Parents of more than 42,000 children across Tennessee will lose access to free child care in January as federal coronavirus relief money runs out.

The Tennessee Department of Human Services child care assistance program for workers deemed “essential” during the pandemic expires Dec. 31 and the state does not have plans to renew it.

Essential workers covered under the program included people at restaurants, airports, schools, shipping and distribution centers, grocery stores, police departments, and more. The state pays the child care facility the full cost of student supervision if the parent qualifies.

These workers are often people who have lower incomes, jobs with less flexible hours, and less money to pay for alternatives when classrooms are closed. Most students in Memphis live in poverty, while about a third of students across the state live in poverty.

A department spokesman said the state has “exhausted all of its funding” after spending about $110 million on the program as of Nov. 30. Federal lawmakers are debating how to extend similar assistance programs nationwide. Tennessee started its program in April and renewed it in August. (Scroll down to see how many children the program served in your county.)

The looming expiration has left child care providers scrambling for ways to make up the funding for virtual learning centers where students can go during online learning. But they hope to keep operations going into 2021.

Shelby County Schools, the largest district in Tennessee, has kept classrooms closed to students all school year and recently delayed a return until early February — leaving a month long gap of child care for working parents.

Brian McLaughlin, the chief operating officer for the YMCA of Memphis & the Mid-South, said he has been in multiple meetings with the state this week in hopes of tapping into Tennessee’s unused dollars from the federal program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF. The state has come under scrutiny for stockpiling $741 million rather than spending it to help lift families out of poverty.

“We’re really concerned for our families and the community because these children in our care, a significant percentage of them are from households with lower incomes,” McLaughlin said. “They don’t have flexible jobs. They had no other option.”

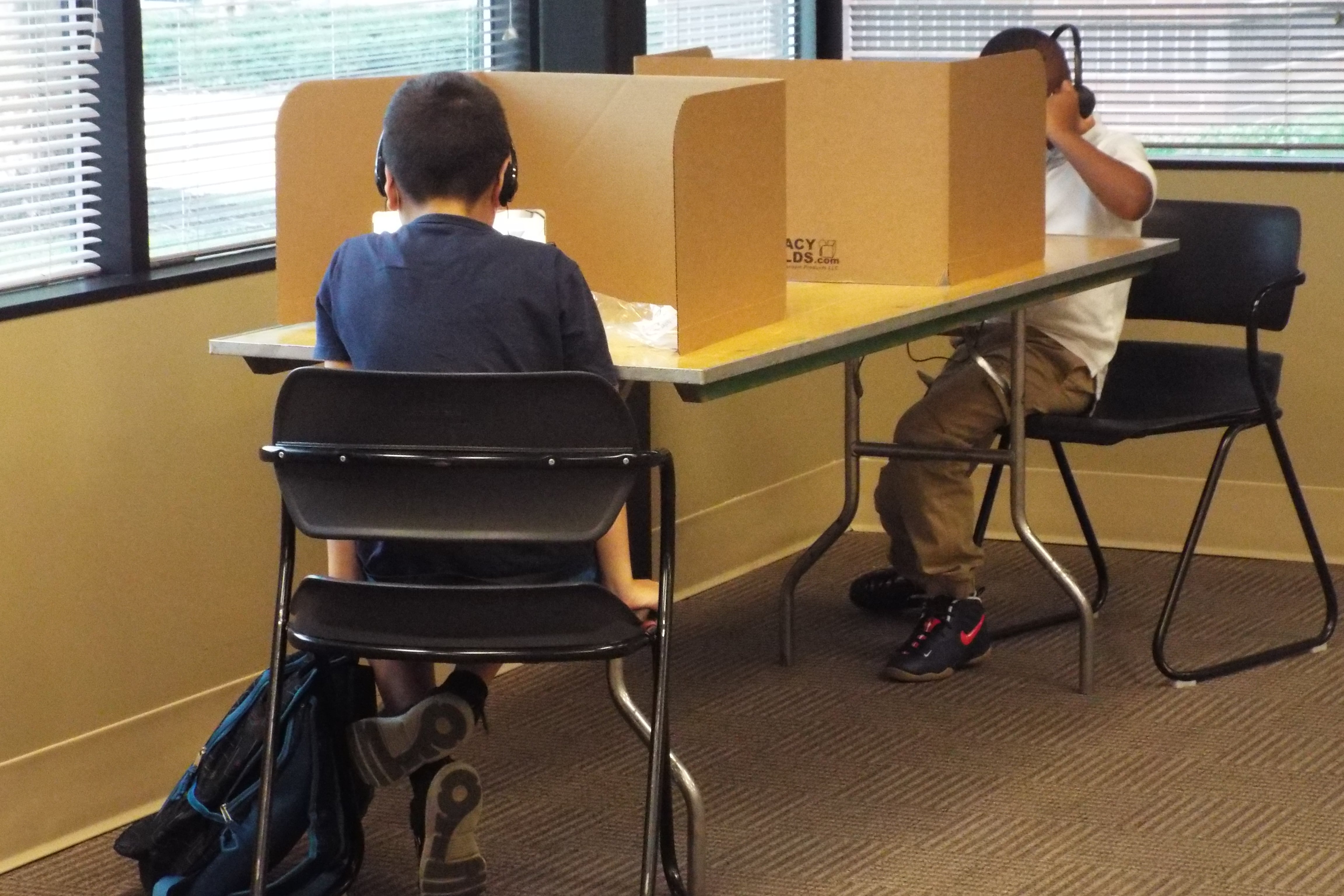

The YMCA is serving about 6,000 students at more than 50 virtual learning centers across the city. To meet the demand, McLaughlin said the organization has hired about 500 people to keep student groups small and provide the support they need during virtual learning.

He estimated it would cost $2 million to keep the virtual learning centers running during the month before Memphis classrooms are scheduled to reopen.

But some families want to continue at virtual learning centers, even if classrooms are an option. Keith Blanchard, CEO of Boys & Girls Clubs of Memphis, said staff surveyed parents of the 200 students at their five virtual learning centers. Most said they felt safer at the virtual learning centers because it’s what they’ve known.

Because his organization was “heavily reliant” on the coronavirus relief money, Blanchard said it may dip into reserves and launch a fundraising campaign to keep the centers going.

“I will raise the money somewhere,” he said. “We have committed to continuing for as long as we can.”