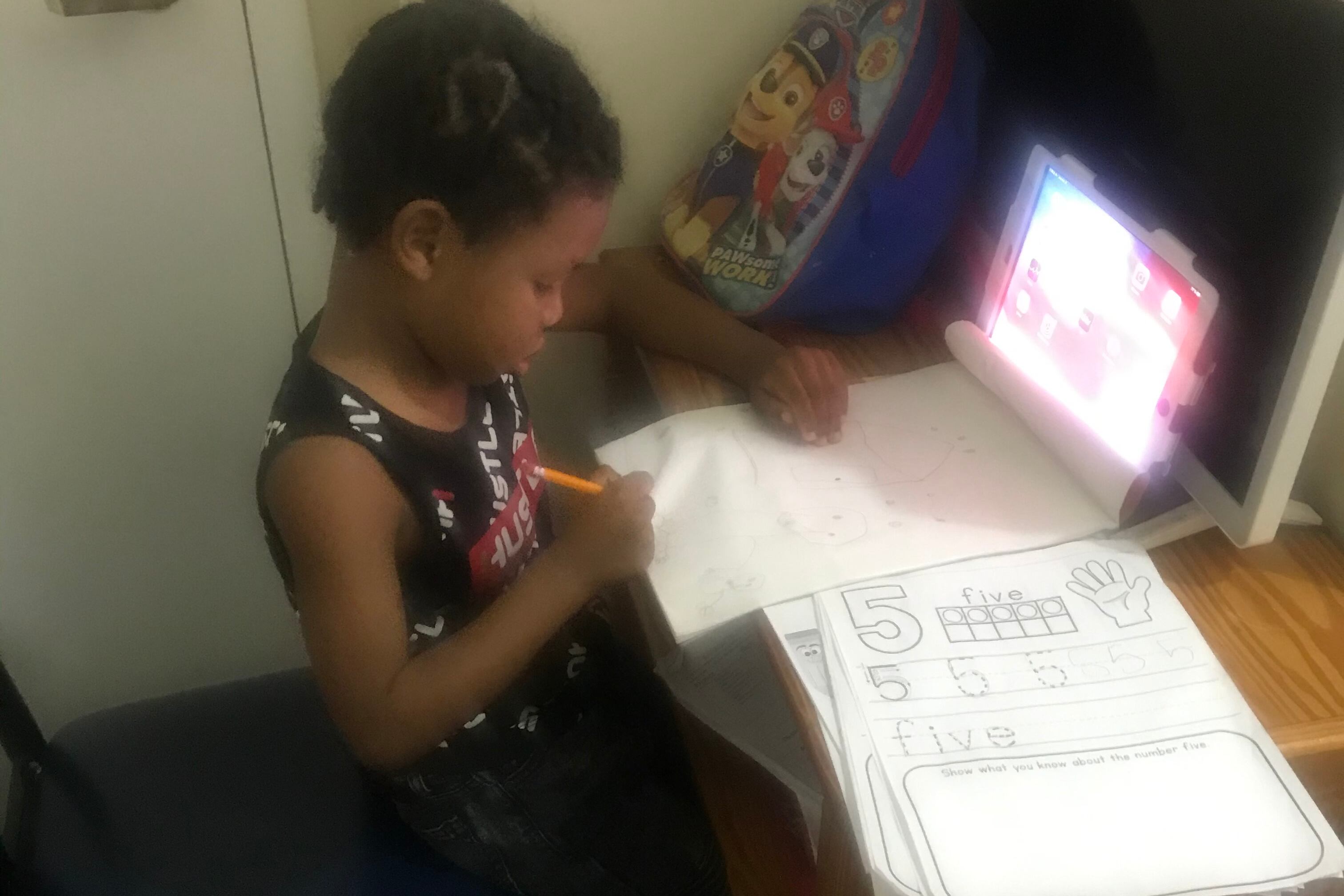

Living in a homeless shelter during the pandemic has made it difficult for Areinny Lacayo, a recent immigrant from Honduras, to secure a good education for her 5-year-old son.

There is no Wi-Fi for residents at her Bronx shelter, and the cell service that powers her son’s city-issued iPad is spotty. Often, on the two or three days a week her son is learning from home, his remote classes cut out halfway through the lesson. Sometimes Lacayo leaves the shelter to grab produce donations from local churches, but she has to pull her son away from lessons because she can’t leave him alone. She described the school and his teachers as supportive, but Lacayo — a single mother and Spanish speaker — still relies on Google Translate to translate homework for her son, who is learning English as a new language. That’s tough with unreliable internet.

Signal issues remained such a problem for Lacayo that a social worker at the shelter gave her the Wi-Fi password that staff uses. But “there are some days where the signal just fails completely,” she said. On Thursday, her son was not able to log on to remote classes at all.

“This is [my] day-to-day life, and it’s really hard right now,” Lacayo said through a translator.

Lacayo’s son is using one of the 350,000 internet-enabled iPads that the city distributed to students, prioritizing students in temporary housing, and is in the process of delivering 100,000 devices to fill remaining gaps. But Wi-Fi access remains an issue.

Such challenges means fewer homeless students “show up” for remote lessons. The virtual attendance rate for homeless students was 70% or lower at about 300 city schools during the spring. That was significantly lower than the 86% citywide average attendance rate during the same period, when attending a Zoom lesson or answering a teacher’s text message could count for being marked “present.”

After mounting pressure, the city committed to equipping all units at family shelters with Wi-Fi and also said it would quickly switch cell service providers on devices without a strong connection, according to an October announcement. But citing the difficulty in wiring up these shelters, city officials said Wi-Fi won’t become available in all of these buildings until the school year ends.

Legal Aid has since filed a lawsuit, pressing the city to complete its Wi-Fi installations at all family shelters by Jan. 4, the first day back to school after winter break.

Mayor Bill de Blasio told reporters this week that getting shelters wired “is obviously a bigger job and one we’re committed to, but that is something that we need to be realistic about the timeline and I’ll leave it there, given that it’s a litigation matter.”

Advocates remain concerned about students in temporary housing falling even further behind academically. In the 2018-2019 school year, 29% of city students experiencing homelessness passed state reading state tests, and 27% passed the math exam — nearly 20 percentage points lower than their peers who live in stable housing. Homeless students were also more likely to miss school and be suspended, a previous Independent Budget Office analysis found.

The de Blasio administration has dedicated some additional resources for homeless students, including a $12 million investment for boosting school-based supports for these children. It has also hired 100 “Bridging The Gap” social workers to serve schools with high numbers of students in temporary housing. Following a hiring freeze and budget cuts at the department of education, at least 20 positions dedicated to supporting students in temporary housing are unfilled, according to Advocates For Children.

Advocates for Children is asking the city to ensure every homeless student has proper technology, to reach out more often to students who haven’t been regularly participating in remote learning, and to offer in-person instruction to families of homeless students who want it.

This school year, the city’s child care centers — known as Learning Bridges — are prioritizing seats for homeless students, in addition to the children of some essential workers. The education department did not immediately say how many homeless children are enrolled in Learning Bridges.

Following recent citywide building closures, schools will reopen next week for 3K, pre-K, K-5 and students with the most significant disabilities. As schools figure out whether they can offer more in-person learning days, the education department is asking principals to first prioritize seats for students with disabilities, then move on to other high-needs groups of students, including homeless children and students learning English as a new language.

However, the city has not yet outlined a plan to bring back middle and high schoolers, meaning all homeless students in those grades will be learning remotely until at least the start of 2021.

“We are committed to providing our students experiencing homelessness with a high-quality education that delivers critical supports and resources to meet their needs every step of the way,” Sarah Casasnovas, a spokesperson for the education department, wrote in a statement. “These students remain top of mind during this crisis, and we continue to work closely with advocates like [Advocates for Children] and partner agencies to provide caring, supportive environments whether in-person or remote.”