Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

The Grandview school district’s headquarters is nearly 1,000 miles away from the White House. Yet President Donald Trump keeps taking up Kenny Rodrequez’s brain power.

Rodrequez, who leads the 4,000-student district south of Kansas City, Missouri, has never before been asked so many questions by so many people in his community about federal education policy. He reads every Trump executive order closely so he can make sure his board members know what they mean, and what they don’t.

Every aspect of running the district is more complicated. Planning something as simple as back-to-school registration takes longer because Trump’s aggressive immigration enforcement has made parents afraid to come to evening events. Planning next year’s budget is tricky too. Federal funds no longer feel reliable.

And Rodrequez chooses his words carefully when he’s talking to colleagues or lawmakers from conservative parts of Missouri who might control state education policy.

“I’m not going to wear my equity shirt everywhere,” he said.

But has anything changed in Grandview classrooms? Something that students or parents might notice? Not really, Rodrequez said. Not yet anyway.

Critics and allies alike say they’ve been stunned by the speed at which Trump has moved to enact an education agenda that was a secondary concern, at best, on the campaign trail. He’s launched the most serious attempt in 40 years to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education. He’s hollowed out the offices responsible for traditional federal roles like research and civil rights protection. He’s cancelled hundreds of millions of dollars for teacher training, pandemic recovery, and STEM education.

Even as Trump has continued to make public promises to return education to the states, he’s deployed the full power of the federal government, sometimes in new and legally questionable ways, to pressure states and school districts to comply with his agenda. But five months into Trump’s second term, much of that agenda is tied up in lawsuits and preliminary injunctions, leaving its future uncertain.

Some observers say Trump is washing his hands of core federal duties that protect vulnerable children while marshalling a calculated attack on public education that will reverberate for years. Others say Trump deliberately unleashed chaos to shatter an entrenched bureaucracy that, at best, did little to support schools’ core mission. Educators, meanwhile, are bracing for impact and thinking about their jobs in new ways.

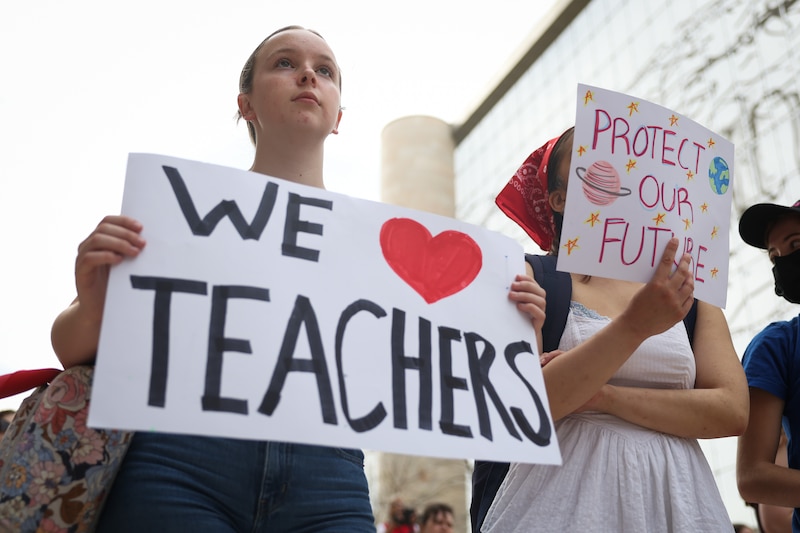

Teachers walk a line as Trump targets DEI

Trump promised to get “woke” out of American schools. In this vein, his executive orders have targeted diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, restorative justice programs, curriculum that suggests the United States has racist origins, and especially protections for transgender students.

The administration has tried to use funding as leverage. The Education Department took the unprecedented step of trying to strip Maine of its federal funding because it allows transgender girls to compete on girls’ sports teams, and it launched a Title IX special investigations unit with the Justice Department.

The Education Department touted this and other actions as standing up for women and girls and a highlight of Trump’s first 100 days in office. Many transgender students, meanwhile, report an increase in bullying and harassment.

The department told state and district leaders that programs associated with DEI may actually be illegal discrimination. Those include mentorship programs for students and teachers of color and magnet school admissions policies that aim to diversify the student body. Schools that use such strategies are risking billions in federal funding, the department asserted. Many legal experts say this interpretation of the law is incorrect, and federal judges have paused enforcement. But the Education Department continues to open new civil rights investigations based on that view, which it outlined in a Dear Colleague letter.

In fact, federal civil rights enforcement priorities have changed dramatically. ProPublica reported that under Trump the Office for Civil Rights has dropped ongoing investigations into serious racial bullying and mistreatment of students with disabilities and abandoned agreements that required school districts to change how they treated Native students.

And the U.S. DOGE Service’s efforts to root out alleged waste, fraud, and abuse targeted work that officials deemed supportive of DEI.

“We do believe that the Dear Colleague letter puts a target on districts that are supporting our work and puts a target on organizations like ours,” said Sharif El-Mekki, founder and CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, which works to diversify the teaching workforce. The center joined teachers unions and civil liberties groups in suing the administration.

Some communities have rushed to comply, either exercising an abundance of caution or sensing an opportunity.

District administrators ordered an Idaho teacher to remove an “Everyone is Welcome Here” sign. A Colorado school district is considering ending discrimination protections for LGBTQ students and staff. An Iowa district backed out of a long-running event that promoted reading Black authors even as other school districts maintained their participation. An Indiana school district ended an incentive program for “minority and local business participation.”

Nicole Neily, founder and president of Defending Education, a conservative parent group, predicted on a recent American Enterprise Institute panel that the Trump administration’s legacy will be “four years of the back of the DEI movement being broken.”

Educators told Chalkbeat they notice shifts even in districts that have not formally changed their policies. The pressure feels more acute in red states, where public sentiment and local laws are more aligned with the Trump administration.

“There is a lot of fear about saying something and losing your job or having to visit the Office of Professional Standards or having a parent complain about you,” said Florida teacher Renée O’Brien.

She no longer feels comfortable inviting students in her argument and persuasion class to discuss and write about politics and current events.

In Indiana, where state leaders have been eager to comply with Trump administration directives, junior high principal Jim Bever hesitates to tout the social-emotional learning interventions that have led to fewer suspensions and expulsions, greater parent and student satisfaction, and fewer violent outbursts from students.

“We have reams of data about positive outcomes, but we can’t talk about social and emotional learning now,” Bever said.

That’s because it has been swept up in national as well as state attacks on DEI, he said, even though the two concepts are completely different.

But to some, the Trump-driven changes aren’t coming fast enough. Priscilla Rahn, a Denver teacher who has been active in Colorado Republican Party politics, said her district still uses language such as “dismantling systems of white supremacy” while she sees little evidence that it’s made schools better.

“We do all these DEI trainings, and our kids still can’t read and write on grade level,” she said. “We still have a 30-percentage-point gap between Black and white students. It isn’t working.”

Some Trump education moves not on ‘bingo card’

The frenzy of federal activity has slowed. It’s unclear if the Trump education agenda is set or whether there is more to come, especially as Education Secretary Linda McMahon and her top deputies settle into their roles. But the rapid changes have created unease and confusion in ways that defy easy ideological categories.

Some conservatives question the expansion of federal power. Some education reformers who traditionally backed Democrats wonder whether some good might come from shaking up the status quo.

The Education Department has only about half the staff it had at the end of the Biden administration, raising questions about how the department will carry out key functions. Education advocacy groups, teachers unions, and Democratic politicians have led the backlash. Yet even conservatives like Neily who support the president’s agenda worry the cuts are so deep, especially in the Office for Civil Rights, that the administration will struggle to carry out its own priorities.

The Trump administration’s battle with Maine could upend school funding and the relationship between the states and the federal government. Or Maine could prevail. But the Trump administration may see political upside to having the confrontation — exacting a price for defiance and scoring points in the court of public opinion.

“I would be very surprised if Maine schools don’t end up getting their Title I money, but at the same time I think these are fights the administration is happy to have,” said Michael Petrilli of the center-right Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “Certainly on the trans sports issue, the public is overwhelmingly on the side of the administration.”

Sometimes the administration seems to be testing the waters to see which ideas generate the most pushback from constituencies they care about. Parents of students with disabilities objected loudly when Trump suggested moving special education oversight to the Department of Health and Human Services. That proposal doesn’t seem to be moving forward — at least not yet. Transgender young people don’t have the same kind of longstanding political capital.

Neither do education researchers, who often are affiliated with the same higher education institutions targeted by the Trump administration. But education research itself is valued across the political spectrum.

That made the decision to eviscerate the Institute of Education Sciences, a congressionally mandated office that oversees research, especially surprising.

“Nobody had it on their bingo card because it doesn’t make any sense,” Petrilli said.

More recently, the administration has taken small steps toward rebuilding IES. McMahon also has promised that the administration of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, will continue as normal. Results from the test, often known as the nation’s report card, have helped drive many education reforms, including ones like school choice that are championed by conservatives.

But many advocates and policymakers fear that the research cuts will mean they have less information about student learning going forward.

“My gut is that it is a lot harder to fix inequalities if you can’t see them, and that is the point,” said Allison Socol, vice president of P-12 policy, practice, and research at Ed Trust, an advocacy group.

The apparent chaos of the Trump administration’s first months was “both highly disruptive and totally necessary,” said Derrell Bradford, president of the education advocacy group 50CAN. The “move fast and break things” ethos of DOGE finally overcame a bureaucracy that has defeated past efforts at reform, he said.

Some advocates hope a more coherent agenda will emerge with the confirmation of former Tennessee state education chief Penny Schwinn as deputy secretary and North Dakota Superintendent of Public Instruction Kirsten Baesler to lead K-12 education. Both would serve under McMahon, who has said that literacy, school choice, and local control will be top priorities.

The barrage of executive orders has made it hard for McMahon to develop her own agenda, Bob Eitel, founder of the Defense of Freedom Institute and senior counsel in the Education Department in the first Trump administration, said on the AEI panel where Neily spoke.

“If you let Linda do it, you will see much more productive action than you have seen in the last few months,” Eitel said.

Enhanced local power over schools: blessing or curse?

Not everyone is looking to Washington for a plan of action. Bradford said there’s no going back to the world of No Child Left Behind or Race to the Top in which presidents seek to use federal leverage to get schools to do better.

“It’s difficult for people to internalize that the federal role has been shrinking for years,” he said. “The primacy of local control is here to stay. If you are a parent, it is far more important that you know who your superintendent is than that you know who Linda McMahon is.”

Trump’s most lasting impact may not be in forcing blue states to change their practices, but in fueling a broader attack on public education that’s given powerful momentum to states’ expansions of private school vouchers, said Jon Valant, director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution.

“The Texas education system 10 years from now is probably going to look very different from the California education system 10 years from now,” Valant said.

To Socol of Ed Trust, Trump’s second term has shown that critical federal functions like protecting civil rights and disseminating research were taken for granted. If the federal government steps back from those roles, local decisions become paramount, she said.

Some communities “will continue to uphold what’s good and right for kids and advance equity,” she said, and others will take the changes in Washington as “permission to walk away” from their commitments. It’s up to parents and community members to pay attention and help decide which way their districts go, she said.

El-Mekki, of the Center for Black Educator Development, worries that anti-diversity rhetoric may deter Black young people from entering teaching and that in the long run, that will be worse for all students. But this summer, his organization is planning for its largest group of fellows yet. With the exception of two that lost federal grants, his school district partners are holding steady as well.

“There are so many people who are pushing back against this,” he said.

Many district administrators are holding off on hiring, and they’re eliminating positions, including support roles that help classroom teachers. Some are worried their states will end up on the wrong side of administration directives, but they’re also preparing for austere federal budgets and the possibility of a recession.

“I know districts that are panicking and districts that are planning as if everything is going to be the same,” said Genevra Walters, a retired Illinois superintendent who now consults with district leaders. “We can’t do either. We can’t panic, but we have to have contingency plans at every level.”

Planning for contingencies can extend beyond education policy. Trade wars could kick the country into a recession, economists warn, bringing with it a rise in child poverty. Immigration raids are driving scared parents to keep their children home from school.

Some teachers wonder what will be asked of them in the coming years. That hit home for Deborah Schmidt, a high school teacher in St. Louis, Missouri, when her school held a training on what to do if immigration agents came to the school — a first in her 29 years as an educator.

“As a history teacher, you start to wonder if you are now in one of those situations where you ask your students, ‘What would you have done?’” she said.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.