Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

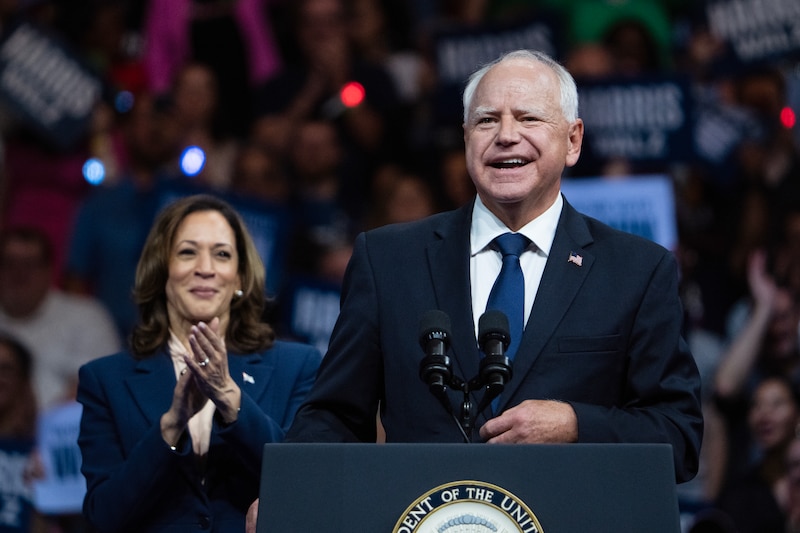

The photos have emerged as perhaps the most iconic image of Tim Walz.

The Minnesota governor and longtime high school teacher had just signed into law a bill making school breakfast and lunch free to nearly all children in the state. In the pictures from last year, Walz is surrounded by children who happily embrace him, and he beams with joy.

Teachers and teachers unions have embraced Walz as the Democrats’ vice presidential nominee with similar joy. The last major party candidate to previously have led a K-12 classroom was Lyndon B. Johnson.

And they say they’re excited about not just his background but his record.

As governor, Walz focused on providing schools with more money and resources, addressing the affordability of child care and college, and working to reduce child poverty. Walz has connected these policy priorities to his time in the classroom, and Democrats increasingly have embraced them as the solution to what ails public education.

This emphasis on resources and social factors outside the classroom sidesteps education issues that have divided Democrats and differs in key respects from former President Barack Obama’s tenure, when Democrats backed education reform policies like merit pay for teachers and pushed low-performing schools to improve or face closure. It stands in even sharper contrast to Republican attacks on public schools as places where children are at risk of indoctrination.

Critics of the Walz pick say it reflects Harris’ deference to teachers unions and likely closes the door on any major push to improve school performance through federal policy. But many political observers say Walz represents a chance for Democrats to embrace a positive vision of public schools and the teaching profession, after several years in which conservatives claiming to represent parents’ rights have largely driven education politics.

“It feels like an opportunity to turn the page on the way education has been discussed for the last few years,” said Jon Valant, who heads the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. “Democrats have been reluctant to engage on some of these issues, and now we’ll have someone on the forefront who is very natural and compelling when he talks about it.”

Walz’ ability to listen and respond to what he hears by working for solutions has struck Joe Nathan, who heads Minnesota’s Center for School Change and has worked on education policy and charter school issues in the state for years.

One example that stands out to Nathan emerged from the aftermath of pandemic disruptions. When many businesses shuttered in 2020, Minnesota at first issued unemployment benefits to some teenagers who applied. But then, citing a 1939 law, the state tried to take back thousands of dollars that, for students from low-income families, had already gone to rent and utility bills. To qualify for assistance, the students would need to drop out of high school, curtailing their education to help parents and siblings.

Students organized and successfully sued the state, then worked to change the law. Walz met with the students and became an ally in their cause.

“It’s a very rare politician who listens to kids and says ‘you’re right’ and then does something,” Nathan said.

Why Walz resonates with teachers and students

Since Walz became Harris’ running mate, stories have poured out from former students who’ve described how Walz connected with them when other teachers couldn’t, how he noticed something they were trying to say, or stood up for them. Yes, he coached Mankato West’s winless football team to a state championship, “but he was a pretty great coach even when we weren’t winning,” one former player told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune.

“We’ve all had that teacher. We’ve all known that teacher,” said Mark Sass, a retired high social studies teacher in Colorado. “That’s very relatable.”

Teachers respond to Walz on yet another level, said Sass, who serves as policy director for Teach Plus Colorado and works every year with cohorts of teachers doing policy research.

“They feel like there’s somebody who’s been through this, and they feel like there is someone who will go in and fight for them,” he said. “And it will be interesting to see what happens. There’s a difference between fighting for the teachers and fighting for the kids.”

It’s rare for someone with extensive classroom experience to have such a seat at the table where decisions get made, said Jal Mehta, a Harvard education professor.

“Teachers feel really excited that they might have one of their own in the White House,” he said.

It might also appeal to voters in general. Poll after poll finds that large majorities of parents like their kids’ teachers, said Jennifer Berkshire, an education researcher and author of the book “The Education Wars.”

“That is the mainstream view, and Walz reminds us of that,” she said.

That excitement could yield benefits beyond the campaign trail. Teachers report working longer hours for less pay than their peers who also do jobs that require college degrees. Teacher turnover is high. Polls find that most parents wouldn’t want their children to enter the teaching profession.

Harris campaigned on raising teacher pay back in 2019, and the federal government could leverage its money to improve pay and working conditions, Mehta said. But he also noted that at their first rally together in Philadelphia, Walz thanked Harris for “bringing back the joy” to the campaign.

“We’re also missing a lot of joy in the classroom, and they could channel that joy into how they talk about schools,” Mehta said. “If it’s just that and no policy proposals, it will feel light after a while, but the combination of the rhetoric and some policy could be really invigorating for the teaching profession.”

Walz not shying away from culture war issues

A key point in Walz’s biography is that he served as the first faculty advisor to Mankato West’s Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA). Such clubs were once controversial, and Walz thought it was important that a straight married military veteran who coached the football team take on that role.

GSAs, now more commonly known as Gender and Sexuality Alliances, are federally protected under the same law that allows Bible study groups to meet on school grounds. But they’re under renewed scrutiny as Republican-led states pass laws restricting how teachers talk about gender and sexuality at school or what books students have access to.

With Democrats already taking the blame for extended school closures and mask mandates that were unpopular with some parents, they were slow to respond to the conservative parents’ rights movement to a certain extent.

But as governor, with the help of a supportive legislature, Walz has tackled so-called culture war issues head on instead of evading them. He made Minnesota a “trans refuge” state for people fleeing restrictive laws, banned book bans, and expanded ethnic studies and Indigenous history.

Related: In Tim Walz, many teachers see themselves — and an opportunity

These issues could be front and center in a future Trump administration. The Republican platform calls for removing federal funding for schools teaching “inappropriate” lessons on race and history, and for rolling back new Title IX rules that expand protections for LGBTQ students and staff. Already, Republican-led states have sued to block implementation of the Title IX rules.

Conservative parent groups were quick to blast Walz. On Fox and Friends, Moms for Liberty co-founder Tiffany Justice called him “the most anti-parent candidate that Kamala Harris could have chosen.”

Some Republicans have mocked Walz as “Tampon Tim” for backing a law that requires schools to make period products available at no charge to all menstruating students in the restrooms they regularly use. The law’s wording covers transgender boys who use the boys’ restroom.

If Walz were a teacher today stepping up to sponsor his school’s GSA, Berkshire said, the GOP would “demonize him as a groomer” and then argue: “This is why we don’t need schools, and we should have education savings accounts.”

Walz helps Democrats link public schools, family policy

Johnson’s time teaching impoverished students in South Texas influenced his Great Society initiatives, which significantly expanded the social safety net, said Kal Alston, professor at Syracuse University’s school of education. Johnson also spoke up for the value of public school as a place where people from different backgrounds come together in common purpose.

“He spoke from the White House about how being a teacher really shaped his view of the opportunities that came to him from attending public school,” Alston said.

Similarly, Walz’s “experience in the classroom may have informed why he thought it was important that kids not come into the classroom hungry,” said Sass, the retired Colorado teacher. “He understood the impacts that economic conditions can have on student achievement, and it seems like he took that to heart when he became governor.”

Cole Stevens was one of the Minnesota students who faced the loss of unemployment benefits back in 2020. He said Walz’s administration encouraged students to hold the line on their priority, which was ensuring that students were treated just like other workers whose employers had paid into the state’s unemployment fund.

Stevens, now the director of impact at Bridgemakers, a youth-led organization he co-founded, said he appreciated that Walz took young people seriously and didn’t patronize them. Stevens, who was speaking for himself and not for Bridgemakers, hopes that Walz takes that approach to Washington and helps find bipartisan solutions to education problems.

“Our schools are still not effective as a whole,” he said. “If you live in a low-income ZIP code, your whole life trajectory is determined at that point. We need to fund schools differently. We need to hold schools accountable in different ways, with more practical skills for youth and more personalized learning opportunities for students to unlock their full potential.”

Few observers expect substantive K-12 policy to come out of the federal government any time soon, though there is work to be done. Pandemic recovery is woefully incomplete even as federal COVID assistance is expiring. The Every Student Succeeds Act, which is supposed to hold schools accountable for student achievement, is overdue for reauthorization. So is the federal law that governs special education but provides a fraction of the promised funding.

Policy on charter schools, which are publicly funded but independently run, is also in flux. Once embraced by many Democrats, charter schools have not found the same kind of support in the Biden administration. But Nathan, the Minnesota education advocate who helped pass the state’s first-in-the-nation charter school law in 1991, said he’s always found Walz to be “fair-minded” and that the governor ensured charter schools shared in increased school funding.

“There is no question he is a very strong union guy and a very strong public education guy, but he is also fair-minded,” Nathan said. “He understands charter schools are part of the public school system, and he understands that a significant percentage of charter school students are low-income students of color.”

Walz’s emphasis on child poverty, wraparound services, and increasing resources for schools aligns with Harris’ “care economy” agenda that focuses on child care, elder care, and family leave. Valant, of the Brookings Institution, said Democrats for too long ceded the language of “parents’ rights” to conservatives, while Walz’s approach offers a new way of talking about building education systems that meet parents’ needs.

Making that case might have been more complicated had Harris picked Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro. A top contender for the VP slot, Shapiro last year publicly backed vouchers; Republicans have made school choice a crucial part of their education platform.

Having Shapiro on the ticket would have elevated “a candidate who makes the same argument that Republicans are making” when “we’re having this key debate about whether we should have public schools,” Berkshire said. It also would have upset key constituencies, like the two national teachers unions. But that calculation is one reason Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute, was disappointed Harris chose Walz.

“People would say, ‘Wow, she showed some real courage in breaking with some parts of her base,’” he said. “That doesn’t mean a Harris-Shapiro administration would have promoted private school choice. But it would have been an important indicator she was really fighting for the center.”

In Walz, Petrilli said he sees “a lot of love for kids, and that’s great, but I don’t see any tough love for schools that are doing a poor job.”

A decade ago, Democratic candidates might have been talking about test scores and charter schools, Berkshire said, but no longer: “We’re not going to hear that. We’re going to hear the prairie populist argument for public schools.”

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.