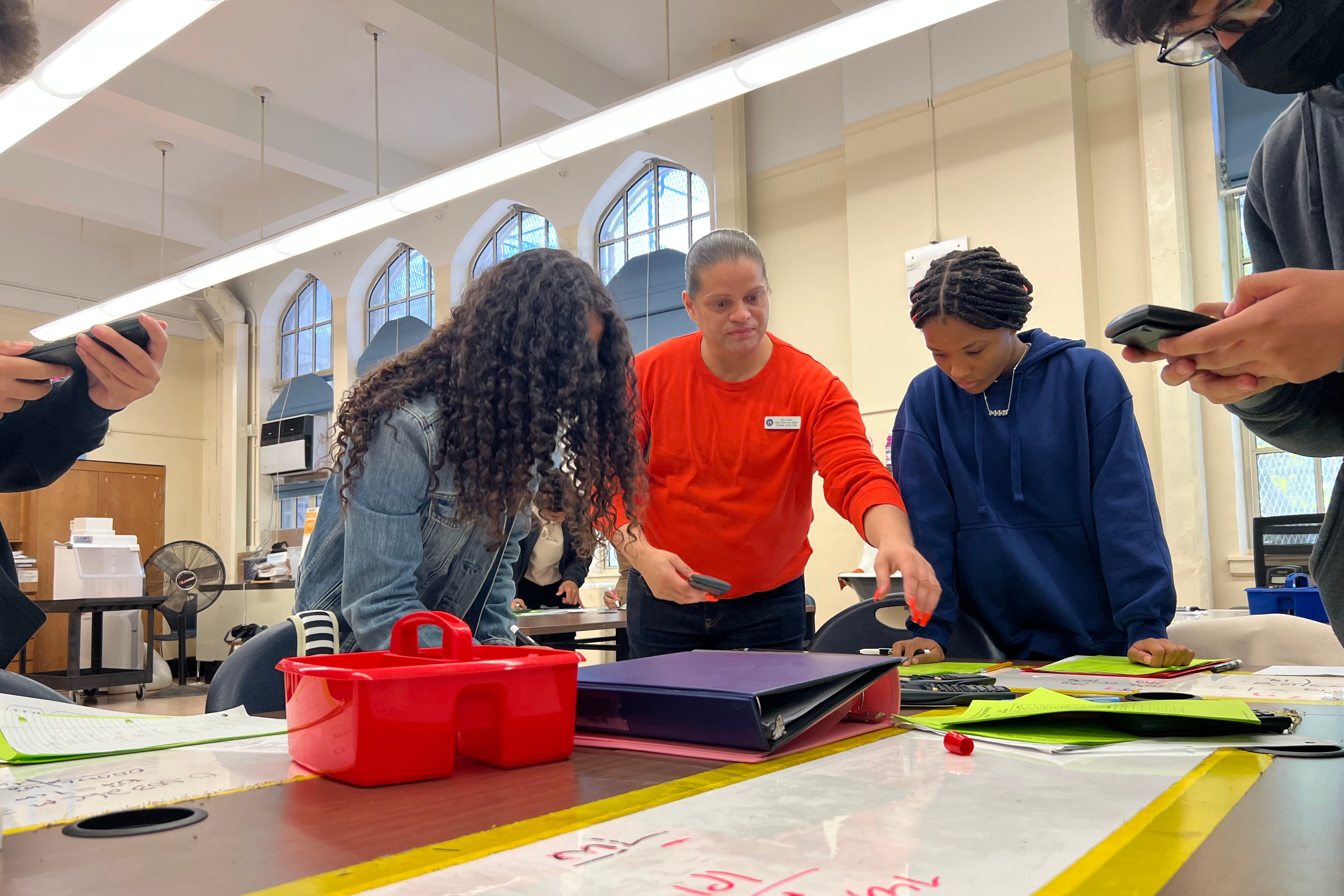

On a recent Friday morning, a group of freshman students flagged down their chemistry teacher, Billy Green. Students were in pods, tasked with completing math equations related to physical chemistry and then presenting them to Green for points.

After several failed attempts, the group of students at Harlem’s A. Philip Randolph Campus High School finally felt ready and threw up their hands.

But when Green walked over, the students hadn’t decided who would present, and then they began doubting their conclusions.

“So, I’m gonna stop you — why do you think? Y’all not ready to present,” Green said. “Even if it’s wrong, you gotta be confident in your work. I’m moving away because guess what, I have 30 other students, so y’all lost your turn, so now y’all better get it right.”

Green gave them a clue about how to fix what turned out to be incorrect work. “Are you serious right now?” one irritated student said as Green walked away.

Training students to work together, especially under pressure, is at the core of how Green, recently named New York State’s Teacher of the Year, teaches. He reminded his class that “science is about collaboration, discussion, discovery” — and revealed that it was a practice activity that wouldn’t be graded that day.

Green’s pathway to teaching was rocky, a point that was highlighted when he was recently honored for the state award. He grew up living in poverty and navigating homelessness, often squatting in abandoned buildings, while his mother battled a drug addiction. Still, he fell in love with school and education at an early age, and with the nudging of his mother and help from a trusted high school teacher, Green enrolled in college.

A few years into his first teaching job at High School For Environmental Studies in Manhattan, Green, who was untenured at the time, said he was fired for showing up late on multiple occasions. (Nathaniel Styer, a spokesperson for the education department, confirmed that Green was “discontinued” as a teacher in 2007 and began teaching full time again in 2009, but said he couldn’t provide further details about what happened.)

Green said he made those mistakes because he was not raised to know that time management was important — one of several skills he hopes to pass on to his students, hence the time restrictions on the group activity on Friday.

He’s taught at six schools over his 20-year career, including a program on Rikers Island. Asked why he’s moved around so much, he said that he intentionally leaves after a few years because he feels that other schools that predominantly serve many low-income students could benefit from his teaching methods.

Multiple former students shared glowing reviews of Green, saying that he inspired them to come out of their shell. But Green acknowledges that his teaching style and his focus on culturally responsive education are not universally loved, pointing to a recent New York Post article critical of his approach. While his former and current principal both agreed to nominate him for Teacher of the Year, he also noted that, just like any job, he didn’t always see eye-to-eye with former bosses. That earned him the nickname, “Rebel With A Cause.”

Green wants his mostly Black and Latino students to feel connected to science, a field that is still dominated by white workers. That means finding links between what he’s teaching and their backgrounds, such as introducing them to prominent scientists who look like them, or batting down stereotypes.

“What stops Black and brown people from studying mathematics,” he told the class, “is that somebody told you that you can’t make a mistake.”

Chalkbeat sat down for a brief interview with Green. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You have been talking about this collaborative model. What informed that? Is this how you’ve always taught, or is this an evolution of your teaching methods?

So I went to one of the most difficult schools in the country, Williams College … And you set the bar so high, that even the smartest that think they’re the smartest and the weakest that think they’re the weakest have no choice but to work together.

So one of the greatest models I learned from Williams College was that in order to succeed in corporate, in order to succeed in the world, you needed to know how to collaborate with different people and different places, things, communities. Part of that was always: Set the bar high, don’t stress too much about intelligence or smartness, and more so, who’s collaborating with who and who’s building each other up?

How do you sort of take how you grew up and bring that into the classroom? One of your former students mentioned that he knew where you came from, he knows your back story, and so do you talk about that in the classroom? And how do you let that inform your teaching?

I can’t wake up and take off my identities, right? So I was always taught by my mother [to] never to hide who I am, right? Always present my authentic self. So I’m Puerto Rican, like I said, Black, Italian, gay, [Williams]-educated … I learned a lot on how to survive in these environments. So, what I teach my kids is that survival, right?

And there are many moments in my subject, right, that I’m able to tell them a story, or things that I have been through because my subject, chemistry, relates to the world. I do a project called Chemistry in the City that a lot of the kids love, because every unit, they have to go out into their communities or their cultures, and bring something back that’s related to the content of chemistry, I then become a learner. Right? It’s the reason why I teach the way I teach it, because my teachers affirmed me and I know what that affirmation is like when you are a marginalized person or a marginalized identity. So, I want all students to feel that in these spaces.

At the end of class, you were talking about why Regents exams aren’t everything and then you specifically called out Black and brown people. (He said, “What stops Black and brown people from studying mathematics is that somebody told you that you can’t make a mistake.”) Can you tell me more about that?

There is a stereotype that Black and brown people hate math. They’ll tell you, “Oh, I don’t like it.” Right? They have phobias of this. There are many stereotypes that Asians perform better, or whites perform better.

I build their self esteem back up. I get them to work together to let them know that it’s okay, there’s a big misunderstanding between Black and brown people just saying, ‘We’re crabs in a barrel.’ I know this. I live in Black and brown communities. So it is my job to let them know you are not crabs in a barrel, we will uplift each other. Don’t claw each other down.

What do you feel like are the challenges of this school year?

So, the challenge that I think that the students are facing — and is the only challenge I’ve always faced in these types of schools — is the lack of knowledge of what is next. So the goal of my teaching is to teach them what they can’t get in the books, right? And that is connecting their science to their community, connecting their science to their cultures, connecting science to a career, connecting science to literacy, right, I want them to do those things. And the challenge becomes, when not everybody’s on the same page, right? Educationally, you push for certain things, and then curriculums detour you the other way.

They’ll say, ‘No, we’re not doing this,’ or, like, ‘Don’t do too much,’ like what they’re saying in the [recent New York Post] article right there. Some people just don’t get that you have to incorporate student voice, student cultures, students’ living into curriculum. They should not come in here and be robots and controlled, overpoliced. You know, that’s not what education is about. So the big thing for me, like I said, is just creating spaces that emancipate, liberate, and educate.

What comes next for you?

That’s the saddest part of this award. That everyone asks me, ‘So now you’re going to be the superintendent, the chancellor? When are you going to leave the classroom?’ Are you kidding me? My love, my passion is in the classroom. My power with these youth is in this classroom. I am going to do this for the next 80 years. I hope to live to 120 so they can see what a 120-year-old teacher can come into the building and do.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.