New York City teachers and principals have about 10 extra days to get ready for a school year unlike any other, after the mayor and union leaders agreed to hold off on opening buildings for in-person instruction.

The delay was hard-fought, coming after hundreds of principals had written open letters demanding more time, and with just hours to spare before teachers were scheduled to vote on whether or not to authorize a strike.

Along with the announcement came a flood of emotions from teachers and principals who have been wrangling with the logistics of teaching in-person and remotely, and parents worried about the educational toll the pandemic has taken on their children.

Educators have won themselves an 11-day reprieve, but it is short compared with the list of tasks that remain undone. In those few extra days, it may be hard to convince a Bronx community hit hard by COVID-19 that classrooms are safe. One Washington Heights school still needs to hash out all of its teachers schedules. And in Lower Manhattan, a principal must train his staff to follow new safety protocols.

Meanwhile, parents who rely on school buses, many of whom have children with special needs, will be anxiously watching whether the extra days are enough for the city to figure out how to run a fleet the size of a municipality unto itself.

The scramble to reopen buildings in the country’s largest school system isn’t about to slow down. On the heels of the announcement, educators and families shared their reactions to the delay.

‘We are not elated’

In the Bronx district where Valerie Green Thomas is a middle school teacher, the number of people testing positive for the coronavirus is 35% higher than the city average. She was skeptical that more time to plan for reopening would make her feel any safer about returning to school.

“We are not elated,” she said. “It’s 10 more days to be stressed.”

Green Thomas, who works with students who have disabilities and those who have fallen behind in English, said it was hard to shake the fear “deep down inside me” of the past spring. Before the city shuttered school buildings in mid-March, campuses remained open even as teachers sounded the alarm over mounting cases. And even after schools shut down, educators reported for training to their buildings, without any word from the health department about whether they could have been exposed to colleagues or students who tested positive.

Scarred by the experience, and watching the city barrel ahead with plans to reopen despite a litany of questions about safety concerns, Green Thomas and many of her colleagues applied for, and were granted, permission to work from home because of underlying health conditions. She estimated that half of her colleagues would be staying home — many of them veteran teachers whom she described as “great” and “effective.”

“We had to decide: Are we martyrs or are we heroes? We chose heroes, and applied for accommodations,” she said.

But that has left her school with a staffing crunch that she’s not sure will be filled even with more time to try to recruit educators into classrooms.

“I think we all should do remote teaching until we come up with some concrete plans to ensure our kids will do well and our teachers are safe,” Green Thomas said. If people don’t feel protected, she added, “then teaching is going to be naught. Learning is going to be nothing.”

‘I want to meet them in person’

P.S. 8 teacher Eleni Filippatos was in a reopening planning meeting with her Upper Manhattan school administrators when she received a text message about the delay. Together, they watched the livestreamed press conference in shock as Mayor Bill de Blasio and Chancellor Richard Carranza, flanked by union leaders, announced the news. Just the day before, her district’s union representative told teachers that a strike was necessary because reopening schools was a “life or death” decision, due to the health risks of contracting the coronavirus.

But shock was met by relief for Filippattos, who said she did not want to go on strike because she felt the city’s reopening plans for reduced class sizes and mandatory masks were “over-the-top safe,” and she is desperate to help her students — English learners — in person after seeing several children struggle with remote learning in the spring. Some found it hard to focus from home, while others were caring for younger relatives while juggling school.

Filippattos, who is on her school’s reopening committee, also believes the delay will give teachers ample time to prepare for the new year. Her own school is still figuring out teachers’ schedules.

What didn’t make sense about Tuesday’s deal, she said, was the remote orientation period for students between Sept. 16-18.

“One of the main reasons I want to be back is meeting new kids for the first time,” Filippatos said, who was speaking from her Washington Heights classroom, which, beforeTuesday, she hadn’t entered since March. “I want to meet them in person. Now it’s like we’re gonna meet them for the first time online, so I feel like that’s a little counterintuitive to me personally in terms of building relationships.”

‘More time is just incredible’

New Design High School Principal Scott Conti was relieved to hear that his school will have more than a week, instead of just two days, to coordinate with his staff. That will give the Manhattan principal time to figure out a dizzying array of logistics, including how many students can go to the bathroom at once, how in-classroom lunch periods will work, and how to reconfigure classrooms to comply with social distancing rules — all the while making sure his staff of roughly 50 is familiar with all of the new regulations.

“I don’t know how many schools would have been ready to go [next] Thursday,” he said, referring to the originally scheduled start of in-person classes. “More time is just incredible.”

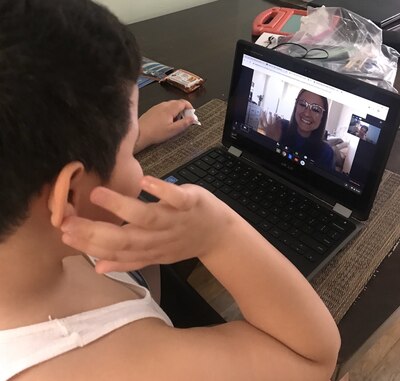

He’s also hoping to use the extra time to allow his staff to share tips and tricks for making virtual instruction work; the school is planning to conduct all teaching digitally — with teachers and students learning on laptops, even when students arrive for in-person classes so the school can quickly pivot to fully remote learning if there is a spike in coronavirus cases.

But Conti, who tested positive for coronavirus antibodies after getting sick back in March, said he is still wary of a spike in infections even after the city agreed to random monthly testing for every school. The city’s testing plan encourages, but does not require, students and staff to get tested before they arrive in person.

“Staff and students are going to come into the building with it on day one,” he said. “We’re still not safe.”

‘I’m literally running on an empty tank’

Paola Jordan, a Manhattan mom of 12-year-old twins who both have special needs, said the delay makes sense to her but she feels “mentally exhausted” by the constant updates and lack of clarity on crucial elements of her children’s education.

“Why did they take so much time to make this decision?” she asked. “I’m literally running on an empty tank right now.”

Jordan is planning to send her children to school in person as part of the city’s hybrid model, though she still has many unanswered questions. Her son is supposed to be enrolled in a class that includes a mix of students with disabilities and general education students taught simultaneously by two teachers. Even though 100,000 students with disabilities attend “integrated co-teaching” classes, city officials have not explained in detail how they will work amid a massive staffing crunch — and Jordan said she was told only one teacher would likely be available at a time.

It’s also up in the air how her children, who depend on yellow bus service, will actually get to school. The city has not formally signed any contracts with bus companies; they were canceled to save money after school buildings shut down.

“That makes me uneasy because more and more people are using the subway,” Jordan said, noting she worries about the virus spreading on crowded trains. Students with disabilities, she said, are “still up in the air when it comes to transportation.”