Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Roughly half of middle and high schoolers report losing interest in math class at least half the time, and 1 in 10 lack interest nearly all the time during class, a new study shows.

In addition, the students who felt the most disengaged in math class said they wanted fewer online activities and more real-world applications in their math classes.

Those and other findings published Tuesday from the research corporation RAND highlight several ongoing challenges for instruction in math, where nationwide student achievement has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels and the gap between the highest and lowest-performing students in math has continued to grow.

Feeling bored in math class from time to time is not an unusual experience, and feeling “math anxiety” is common. However, the RAND study notes that routine boredom is associated with lower school performance, reduced motivation, reduced effort, and increased rates of dropping out of school.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study found that the students who are the most likely to maintain their interest in math comprehend math, feel supported in math, are confident in their ability to do well in math, enjoy math, believe in the need to learn math, and see themselves as a “math person.”

Dr. Heather Schwartz, a RAND researcher and the primary investigator of the study, noted that the middle and high school years are when students end up on advanced or regular math tracks. Schwartz said that for young students determining their own sense of math ability, “Tracking programs can be a form of external messaging.”

Nearly all the students who said they identified as a “math person” came to that conclusion before they reached high school, the RAND survey results show. A majority of those students identified that way as early as elementary school. In contrast, nearly a third of students surveyed said they never identified that way.

“Math ability is malleable way past middle school,” Schwartz said. Yet, she noted that the survey indicates students’ perception of their own capabilities often remains static.

The RAND study drew on data from their newly established American Youth Panel, a nationally representative survey of students ages 12-21. It used survey responses of 434 students in grades 5-12. Because this was the first survey sent to members of the panel, there is no comparable data on student math interest prior to the pandemic, so it doesn’t measure any change in student interest.

The RAND study found that 26% percent of students in middle and high school reported losing interest during a majority of their math lessons. On the other end of the spectrum, a quarter of students said they never or almost never lost interest in math class.

There weren’t major differences in the findings across key demographic groups: Students in middle and high school, boys and girls, and students of different races and ethnicities reported feeling bored during a majority of math class at similar rates.

Dr. Janine Remillard, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education and expert in mathematics curriculum, said that in many math classes, “It’s usually four or five students answering all the questions, and then the kids who either don’t understand or are less interested or just take a little bit more time — they just zone out.”

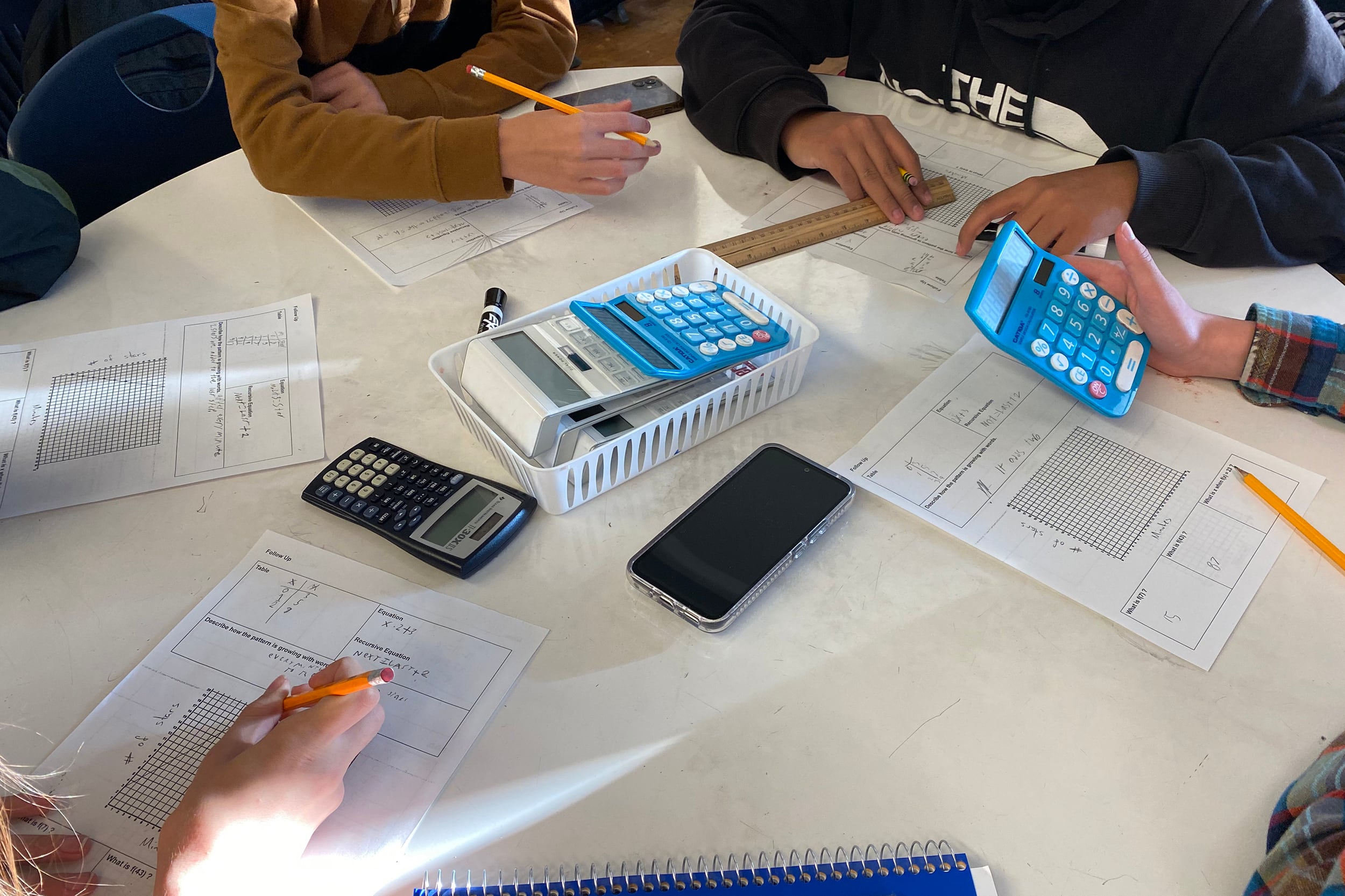

Over 50% of students who lost interest in almost all of their math classes asked for fewer online activities and more real-world problems, the RAND study shows. Schwartz hypothesizes that some online math programs represent a “modern worksheet” and emphasize solo work and repetition. Students who are bored in class instead crave face-to-face activities that focus on application, she said.

During Remillard’s math teacher training classes, she puts students in her math teacher training class into groups to solve math problems. But she doesn’t tell them what strategy to use.

The students are forced to work together in order to understand the process of finding an answer rather than simply repeating a given formula. All of her students typically say that if they had learned math this way, they would think of themselves as a math person, according to Remillard, who was not involved in the RAND study.

Norah Rami is a Dow Jones education reporting intern on Chalkbeat’s national desk. Reach Norah at nrami@chalkbeat.org.