After months of tense community debate, the Memphis school board voted to keep sheriff’s deputies in schools and renewed its agreement with the Shelby County Sheriff’s Office.

The board unanimously passed the memorandum of understanding with the Sheriff’s Office at a Tuesday evening meeting, but not before adding an amendment to address community concerns and national conversations about negative interactions between students and campus police.

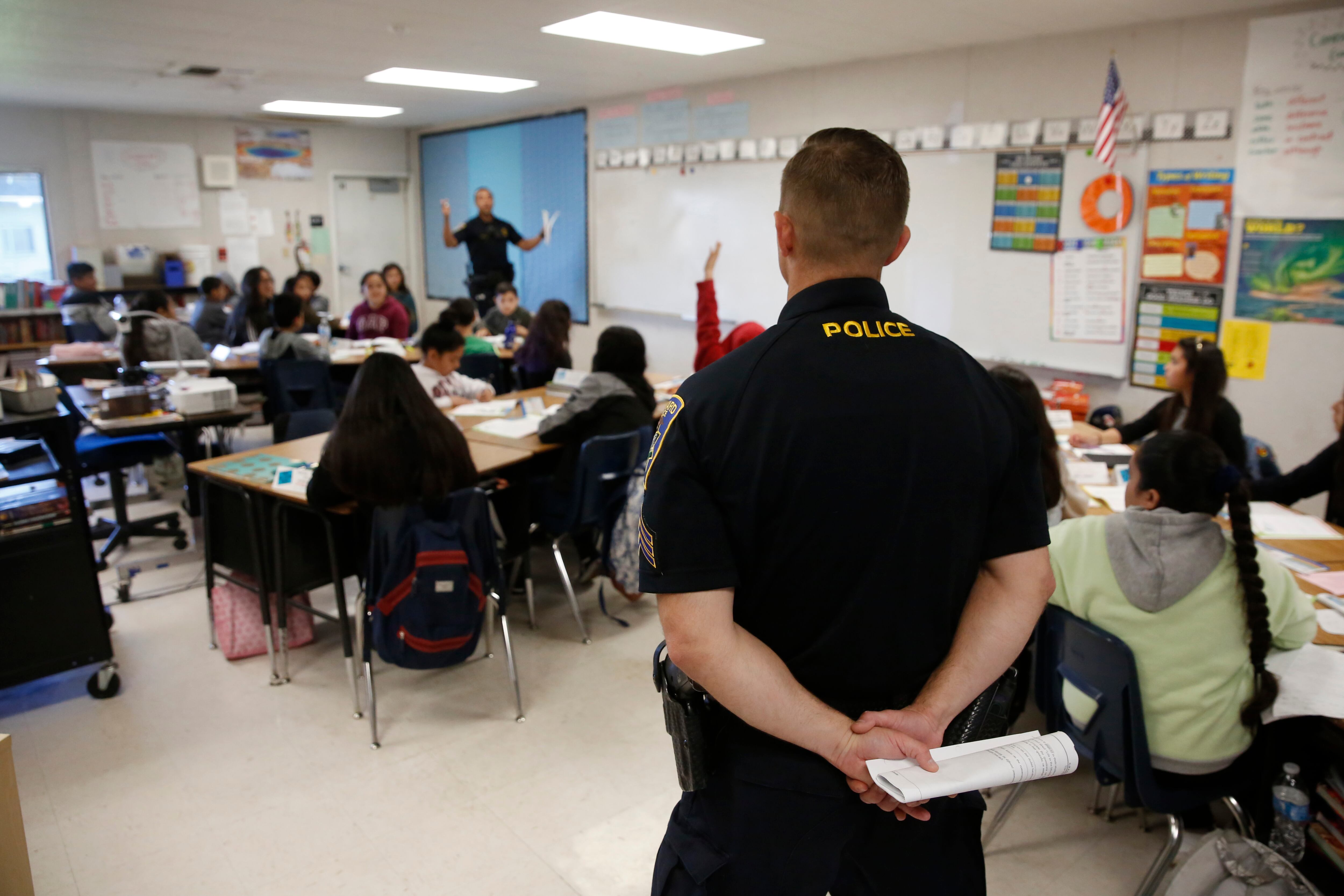

Per the agreement, Shelby County Schools will pay the Sheriff’s Office $50,000 for 36 deputies who will patrol assigned schools. The district also employs about 100 of its own school resource officers who are not governed by the agreement.

This year’s memorandum includes some changes, such as an additional 16 hours of training for school-based deputies and a job description that also includes mentoring students, fostering positive relationships with law enforcement, and de-escalating conflicts rather than funneling students into the criminal justice system.

After much discussion and several public comments, the board added an amendment requiring officers to follow all board policies — including refraining from interrogating students without parental consent, a concern many students and advocates have voiced over several months.

While the rule was already a district policy, board members demanded its inclusion in the formal agreement with the Sheriff’s Office, emphasizing that they appreciated the courage it took for student advocates to speak out their frustrations with policing in schools.

Board member Stephanie Love said the memorandum must reflect concerns students have expressed after months of board debate.

“On the outside looking in, it would appear that everyone has wasted their time because it’s just a simple MOU. Why couldn’t all of that have been included?” she asked before the amendment passed.

Board member Miska Clay Bibbs said documents should outlive and detail one-on-one conversations.

“We want to ensure the document reflects all of the conversations being had,” she said.

However, the contract doesn’t address all the concerns expressed by Memphis’ grassroots Counselors Not Cops campaign.

Paul Garner, who has spearheaded the movement, called the board’s action a “huge disappointment.” He said nothing of substance changed from the district’s last agreement with the Sheriff’s Office.

“They left so many of the valid concerns that youth and advocates have been bringing up for months unaddressed,” Garner said. “Essentially, they just voted to uphold the status quo and perpetuate the school-to-prison pipeline.”

As of Tuesday evening, over 1,300 community members had written letters to board members and administrators, demanding the district end its ties with the Sheriff’s Office in order to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline. The term refers to the likelihood that students of color and those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds will become entangled in the criminal justice system early in life and continue that burden into adulthood because of law enforcement presence in schools.

An April Brookings Institution report found that school policing criminalizes typical adolescent behavior, escalating cutting class to a truancy charge and graffiti on bathroom walls to a vandalism charge, for example. In addition, data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights shows that school resource officers are more than twice as likely to refer Black students for prosecution compared with their white peers.

Instead of spending $50,000 to have sheriff’s deputies patrolling schools, advocates urged the board to use the funds to add more counselors, social workers, nurses, and other staff to address mental health concerns and conflict resolution in schools.

In an interview Tuesday, student Zahra Chowdhury said she was inspired to advocate to remove law enforcement from schools after a friend told her about an experience she had with a school resource officer who handcuffed her in eighth grade because she got into an argument with another student.

“Counselors and psychologists and social workers are people who know how to work with youth,” said Chowdhury, a student representative with Memphis Interfaith Coalition for Action and Hope.

And more of them are needed, Chowdhury said. Fellow students often tell her that they either don’t know who their school counselor is, or they don’t feel comfortable asking overwhelmed counselors for help.

An ACLU report found that in 2015, schools in Shelby County, including other municipal districts, had 1 counselor for every 414 students — compared with the American School Counselor Association’s recommendation of 1 counselor for every 250 students.

While Superintendent Joris Ray said he, fellow administrators, and the board heard and appreciated community concerns about police in schools and increasing student mental health challenges, he highlighted the district’s recent focus on social and emotional learning.

Ray estimated the board has recently allocated about $100 million to mental health supports such as the expansion of the district’s ReSET rooms, designated classrooms for students to regroup after an argument or emotional outburst.

“I don’t think approving an MOU for $50,000 will interfere with that work,” Ray said. “I believe in keeping our students safe, and that’s not an ‘either or’ with social-emotional learning. We can do both.”