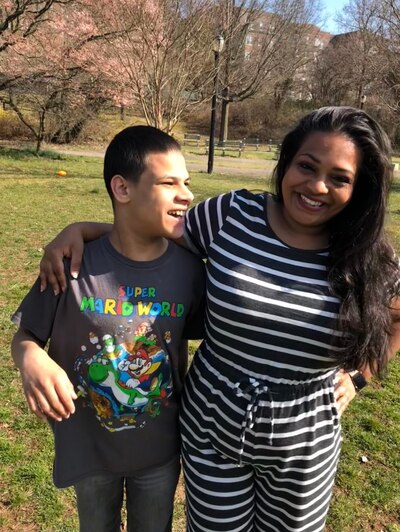

When Erika Newsome enrolled her second grader in the city’s free child care program this year, it took weeks of meetings to get the nonprofit organization running the site to support his behavioral disability.

Early on, they tried to turn her away. “I was met at the door with, ‘He’s not going to be able to come back,’” said Newsome, who lives in the Bronx.

Newsome’s experience is hardly unique: The city’s free child care program, serving children on their remote days this year, discouraged some students with disabilities from attending even as officials promised they would be prioritized. Now, as New York City officials are leaning on the same network of nonprofits to help run its expanded summer school program, some families and advocates are already seeing red flags.

“We have already heard from families who were told by their schools or [community organizations] that there would not be special education supports available this summer,” said Randi Levine, a special education policy expert at Advocates for Children, adding that community organizations have sometimes struggled to accommodate students with disabilities during previous summer or after-school programs. “What the law requires is for all students to have the accommodations they need.”

The city has touted that this year’s summer school will go beyond traditional academic enrichment and will include expanded social-emotional support and camp-oriented programs such as field trips and outdoor activities. To pull that off, the city is deploying education department staff to run the academic portion and community-based nonprofits to staff the extracurricular elements. For the first time, all families are invited to participate — not just children who are behind. City officials estimate as many as 190,000 students could enroll.

Education department officials said that students with disabilities will receive the services they need. Special education teachers and paraprofessionals will be available, and may offer individual help to students with autism, behavioral issues, or more acute medical needs. Schools should review students’ existing special education learning plans to help determine what support they need to participate in the summer program, a spokesperson said, noting that students may not receive the exact same services during the academic and camp-oriented parts of the day.

“We’ll work with families and sites to provide additional supports and appropriate services based on each student’s needs,” wrote Sarah Casasnovas, an education department spokesperson. The department is planning to host a virtual information session focused on students with disabilities on May 20, she said.

But even as sign-ups for the summer program have been open since April 26, key details remain murky. Parents were unsure how schools would determine what services they are entitled to and what role families would play in those decisions; city officials have only said that parents should reach out to their schools if they have questions. Also unclear: whether students will receive bus transportation to and from the program. (Department officials said they will make those decisions based on need and availability.)

Meanwhile, community organizations are in the dark about what training they may receive and how paraprofessionals and other specialized staff will be allocated, making it difficult for them to offer clear answers to families and potentially discouraging them from participating.

If parents get in touch about what special education staff will be provided, “We basically have to say that we don’t know yet,” said Vito Interrante, who will help oversee several summer school sites through the nonprofit Children’s Aid. “What [city officials] said was there will be paraprofessionals available for kids who need them, but there aren’t really any details about how we will get them.”

Interrante added that there could be broader constraints on staffing and wondered how many educators will sign up to work this summer after a grueling year of teaching during the pandemic.

“It’s a very enthusiastic approach to summer, but I also wonder how many teachers are going to sign up for this kind of initiative, and especially special needs staff,” he said.

Given the city’s message that all students will be invited to attend its expanded summer program, some parents said they were surprised to learn that their children won’t be eligible.

Staten Island mom Renee Marhong was initially excited to learn about the summer program. Her 15-year-old son, who has cerebral palsy as well as a cognitive delay, often can’t participate in the same camps and activities as his two siblings.

“I wanted my oldest son to have that kind of camp style [program],” she said.

But high school students who attend District 75 programs, designed for children with disabilities who require more intensive support, aren’t eligible for parts of the day supervised by community organizations, education department officials said.

Marhong’s son will still attend a summer academic program operated by his school, as mandated by his special education plan, though he will not be allowed to attend the camp-oriented option operated by community organizations after the traditional school day ends.

“It feels like a constant struggle to get seen, to get heard, to get services, to get bussing,” Marhong said. “It’s unfair — I have to figure out some type of other programming for him.”

Meanwhile, some parents and advocates remain concerned that even students with disabilities who are eligible for the expanded program will face roadblocks. That’s because the expanded summer school program is being partly operated by the same community organizations that ran the city’s child care program for remote learning days, known as Learning Bridges, which struggled to serve many students with disabilities.

After fielding complaints from parents who were turned away from Learning Bridges, the state attorney general launched an investigation that resulted in an agreement to make it clearer to parents of students with disabilities that they were welcome to attend the program. The attorney general’s office did not respond to a question about whether they are monitoring the city’s inclusion of students with disabilities this summer.

But advocates, including Levine, point out that the summer program runs less than two months, which means that if it’s not set up from the beginning, many students with disabilities may not be able to participate at all.

“As we saw with the Learning Bridges program, it’s not enough to say supports and accommodations will be available,” she said. “The summer program is short so it’s essential that all students with disabilities have the accommodations and support they need on day one.”

Correction: High school students in District 75 are not eligible for the city’s expanded summer school program that is operated by community organizations. A previous version of this story incorrectly said that they were.