With students off Zoom and back in classrooms, many schools have stopped helping students get online at home, new federal data shows.

Just 45% of public schools are providing home internet access to students who need it this school year, down from 70% earlier in the pandemic, according to August survey data released Tuesday by the National Center for Education Statistics.

The sharp decline in schools giving students Wi-Fi hotspots or covering the cost of home internet coincides with the end of widespread remote learning, first caused by school closures then by COVID quarantines. Yet even with schools fully reopened, students still are likely to need home internet for homework, sick days, temporary school shutdowns, virtual tutoring, and parent-teacher conferences.

And while home internet and device access expanded during the pandemic, 1 in 4 low-income families still did not have broadband internet at home a year after schools shut down, according to a 2021 survey. Instead many students had to put up with frustratingly slow internet speeds or work on their phones.

As recently as this spring, about a quarter of teenagers living in very low-income households said they sometimes can’t complete their homework because they don’t have reliable computer or internet access.

“I think there’s an inaccurate belief that more students and families actually have connectivity than actually do,” said D’Andre Weaver, chief digital equity officer at Digital Promise, a nonprofit focused on expanding student access to high-speed internet.

Weaver suspects that schools’ retreat from home internet assistance also reflects a new wariness of online learning based on the negative experiences had by many families and educators during the pandemic. But he argues that schools should try to improve online learning and expand internet access rather than turn away.

“Now it’s like, ‘Let’s throw the baby out with the bathwater,’” he said. “And that’s the wrong viewpoint.”

Just over 900 public schools participated in the survey, which was conducted August 9-23.

While less than half of schools said students will be provided with internet at home, 56% said students can get online at other locations, such as public libraries. Laptops and tablets appear to be much more readily available, with 94% of schools saying that students who need a digital device this academic year will be provided one.

Funding is another likely factor in schools’ scaling back support for home internet access. The federal stimulus money that school districts used to pay for hotspots and free internet plans is drying up, forcing schools to find other funding if they want to keep providing assistance.

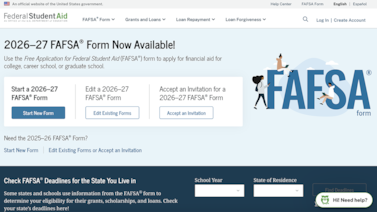

Also, the $1 trillion infrastructure bill that Congress passed last year included $14.2 billion for the Affordable Connectivity Program, which provides a monthly subsidy to help low-income families pay for internet service. Several major internet providers agreed to lower their prices so that the subsidy — up to $30 per month for most eligible households — would cover the full cost of a high-speed internet plan.

In a sense, the federal program removes schools as intermediaries by giving the internet subsidy directly to families. However, advocates say that schools still must support families who haven’t enrolled in the program or aren’t eligible.

New Jersey parent Nadirah Brown said she earns too much to receive the new subsidy but not enough to pay her more than $100 monthly internet bill without cutting other expenses.

“For the parents who don’t qualify, there is no program available for them,” she said, whose daughter is an eighth grader in a Newark public school.

The school lent her daughter a laptop and offered a Wi-Fi hotspot during remote learning, Brown said. But it did not offer either device this school year, even as teachers continue to assign homework that must be submitted online through Google Classroom, she added.

“It’s definitely still needed whether they’re working virtually or not,” she said about home internet.

A Newark Public Schools spokesperson did not immediately respond to emailed questions Monday.

In Newark, like many other cities, high-speed internet is widely available. The main problem is that many families cannot afford it, said Ronald Chaluisán, executive director of the Newark Trust for Education, a nonprofit whose mission includes promoting equitable internet access.

While they could benefit from the new federal subsidy, Chaluisán said many families are not aware of it. (Nationwide, less than 25% of eligible families enrolled in a previous iteration, called the Emergency Broadband Benefit.) Some families also struggle to complete the multi-step enrollment process, said Chaluisán, whose organization is partnering with the nonprofit Project Ready to spread awareness about the subsidy program.

He added that one lesson of remote learning is that every student needs a computer and internet access at home.

“They’re not luxury items,” he said. “They’re just necessities.”

Patrick Wall is a senior reporter covering national education issues. Contact him at pwall@chalkbeat.org.