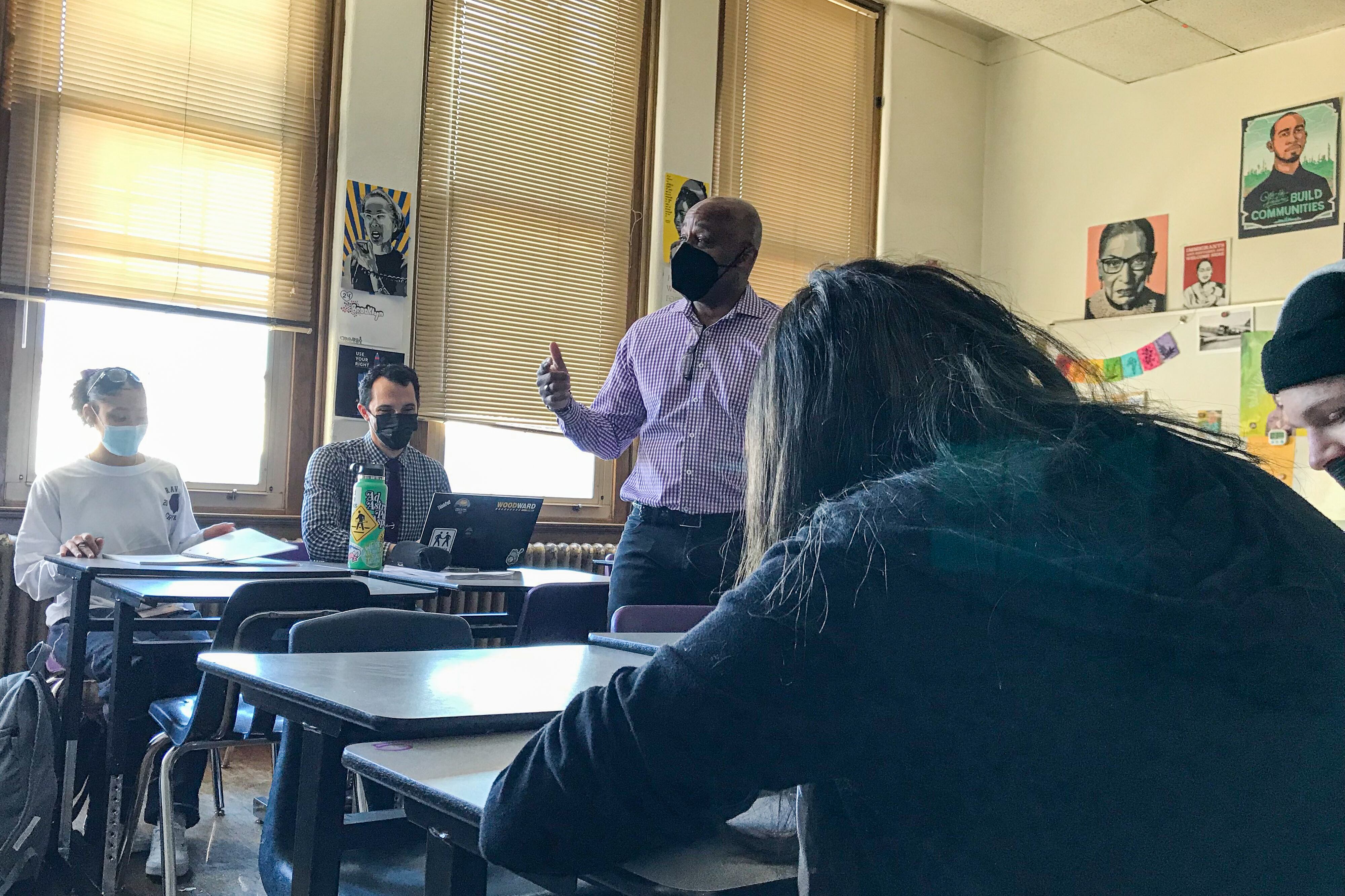

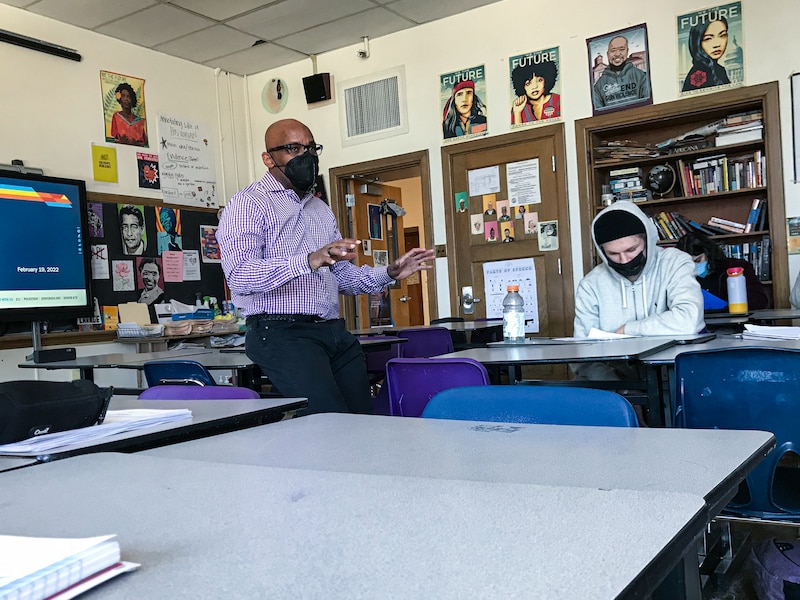

Wearing a checked dress shirt in South High’s colors of purple and white, Denver Mayor Michael Hancock gave the juniors and seniors in Friday’s fourth-period Advanced Placement Government class a one-question pop quiz.

“True or false,” he said. “The foundational value of our democracy is voting.”

There was a pause. Not an extraordinarily long pause, but not a short one either. It was the kind of pause any substitute teacher might get, before a girl in the back quietly answered that voting may have been central to the founding of our democracy, but not everyone was allowed to do it.

That history, and how efforts to block some voters from exercising their rights persist today, were central to a lesson Hancock taught to three classes Friday. His guest appearance at South had dual purposes: to talk to students about a topic he’s passionate about and to call attention to Denver Public Schools’ pandemic-era substitute teacher shortage.

“It underscores the need we have to get professionals who have time to come into the schools and help out,” Hancock said of the reason for his visit.

Staff shortages have been a defining and difficult element of the COVID-19 pandemic at schools across the country. Teachers exposed to COVID, sick with COVID, or caring for sick family members have been quarantined at home, sometimes for weeks in a row. Schools are struggling to find substitutes who will risk their health for relatively low pay. Several Colorado districts have asked parents to help. New Mexico called on its National Guard.

The Denver district has tried to make subbing more enticing by increasing the daily pay to $200 for those with a teaching license and $160 for those without one, said spokesperson Scott Pribble. The district also started reimbursing for state licensing costs and is offering a $400 bonus for subs who work at least 10 days per month, he said.

During the recent omicron wave, Superintendent Alex Marrero reinstituted a rule that employees who work in the district’s central office must substitute in a school one day per week. Even with that support, and with the nearly 600 new substitute teachers Denver has hired since the fall, the district can only fill about 63% of teacher absences each day, Pribble said. That’s down from 83% in the 2019-20 school year, which was interrupted by COVID.

Dozens of Denver schools had to temporarily switch to virtual learning last month due to staff shortages. The need for more subs came up repeatedly in an anonymous survey of 601 school staff members conducted by Denver’s district accountability committee in December.

“We don’t have enough coverage when teachers are sick,” one teacher wrote.

Though Hancock was in command of the fourth-period class at South, he wasn’t really subbing. The actual teacher was sitting at a school desk next to his students (as well as a member of the mayor’s security detail, his deputy communications director, and a reporter).

But Hancock taught an hour-plus lesson that included PowerPoint slides, a video, and an opportunity for the students to write a one-minute speech to Congress about whether to pass two pending bills related to voter rights. The mayor was at ease in the classroom, leaning against a desk as he cold-called on students whose names he’d quickly memorized.

“Knowing there are efforts to restrict and suppress voting, how does that make you feel?” Hancock asked the students after telling them about an order by the Texas governor limiting the number of ballot drop-off locations in each county to one.

“It’s not what America is advertised to be,” a student named Jack said.

“What is America advertised to be?” Hancock prodded.

“Free,” Jack said. “To all people.”