My daughters and I were more than ready for this pandemic school year to end.

My two sixth graders were tired of the countless hours parked in front of a computer screen, tired of the nonstop cycle of Zoom classes, tired of hearing me badger them to finish their assignments.

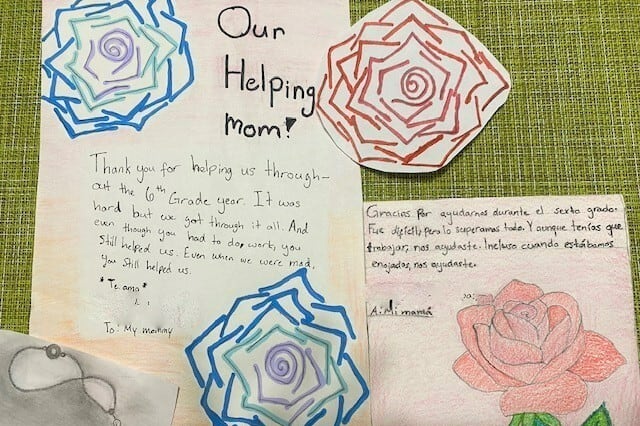

By the end of May, they had spent nearly 15 months sequestered at home, cut off from friends and the energizing social interaction of school. And I had spent nearly 15 months hovering over their shoulders, helping them untangle middle school math concepts I barely understood myself, nagging them to do their best on days when it was hard to get excited about learning from teachers they’ve never met in person.

We were bleary-eyed and bone-weary.

So, when they hit submit on their last online final exam and the 2020-21 school year was officially history, I expected an emotional release. Joy. Relief. Celebration.

The tears, however, caught me by surprise. They trickled down my cheeks as I congratulated my daughters on making it through an exhausting, soul-battering year. They kept coming as I wrapped them both in a bear hug, my thoughts flickering back over the previous 444 days, through the lockdown and virtual learning that began when their school abruptly shut down in the first wave of the pandemic.

I let myself cry, unleashing months of pent-up worry, frustration, and consternation — the fallout from grappling with a school system ill-equipped for the unprecedented crisis created by COVID-19.

Somehow, we had staggered to the finish line. But we didn’t emerge unscathed.

Nor have so many others who collided headlong into the school system this year: Families like mine who struggled — often unsuccessfully — to make virtual classes work. Parents who chose to send their children in-person after schools reopened. Teachers wrangling both Zoomies and roomies while worrying about their own health and safety. And kids trying to learn amid anxiety, grief, and isolation.

As districts around the country scrambled to translate bricks-and-mortar curriculum to virtual platforms and to balance health concerns with the pressure to reopen, the pandemic created new stumbling blocks for educators and families. It also magnified long-standing inequities in marginalized communities — the digital divide, funding imbalances, under-resourced schools, lack of mental health and trauma services — that too often stall the academic success of economically disadvantaged students and students of color.

Those disparities, brought into sharp relief by the pandemic, are the entrenched legacy of slavery, segregation, redlining, and systemic racism — barriers to equitable education that existed before COVID-19 became part of our vocabulary.

As an education reporter and a columnist, I had spent decades covering those issues and the impact on children and families. I followed a Mexican-American family in Massachusetts to illustrate the impact of the state’s decision to do away with bilingual education. I wrote about efforts to keep kids from dropping out of school in Camden, New Jersey, and the birth of that city’s charter school movement. I documented the many challenges facing the Houston school system: fear and disruption sown in Houston schools by anti-immigrant policies; a looming state takeover. And I examined unfair discipline practices that harm Black girls and push many out of school.

I also spent five years as a high school teacher in a suburban Houston district, where I witnessed the inequities play out daily in the classroom: Black students punished more often and more harshly than white classmates for dress code infractions. Predominantly white schools within the same district with better resources and equipment than campuses with more students of color. Curriculum and books that elided Black, Latino, Asian American, and Indigenous history and experience.

Now, as a story editor with Chalkbeat, I have joined a team of journalists with a mission to cover “one of America’s most important stories: the effort to improve schools for all children, especially those who have historically lacked access to a quality education.”

That mission is especially critical now, as schools and families navigate the bumpy road back to reopening. Over the last year, students have struggled to stay connected to teachers and to each other, many dropping off screens altogether. The chasm between families with the resources to get help and those who grind just to get enough to eat has grown even wider. More than 40,000 children have lost parents to COVID; countless others are grieving the deaths of other relatives and friends.

Others, like my daughters, are wrestling with the trauma of a lost year. And, in so many ways, they are among the lucky ones. As a former teacher with a masters in education, with a job that allowed me to work from home, I could be by their side, a de facto home school teacher guiding them through the trying, often tedious world of virtual learning.

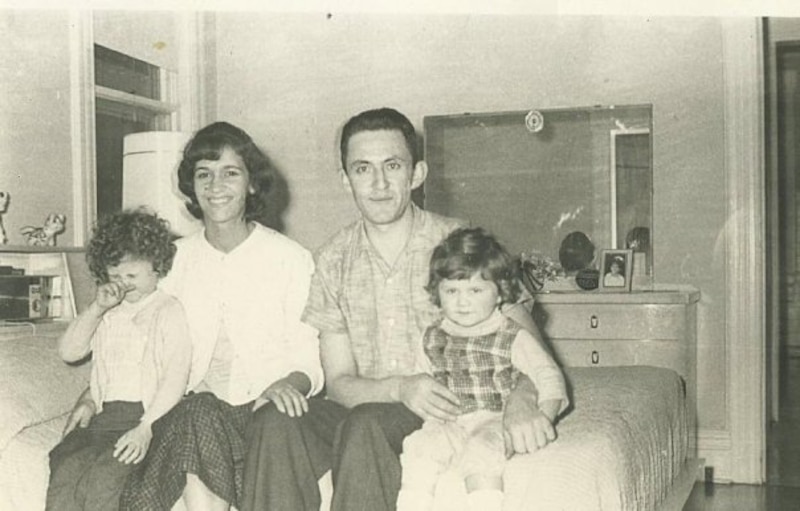

How, I often wondered, would my parents have weathered a year like this when I was in elementary school? When we were new immigrants still unravelling a new country, a second language, and an unfamiliar education system and they were working factory jobs that didn’t allow the freedom to stay at home?

Would I have been one of the kids holding on by a thread?

At Chalkbeat, the stories of families like my own — then and now — matter. Education equity matters. The voices of students, teachers, and parents matter.

That’s why I’m here.