There has been a substantial drop in the number of young children living in cities, portending even more punishing enrollment losses in urban schools across the country. That’s the jarring message of a new analysis examining population trends since the pandemic hit.

Cities across the country have already lost enrollment in their public schools, and this decline may well continue and even hasten in coming years. That might mean that urban districts face financial pressure to lay off teachers and close schools.

“The population data suggests that the shoe has yet to drop for K-12 school districts,” wrote researchers with the Economic Innovation Group, a bipartisan economic policy organization. “Today’s smaller crop of children under five will translate to lower K-12 enrollment in years to come.”

Using recent U.S. Census data, researchers Adam Ozimek and Connor O’Brien show that large urban counties were already seeing fewer young children before the pandemic hit — and then it got worse. Between the middle of 2020 and 2021, large urban areas experienced a 3.7% decline in children under 5 and a 1.1% dip in children between 5 and 17.

Expensive, high-demand areas saw even bigger drops. The number of children under 5 years old plummeted by 5.6% in Los Angeles County, 5.3% in Cook County (home of Chicago), and 9.5% in Manhattan. There were also substantial declines in school-age children in those cities, although they were less dramatic.

Reflecting this, urban school systems began seeing sharp enrollment drops — particularly in early grades — in the fall of 2020. While suburban and rural districts often gained back students in the most recent school year, cities typically continued losing enrollment. Private schools in some cities, including New York and Los Angeles, have also lost students since the pandemic (although more modestly than public schools).

The census data points to an underappreciated reason for this hollowing out: There are simply fewer children in big cities than previously. Inevitably, that means lower school enrollment.

“It’s not just that they switched schools; it’s that to some extent they left the community,” said Thomas Dee, a Stanford professor who has studied enrollment during the pandemic. “That just makes it all the more unlikely that these families are going to be returning.”

Families likely fled big cities after the pandemic hit for a number of reasons: loss of a job, a new ability to work remotely, fears of contracting COVID, and shuttered city amenities. Declining birth rates and lower immigration levels also likely play a role in the decline in the number of children. This underscores how schools are subject to the whims of economic and other factors that determine where families live.

The new analysis doesn’t examine the racial or economic demographics of families who have left cities. In New York City, enrollment declined in public schools of all types, but the drop was steeper in more affluent schools.

The approach of school systems themselves may have played a role in some families’ decisions to stay in or leave cities: Many urban districts began fall of 2020 fully virtual, and those places tended to see bigger enrollment fall offs — by roughly one percentage point — according to a study by Dee.

Notably, though, the fact that families with young children left at higher rates than those with school-age children suggests that existing connections with school communities may have kept some families in the city who otherwise might have left. During the pandemic, most parents have said their child’s school has done a good job.

The latest census data runs through July of 2021, so it’s possible that some families have returned to cities since then as COVID precautions have waned and job opportunities have grown. But high costs of living and remote work policies in some sectors may keep other families away. Some may have enrolled their children in schools elsewhere.

Indeed, many high-cost cities including New York, Los Angeles, and Denver, say they expect to continue to lose students in coming years. That would have major educational and financial consequences.

At the moment, still flush with federal relief, most city school systems do not have cash flow problems. This money is dwindling, though; the aid to schools must be budgeted by September 2024.

State funding for school districts is typically tied to enrollment, so fewer students means fewer dollars. There are also ominous signs of a recession, which could impact state aid.

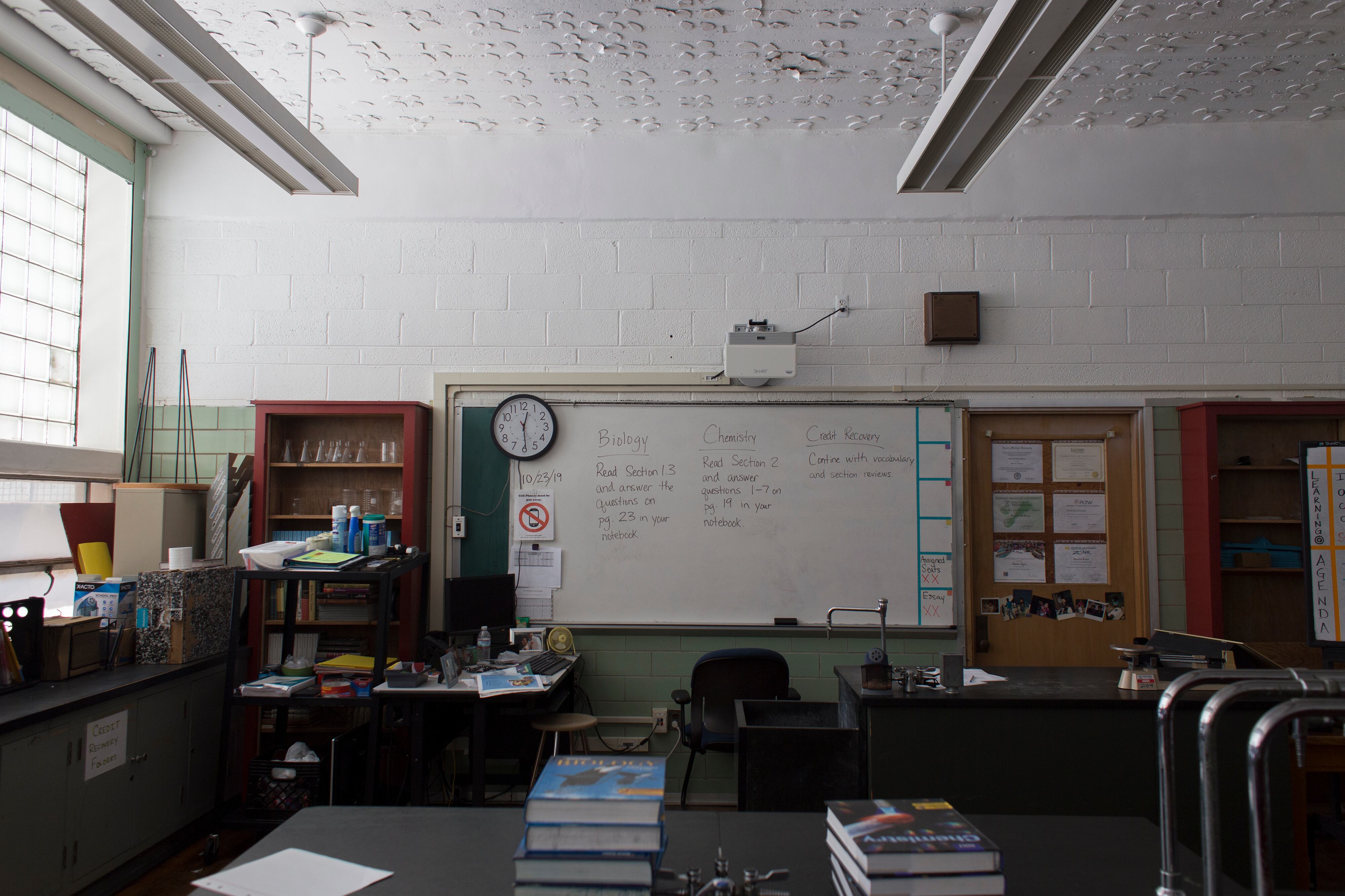

This confluence means that in coming years big-city districts could find themselves with less money, and fewer students spread across a hollowed out system of schools. That would mean under-enrolled schools that struggle to provide basic services and a glut of teachers and school staff that cities may not be able to afford.

“Districts are going to have to reckon with that,” said Dee. “You can already see some difficult and painful conversations happening.”

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.