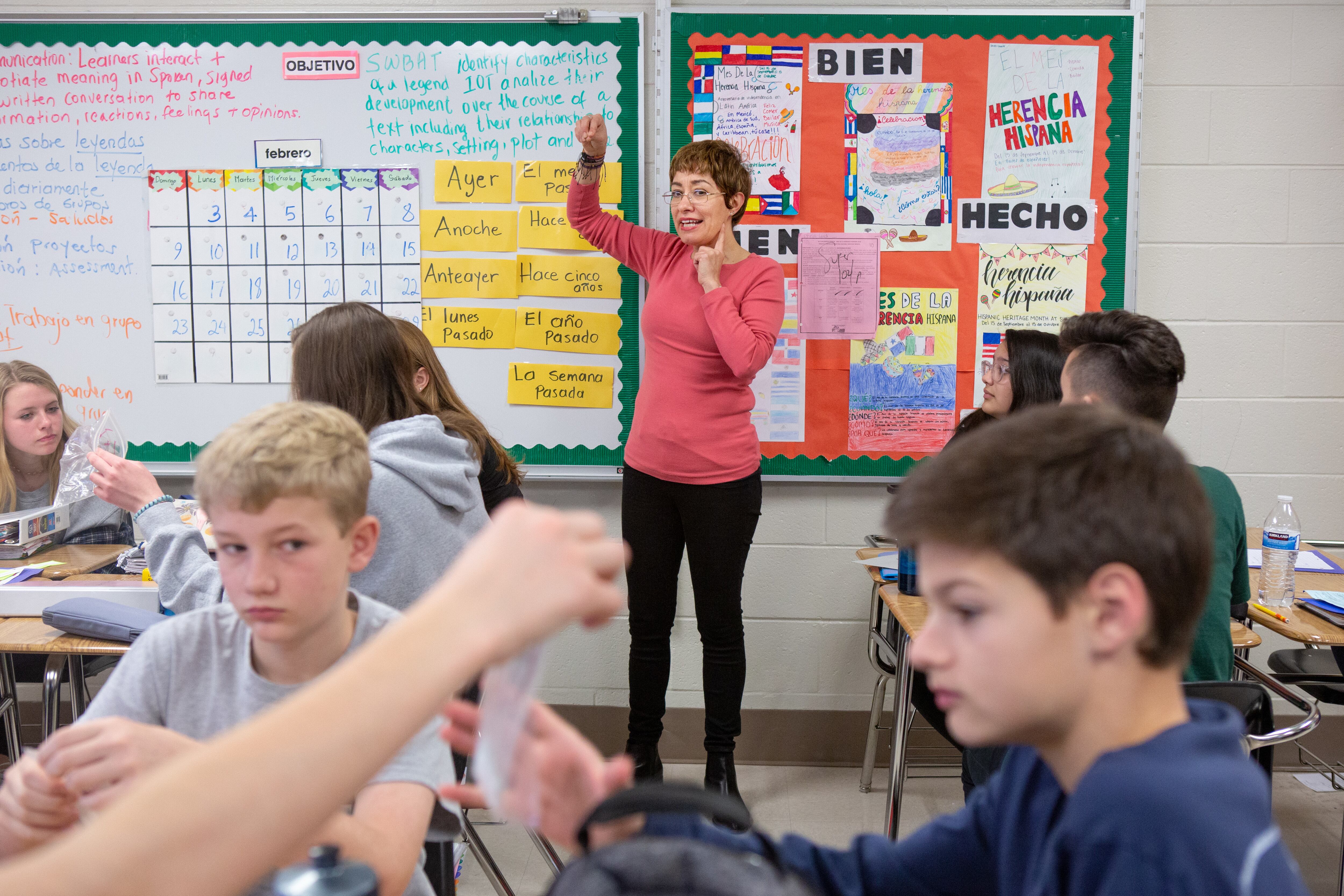

When teachers at Cherie Dennis’ school in Savannah, Georgia learned they were about to receive $1,000 bonuses, they were elated.

“It was such a challenging year,” said Dennis, who teaches students learning English as a second language at Hesse K-8 school and was the district’s teacher of the year. “To have that recognition from state officials of what teachers had been experiencing — there was such appreciation.”

Several states — including Georgia, Michigan, Florida, and Hawaii — and school districts have issued or are considering such “thank you” payments to teachers. The bonuses are meant as recognition for educators’ work through the pandemic — whether that included teaching in-person and virtually at the same time, dealing with frequent quarantines, or seeing their schedules repeatedly upended — and as a way of encouraging teachers to stick with the profession.

As the Hesse educators make clear, bonuses can boost morale. But the payments have also raised questions among researchers, some of whom argue that they’re unlikely to actually improve teacher retention — and kicked off a debate about whether such payments are a good use of federal stimulus funds.

“It is hard to imagine that using one-time money for thank you bonuses will be connected to either teacher retention or student achievement,” said Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the University of Washington.

“In the ideal, I would prefer that additional money that is spent on teachers is somehow tied in some way to improving outcomes for kids,” said Kirabo Jackson, a Northwestern University education economist.

The philosophical divide reflects different ways of thinking about schools, and about the billions in COVID relief being distributed by the federal government. To some, it’s critical that schools focus that money on efforts to help students directly. To others, schools are workplaces that need tools to keep staff members satisfied, and this helps students in the long run, too.

In states or districts that have opted for bonuses, they tend to be fairly modest, often around $1,000 per person. Many places say the funds will come from stimulus money meant to help schools respond to the COVID crisis, including by maintaining a stable workforce and addressing learning loss.

Although the thank you payments don’t clearly fall into one of the allowable uses for that money, recent guidance by the U.S. Department of Education indicates that such bonuses will likely be allowed, as long as they are “reasonable and necessary.”

Indeed, research has found that teacher churn generally harms students and that bonuses or higher pay can boost teacher retention. If the bonuses simply improve teacher morale, that could ultimately reduce attrition, too. And although teacher turnover doesn’t appear to have increased during the pandemic, there could be an uptick between this school year and next, since the economy has improved.

But some payments, including Georgia’s “retention bonus,” don’t appear designed to meaningfully improve teacher retention. That’s because money is going to all teachers in the middle of the school year, whether or not they plan to return to the classroom next year.

“Our worry is that using public funds in this way … misses an opportunity to structure the money to help the system meet the enormous challenges ahead on getting students up to speed,” said Marguerite Roza of Edunomics, a think tank tracking how schools are spending stimulus money.

A more effective strategy, some say, would be to provide the bonuses at the start of next school year rather than the middle of this year.

“You could essentially say, we’re going to provide these bonuses to anyone who was teaching this year who continues next year,” Jackson, whose work has found that more money can and often does improve school performance. “That would ensure people don’t leave and it shows appreciation in the same way.”

Margaret Ciccarelli, director of legislative affairs at the Professional Association of Georgia Educators, acknowledged that one-off mid-year payments aren’t likely to improve retention because most teachers leave during the summer. Lawmakers’ focus now, she said, should be longer-term investments in teacher pay to stem the tide of teachers leaving the classroom.

Still, Ciccarelli said, “We’ll happily take the money.”

Many districts are taking a different approach: tying additional pay to specific needs like teaching in high-needs areas or taking on extra duties to help students catch up. Detroit, for instance, is offering a recurring $15,000 bonus to teachers of students with disabilities, a perpetual shortage area. Numerous districts are beefing up summer school programs, and offering higher-than-usual pay to attract teachers to work over the summer.

But for some, the debate about retention misses the point. The bonuses are really about appreciation during a year when teachers have refashioned themselves, worked longer hours, and seen stress levels spike, they say.

“The intent was never to address retention,” said Sam Buchmeyer, a spokesperson for Grand Prairie school district outside Dallas, which used state money to issue $1,000 payments to all full-time school staff. “Our board was very vocal about wanting to do something right now to say ‘thank you’ and to do it in recognition of work already done.”

“Bottom line, I think teachers deserved it,” said Dennis, the Savannah teacher. “And I appreciate administrators and local and district and state officials saying we’ve heard what you have experienced this year, we hear your concerns, we see what you did, we understand how hard this was, and we appreciate you for it.”