Bryan Johnson says few experiences prepared him to lead a school district during a pandemic, so he leaned on several principles that have served him well as a leader so far in his career.

Keep students at the center of all decisions. Listen to the experts on the ground. Never forget that you’re a public servant.

That ethos has helped Johnson become a leader among leaders in public education. This year, he represented Tennessee as one of four finalists for National Superintendent of the Year.

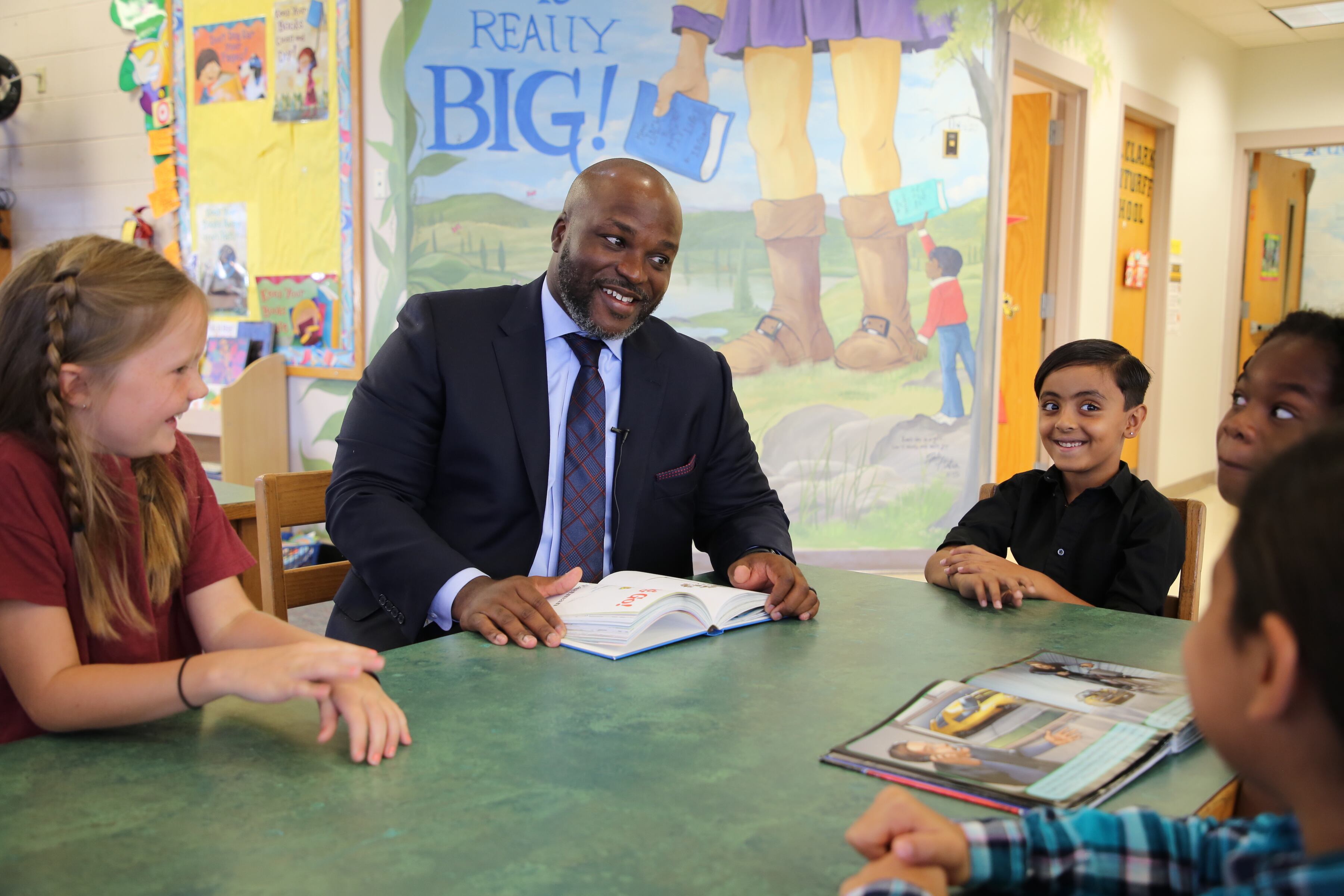

In four years at the helm of Chattanooga-based Hamilton County Schools, Johnson has shepherded student performance from the bottom to the top of Tennessee’s ranking system for academic growth. His district’s high school graduation rate has climbed for four straight years. And its number of schools designated below state expectations has dropped from nine to three.

In 2018, Johnson launched an initiative called Future Ready Institutes, placing 23 career academies in high schools to help students prepare for the jobs of tomorrow. To pay for the program, he secured over $3 million from local business and industry.

He also spearheaded a partnership with the local electric utility to provide broadband access for more than half of the school system’s 44,000-plus students, a third of whom opted to learn remotely during the pandemic and many considered economically disadvantaged.

Johnson’s pathway to leadership began with his own public education in Nashville and included stints as a teacher, principal, and chief academic officer in Clarksville, home to a U.S. military base on the border of Tennessee and Kentucky.

He spoke recently with Chalkbeat about his job, including ways to catch up students, helping children through a season of grief and trauma, and why no school day looks the same during a pandemic.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Had anything in your career prepared you for the challenges of leading a school district during a pandemic?

Each of my experiences in school leadership has helped to equip me, but this year has been unlike anything I’ve experienced in public education. I’ve relied on my commitment to public service to guide me during these difficult circumstances. When you focus on serving others, you can see beyond the personal stress that we’ve all felt.

How are you guiding your staff through this unprecedented time?

I’m trying to listen and respond to their needs. The “higher” your role, the more important it is to listen deeply to experts on the ground. We have established several feedback groups so we can hear directly from students, teachers, leaders, and the community. As always, we keep children at the forefront of all decisions.

What does a typical day look like for you now?

COVID-19 has taught me there is no such thing as typical. My day includes school visits, video calls, school board communication, COVID response, and meetings with local leaders. Because of the pandemic, I’ve had to become even more nimble and available to address the urgency of any given day.

How are you addressing learning gaps following months of remote learning?

Last summer, we offered programs for about 2,000 of our most at-risk learners, which gave us an opportunity to close some gaps and make adjustments for COVID prior to reopening in the fall. That experience helped us. Our district had 84 days of in-person learning during the first semester, and we’ve been on campus for the second semester since Feb. 1. We also ramped up our afterschool programming for intervention and enrichment and will expand our summer offerings.

After nearly a year of upheaval — and in some cases grief and trauma — are you doing anything different to account for what so many families have been through?

We know there are varying degrees of fear, anxiety, trauma, and uncertainty with regard to the virus, and that the COVID experience has not been uniform for every student and family in Hamilton County.

Last March, we set up a hotline in English and Spanish for families to call for any reason — from food and utilities to over-the-phone guidance from a school counselor for students. By the end of the summer, the hotline had fielded 1,500 calls.

This school year, we set up virtual learning centers in community spaces like the YMCA and local churches for families who opted their students out of in-person school but still needed support with virtual learning. Several of our community partners called remote students regularly to make sure they were engaging with online instruction and that their non-academic needs were being addressed.

We also began using a social-emotional learning screener from Panorama Education to identify areas of concern district-wide. And we launched “Wellness Wednesday” sessions to support the wellbeing of both teachers and students.

What inspired you to become an educator?

My parents were public servants. My mother was a social worker and caregiver, and my father was in the Navy and still serves as a pastor. Their emphasis on serving others and making an impact made a great impression on my siblings and me. Both of my parents were first-generation college attendees and elevated the importance of education in our home.

Describe your own experience as a student.

I grew up in Nashville and attended public schools from kindergarten until graduation. It was an amazing experience, and I remember many great teachers. Not only did I learn content and curriculum, they taught me about character, high expectations, and citizenship.

What’s the best leadership advice you received?

First, to always put students at the center of every decision you make as an educational leader. Second, to seek input whenever possible before making decisions. I’ve learned the decision is rarely, if ever, wrong when children are first in the decision-making process.

What’s one thing you’ve read that has made you a better educator?

Our senior leadership team is currently reading “The Infinite Game,” and one of the key themes is so appropriate in this season. The author, Simon Sinek, compares stability to resilience. Stable organizations weather the storm, he writes, while resilient organizations transform as a result of the storm.

What interactions with students, teachers, or principals inspire or affect you the most?

I try to be as visible as possible in schools. Seeing teachers, leaders and students in their everyday environment keeps me grounded on what matters most. I get to see great learning, teaching and leading on a regular basis, and it inspires me to continue to push. I also get to see collective efficacy in action as people like school nutrition workers and educational assistants work alongside teachers and leaders in support of children.

What gives you hope at this moment?

Our students have shown such resilience. And I’m inspired by the way our teachers have risen, challenged themselves, and sacrificed for children during this difficult season.