Many schools struggle to find teachers, and many teachers struggle with student loan debt.

So the federal government’s long-running Teacher Loan Forgiveness program seems like a win–win.

But new research suggests that the federal government’s educator debt forgiveness program is not keeping teachers in the classroom and probably isn’t attracting new ones either. Researchers say the program’s complexity limits its reach, and few teachers take advantage of it each year. The bottom line: One of the few tools that the federal government has deployed to combat teacher shortages doesn’t seem to be making much of a difference.

This disappointing finding comes as the pandemic-era pause on federal student loan payments expires in the fall, while many schools have faced crippling teacher shortages.

“The program has really good intentions,” said Brian Jacob, a professor at the University of Michigan and coauthor of the study. But, ultimately, “it’s not effective as it’s currently structured.”

Loan forgiveness does not help retain teachers.

The Teacher Loan Forgiveness program, established in 1998, does exactly what its name says: forgives a chunk of federal student loan debt for public school teachers. This applies to those who teach for five consecutive years in a low- or moderate-income school. The baseline forgiveness amount is $5,000. But for those who teach in chronic shortage areas — science, math, and special education — that figure jumps to $17,500.

This should be appealing to new teachers, many of whom enter the classroom with significant debt. And, in theory, this perk should help schools attract and retain teachers.

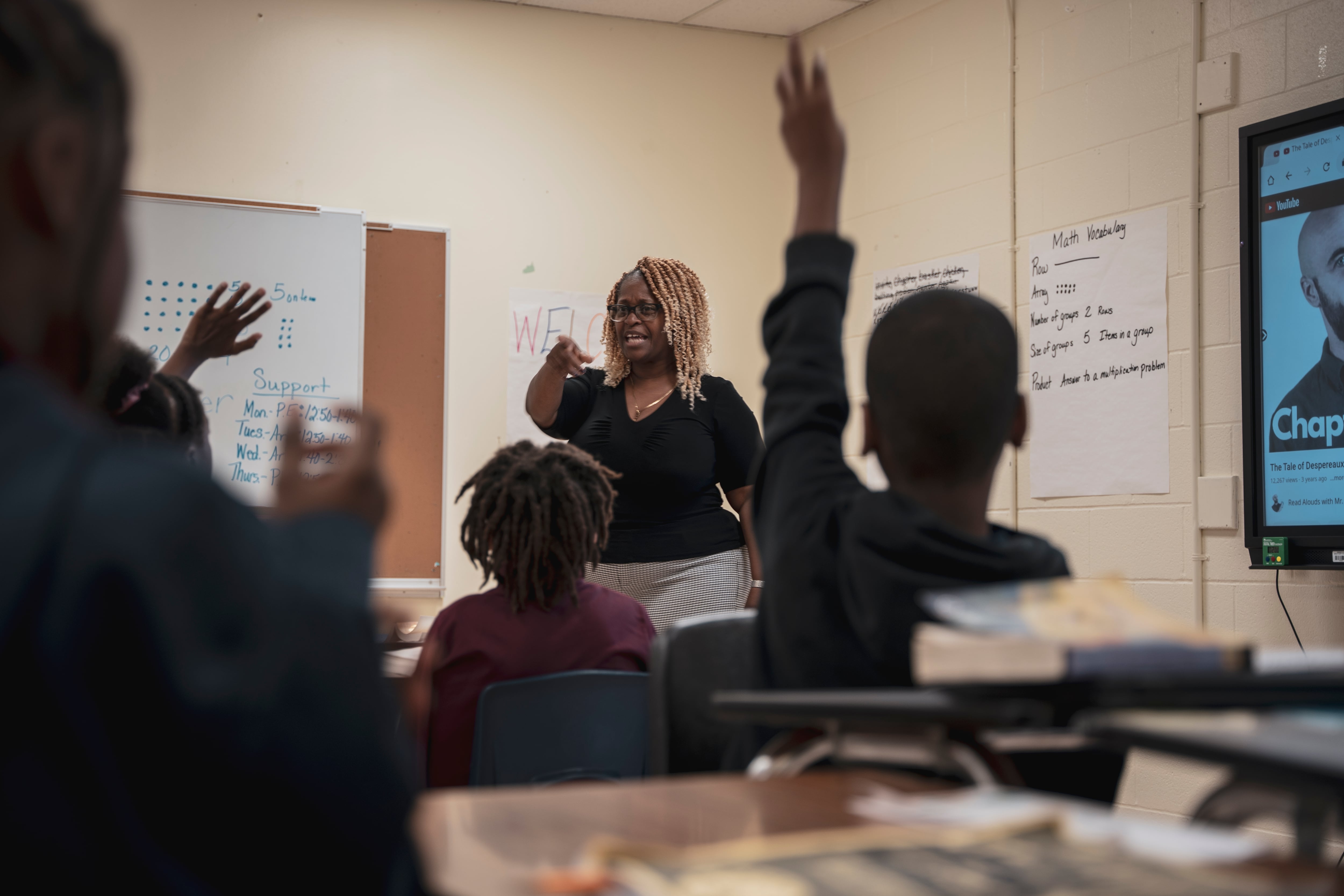

Jacob, along with Damon Jones at the University of Chicago and Benjamin Keys at the University of Pennsylvania, decided to test this theory. They compared schools in Michigan on each side of the eligibility threshold that allows teachers’ loans to be forgiven. Eligible schools were those where 30% of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch, a proxy for poverty. If the program was working, those schools should have had a leg up in getting teachers.

That’s not what the researchers found, though.

Eligible schools didn’t have a higher teacher retention rate. They also didn’t seem to be able to recruit better teachers (though this couldn’t be measured as precisely). A separate study from four other states produced similar non-results.

“The teachers in schools where they would have qualified for loan forgiveness, their patterns of retention or attrition or mobility, were exactly the same,” said Jacob.

But why? The researchers considered a range of options.

Could it be that the loan forgiveness amounts weren’t large enough? Or that financial incentives just aren’t appealing to teachers? Probably not. Prior research has found that even small bonuses can help keep teachers in the classroom.

Perhaps teachers just don’t value loan relief that much? But the researchers conducted a survey experiment showing that teachers say they would be more likely to work at a school that offered debt forgiveness. In fact, they value a loan write-off nearly as much as a cash bonus.

Maybe teachers just don’t know about the program? That could be part of it. In a survey, only 38% of teachers with loan debt said they were very aware of the Teacher Loan Forgiveness programs rules. Most could not correctly answer how many years it took to be eligible for forgiveness.

So researchers sent a select group of teachers mailers informing them of the program and even offered help applying by phone. But that still didn’t move the needle on teacher retention.

“The information alone, or the information with a little bit of assistance, wasn’t enough,” Jacob said.

Complexity, bureaucracy may derail program

To receive forgiveness, a teacher has to know about the program, meet the precise eligibility standards, get a school administrator to submit paperwork, and work with their loan provider to enroll. Each step of the process, while certainly doable, could trip up an applicant. It could make the potential benefits less salient when choosing where or whether to teach. It might even stop some teachers from getting the benefit at all.

“Our research team, highly motivated to encourage take-up of the program, struggled to find clear guidelines on how to navigate the enrollment process,” the study says. For instance, when researchers called loan providers, representatives often did not know details of the program.

Trying to provide teachers with accurate information about the program also proved challenging. In focus groups, teachers described “a lack of trust in offers that sound too good to be true, in some cases doubting the promises laid out in the outreach materials our research team developed,” the study explained.

The researchers suggest simplifying and streamlining the process as much as possible. “Our results suggest that if any future loan forgiveness program is implemented in the U.S., ease of application and eligibility determination may be key to achieving broad participation,” they write.

One other potential explanation for the disappointing results is that teachers have another option to get their loans wiped out: Public Service Loan Forgiveness, an alternative program available to those working in government or nonprofits. This option may be more appealing to some teachers because it will eventually forgive all remaining loan debt. Unlike the teacher-focused forgiveness, though, it only applies after 10 years rather than five.

What’s clear is that relatively few teachers take advantage of Teacher Loan Forgiveness each year. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Education reported that 32,000 teachers received forgiveness through the program. This is a small fraction of teachers who have student loan debt, although it’s not clear how many would have been eligible for Teacher Loan Forgiveness. In 2015, the Government Accountability Office warned that “awareness among potential participants continues to be a challenge.” More recently, the Department of Education noted that it “is working on ways to raise awareness among current and incoming students.”

This is not the only federal teacher shortage program that has been beset with bureaucratic challenges. TEACH Grants help fund the education of aspiring teachers. The grants must be paid back by those who do not teach in low-income schools for at least four years. However, NPR reported in 2018 that paperwork snafus left thousands of teachers who should have benefitted from the program with substantial debt. In 2021, the Department of Education announced an overhaul to protect teachers from having grants unfairly converted into loans.

Meanwhile, student loan debt is likely on many teachers’ minds these days: the U.S. Supreme Court recently struck down the Biden administration’s plan to cancel $10,000 worth of federal student loan debt and the pause of loan payments is coming to end this October.

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.