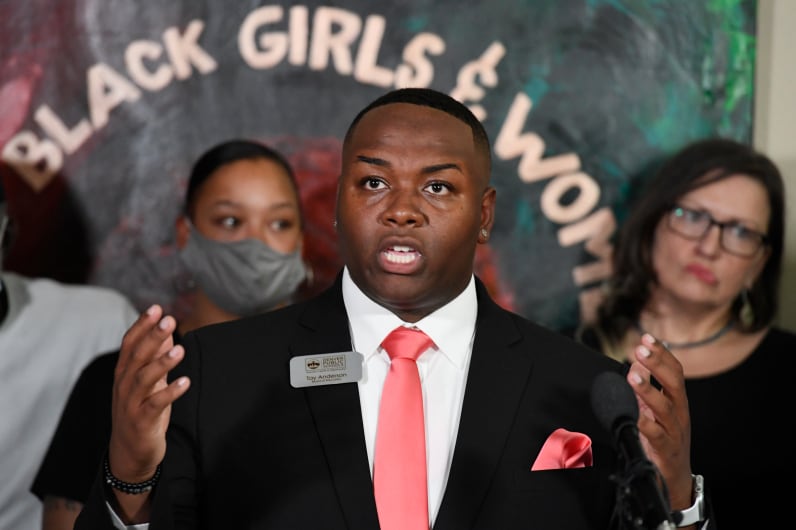

In a long-awaited report, a third-party investigator found that the most serious sexual misconduct allegations against Denver school board member Tay Anderson were not substantiated, but found enough for the board to consider censuring him.

Denver-based Investigations Law Group concluded as unsubstantiated a claim that Anderson had sexually assaulted an unnamed woman, according to the firm’s 96-page report. The woman’s allegation was made public by the civil rights organization Black Lives Matter 5280 in March.

However, the firm substantiated most allegations that Anderson, 23, had made “unwelcome sexual comments and advances” and “engaged in unwelcome sexual contact” toward members of a youth anti-gun violence group called Never Again Colorado, of which he was president in 2018.

The behavior was not connected to Denver Public Schools; the report notes that it took place off district property with non-Denver students. Anderson was not a district employee nor a school board member at the time. He was elected more than a year later, in November 2019.

But the firm substantiated that Anderson had “flirtatious social media contact” with a 16-year-old Denver Public Schools student while he was a board member. It also substantiated that he made two social media posts that were coercive and intimidating toward witnesses during the investigation, which the board commissioned in April.

Not substantiated were claims by a Denver woman in May that Anderson committed sexual assault or misconduct against 62 Denver Public Schools students. The firm also did not find that Anderson committed misconduct while he was employed in a support role at Denver’s North High School or Manual High School, his alma mater, before he was elected.

Investigations Law Group used a “preponderance of evidence” standard, which it explained in the report means that an allegation is substantiated if it is more likely than not to be true. Two invoices show the firm has billed Denver Public Schools at least $105,449 for its work.

A possible censure

The school board said in a statement Wednesday that it would consider a censure against Anderson on Friday and that it would have no further comment until then. Board members cannot remove a fellow member, given that the board is elected by voters. But the board can censure or reprimand a fellow member or remove that member from board committees.

“The most grievous accusations were not substantiated and the board is grateful for that,” the board’s statement says. “However, the report reveals behavior unbecoming of a board member.

“As elected officials, we must hold ourselves and each other to the highest standards in carrying out the best interests of the district. Director Anderson’s behavior does not meet those standards.”

Anderson is serving a four-year term on the school board. He is a Denver Public Schools graduate and has long been an activist, leading protests against racism and police brutality, which has made him a target of conservatives.

Statement from Anderson

In a tweet that featured the words “let’s get back to work!” Anderson issued a statement emphasizing his cooperation with the investigation and expressing hope for community healing.

“I believe the most important message that can be conveyed at this time is that the finding of unsubstantiated claims against me is in no way a victory over survivors, but rather an opportunity to reconsider how we view and create not only restorative, but also transformative justice, for survivors, falsely accused, and correctly convicted,” the statement said.

Anderson said he planned to “address the report in its entirety” at a press conference after he’d had a chance to review the document with his attorney.

The other six board members received the results of the investigation Monday. Anderson got them Tuesday, a day before they were publicly released. Parts of the report are heavily redacted, including a section about student-related allegations.

Portions of a section about Never Again Colorado were redacted “because Director Anderson asserts that they violate his privacy interests,” according to the board’s statement. The board said it believes the report should be “as transparent as possible” and plans to ask a judge to determine whether it’s appropriate to release the redacted information.

Details of the findings

The report begins with an acknowledgement of the complicated context of the investigation, given “the history of racism in relation to allegations of sexual assault, the historical mistreatment of sexual assault survivors, and the volatile landscape of social media.”

“These three constructs combined to create a difficult environment for witnesses to feel safe in coming forward, and for Director Anderson to feel that he has obtained a fair process,” it says.

“Our team is trained in working in this challenging environment, and our process provided for checks and balances to ensure fair treatment of all parties and fair analysis of all evidence.”

Investigations Law Group interviewed 63 people for the investigation, the report says. It did not interview the alleged victim of the sexual assault allegation, despite repeated attempts. The report says the alleged victim declined to participate in the investigation.

Instead, the alleged incident was described to investigators by an intermediary — the same woman who made the claim about the 62 alleged victims. The woman told investigators that the sexual assault happened in May 2017 when Anderson and the alleged victim worked at a now-closed Krispy Kreme donut shop on Denver’s 16th Street Mall.

But investigators said the credibility of the woman’s secondhand account was “not strong.” They cited inconsistencies in her story, among other issues. Investigators were also not able to confirm that Anderson worked at Krispy Kreme in May 2017. Records from the company that did payroll for the store show he stopped working there a month prior, the report says.

Investigators did interview 11 people associated with the now-defunct Never Again Colorado group. Evidence showed Anderson made unwanted sexual comments and advances toward women in the group, most of which Anderson admitted, the report says.

“Nearly all of this behavior was not welcomed by the recipients,” the report says. “The dynamic was heavily influenced by the power disparity between Director Anderson, as a well-known and influential activist, and these high schoolers, many of whom looked up to him.”

Anderson was 19 when he got involved with the group, but then turned 20. The other participants in the situation were 17 and 18 years old, the report says.

The report describes a “party atmosphere” within the organization, and notes that Anderson participated in it. But it says he did not solely create the atmosphere and later stepped down as the group’s president and apologized.

More details

Investigators said they found two instances of Anderson communicating with high school girls while he was a candidate and board member that were “objectively flirtatious.” The most recent exchange happened last year between Anderson and a girl who was 16 at the time.

In messages between them, Anderson told the girl they should be friends, asked her if she lived with family or had her own place, asked her what she did for work and if she knew how to make pizza. When she said yes, he said, “You’ll have to teach me I know that’s basic but still.”

Anderson said he didn’t know the girl’s age when they started messaging. When he found out she was a teenager, he stopped, he said. He called the messages “a mistake,” the report says.

Anderson also made two social media posts during the investigation “that could reasonably have been interpreted as coercive or intimidating against witnesses,” the report says.

One post involved a meme of Bugs Bunny with a shotgun to his chest and the words “do it bitch.” Another post was a statement Anderson made on Facebook warning people who disparaged him not to speak to him again.

Witnesses could have seen the meme as threatening, and the second post as retaliatory, the report says. But investigators noted that it’s unlikely Anderson’s posts had a chilling effect on their work. “Most of the behaviors identified by witnesses as retaliatory fall into the realm of heated social media rhetoric,” the report says.