Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Selina Yu Ye has been helping immigrant students learn English for nearly two decades. In recent years, she’s seen her students engage in new ways when she brings AI into the conversation.

When one of her fourth graders was reluctant to speak up in class, Ye introduced her to a chatbot from the company Brisk that the student could interact with in both English and her native language. Ye says that soon the student began confidently leading group discussions — with help from her AI companion.

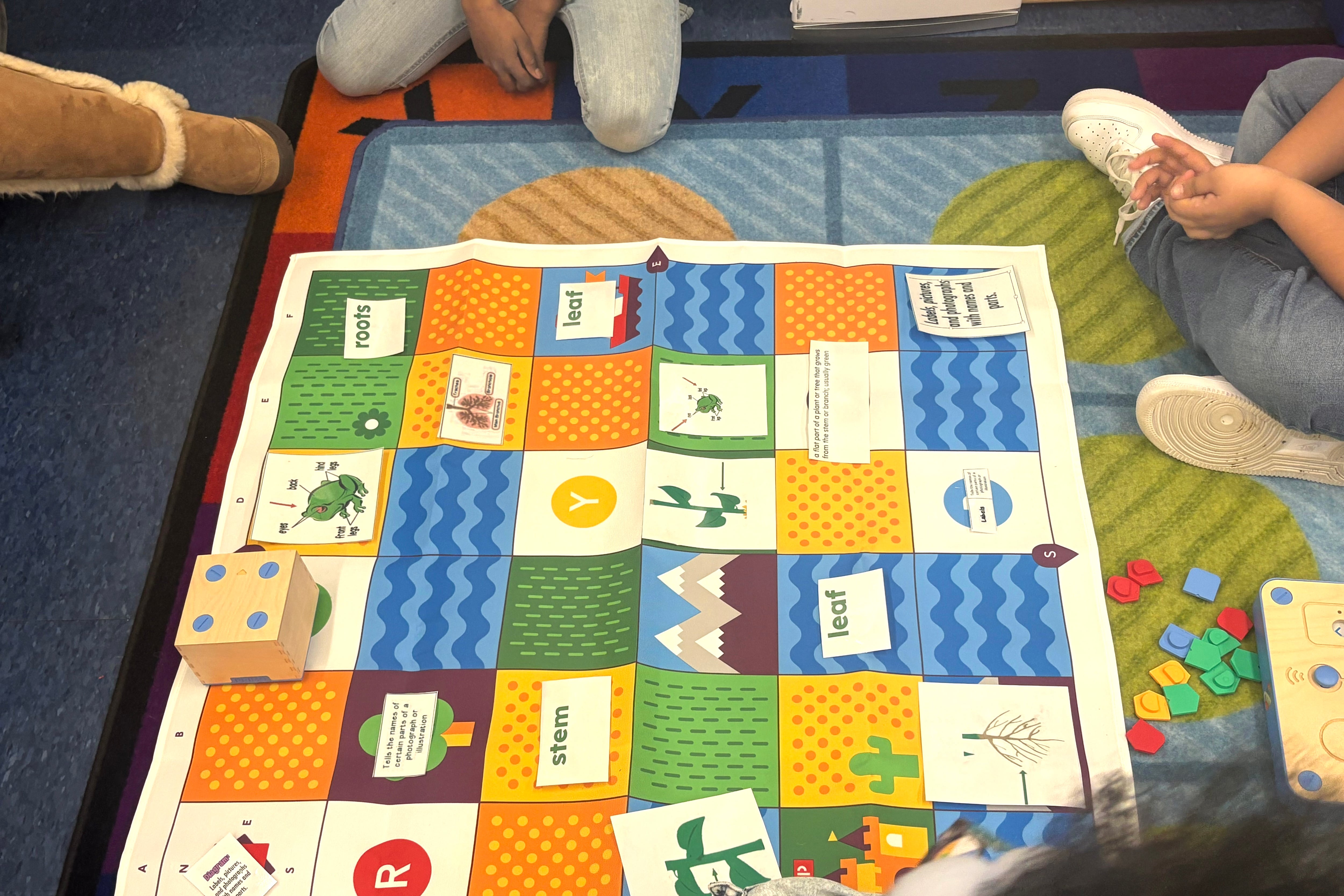

Ye, who’s a literacy coach in New York City public schools, also likes AI-integrated activities involving robots like Cubetto and KaiBot that students can program with voice prompts. Many students shy about speaking aloud will jump at the chance to do so when it involves that kind of exercise.

In such activities, multilingual learners and especially newcomers “feel seen and heard because they notice that the content actually meets them where they are, linguistically and culturally,” said Ye. “I do notice that students participate more in whole class discussions.”

Ye’s work in the classroom is an example of how AI tools have become especially popular for teachers serving English learners and students with individualized learning needs, according to a recent survey by the research corporation RAND. However, some observers worry such tools could exacerbate instructional gaps. Experts also highlight linguistic issues like inaccurate translations, and how AI can even mistake these students’ work as AI-generated. And federal funding cuts could complicate efforts to use the technology ethically and effectively for language acquisition, even as the Trump administration has pushed for schools to rely on AI.

Federal data from 2021 indicated the share of public school students who were English learners was on the rise.

Student-facing AI tools can provide a space for students learning English to get more practice reading aloud with one-on-one feedback.

For example, Amira is what the company behind it calls “an AI-powered reading assistant”. The tool offers feedback in both English and Spanish and recognizes various dialects within both languages. Ye says these AI speech to text tools can provide students the opportunity to practice their oral language skills and hear model pronunciations so that they’re more confident speaking in class.

“It’s a fancy technology, but it’s a very simple premise,” said Joe Siedlecki, Amira’s chief impact officer. “It’s just impossible the way schools are staffed to do one-on-one work with every kid you know for 30 to 40 minutes a week which is generally what kids need”.

Staffing isn’t the only issue that might lead schools to turn to AI to help English learners.

About half of general education teachers report feeling not at all or only somewhat prepared to serve students learning English, RAND’s survey found.

Moreover, addressing the needs of English learners ranked low on principals’ priorities in selecting professional development and instructional materials, even at schools where they make up a large proportion of the student body. Ashley Woo, a researcher at RAND, said that AI can help fill those gaps for teachers by modifying classroom materials to meet student’s language proficiency and reading levels.

AI tools can also help analyze student’s assessment data to identify gaps in their instruction, said Margarita Machado-Casas, president of the National Association of Bilingual Education.

But all that doesn’t necessarily mean AI-driven differentiated instruction is in the best interest of students, said Robbie Torney, senior director of AI programs at Common Sense Media.

English language learners are more likely to miss out on grade-appropriate assignments, and they’re less likely to have teachers with high expectations and receive strong instruction. With many teachers already underprepared to deal with English learners, Torney worries that relying on AI to make reading passages easier for these students could amplify inequitable access to grade-level materials.

AI-powered translation can also be inaccurate or misrepresent the original sentiment of a text, Machado-Casas warned; a quarter of teachers using AI say it helps with translation, RAND found. Sometimes translations can also simply produce lower-quality materials; when Amira first began Spanish reading instruction they used stories translated from English. After instructors and students reported their disengagement, the company switched from translated material to stories written by native Spanish speakers.

Moreover, English learners may be unintentionally hurt by teachers’ efforts to root out AI-generated writing material. A recent study at Stanford University found that AI detectors tend to falsely identify essays by non-native English students as AI-generated, despite being “near-perfect” with their native English counterparts.

“We have to think about some of the systemic influences associated with the application of AI,” said Torney. “It’s about using the technology well to teach kids. It’s not about just using the technology to personalize for the sake of personalizing.”

Cuts complicate AI support for English learners

The Trump administration has pushed for greater AI integration in schools. But cuts at the U.S. Department of Education, including to education research, could make it a lot harder for schools to identify ethical and effective ways to use the technology, especially when it comes to serving traditionally overlooked student populations.

U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon has announced her intention to prioritize grants advancing AI in education. However, her department’s guidelines for the responsible integration of artificial intelligence do not directly address issues like bias in AI tools, or consider the needs of English learners.

Earlier this year, the Trump administration fired nearly every staffer in the department’s Office of English Language Acquisition. In addition to overseeing funding grants for programs serving English learners, the office maintains the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, a hub for data, research, and best practices.

All that could mean schools won’t have federal guidance or research to help inform their use of AI in supporting students learning English.

AI technology “is moving so quickly that the more we wait and the more we have these conversations without training, I think we run the risk of [AI] being misused,” Machado-Casas said.

Funding cuts to research could also threaten the development of innovative technologies for English language acquisition.

Mark Warschauer, an education professor at the University of California Irvine, is developing Rosita, an AI avatar that helps bilingual families read together by facilitating comprehension questions about books in Spanish and English.

In late April, however, the National Science Foundation informed Warschauer that his grant would be cancelled. A little over a month later, the grant for his lab was reinstated, but now, the pilot of Rosita on PBS platforms has been delayed after Congress ended federal support to PBS for the next two years.

“Innovative technologies have this dual potential to either amplify inequality or help mitigate it,” said Warschauer. “We have to be intentional about how we develop it, use it, and we have to study what works and doesn’t work.”

Norah Rami is a Dow Jones business reporting intern on Chalkbeat’s national desk. Reach Norah at nrami@chalkbeat.org.