David Delaplane pondered a crucial question in his tiny Glenwood Springs cabin.

How could the local chamber of commerce that he managed improve education in the area? His answer was to start a college — an ambitious goal for a chamber that hadn’t recorded any education work.

Delaplane said he contacted the chamber’s education committee and “they said, ‘Well, yeah, let’s go for it.’”

Today, Delaplane’s idea lives on as Colorado Mountain College and has shaped the lives of over 25,000 graduates since the school was founded in 1965.

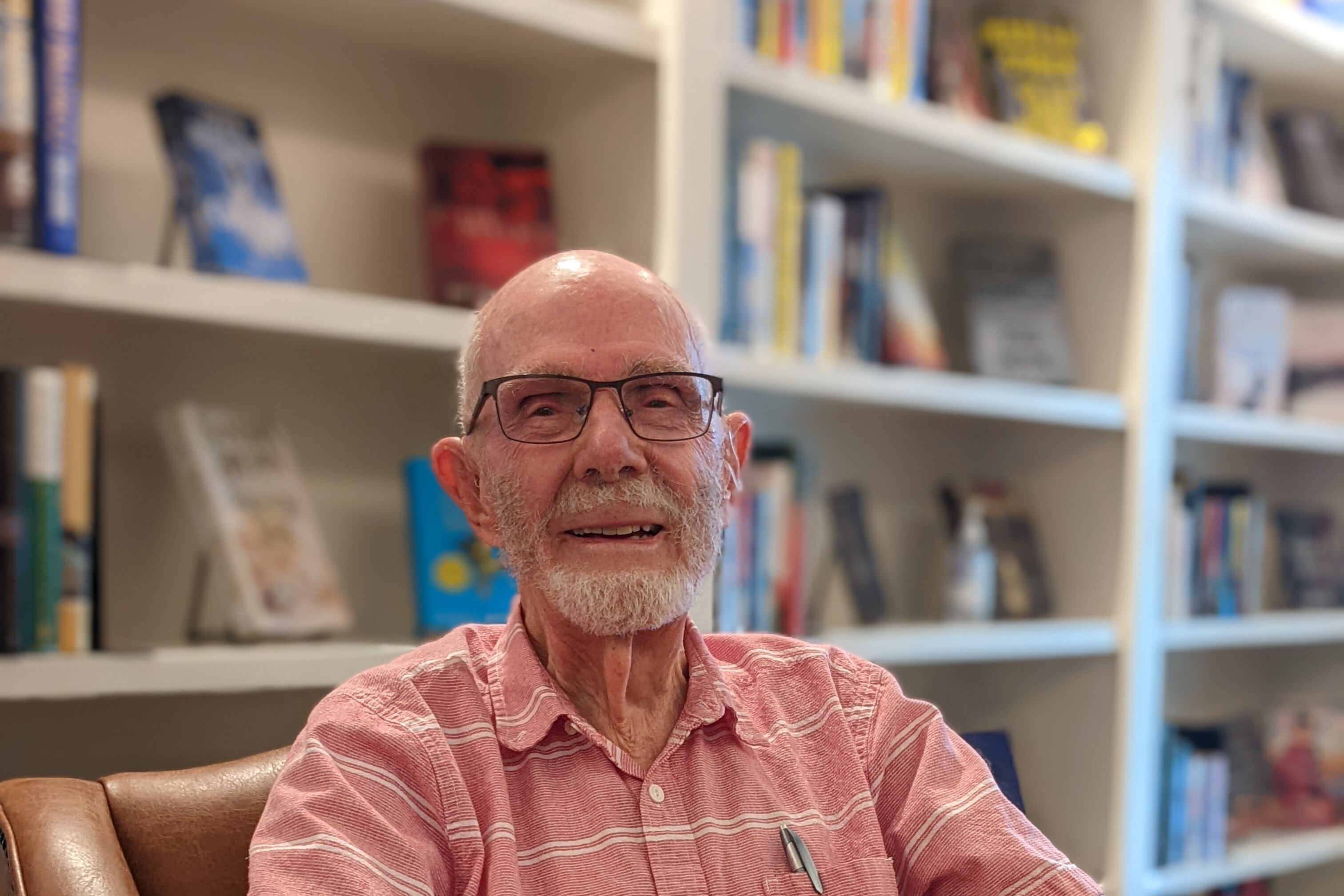

Delaplane, 94, never imagined his creation would expand across the Western Slope and eventually offer bachelor’s degrees. He sees it as one of the great college success stories, growing from two campuses to 11, covering over 12,000 square miles.

Delaplane recently reflected on getting students in rural mountain areas access to college. Here’s what he had to say.

Why did Delaplane see the need for a college?

While managing the chamber, Delaplane also served as a pastor. His path to become a pastor included education at three colleges. Higher education has been an issue he cared about deeply.

At the time, Glenwood Springs and other mountain towns weren’t the resort towns they are today. There was no ski industry, and Interstate 70 wasn’t finished. The gateway to mountain towns ran through Loveland Pass, a long journey to Denver and the Front Range.

Residents had few nearby, convenient college options.

Delaplane wanted to make it easier for students, especially the kids of ranchers and farmers, to get an education.

“I wanted to try to at least get something started where young people could at a reasonable cost go to college closer,” he said.

How did Colorado Mountain College become a school?

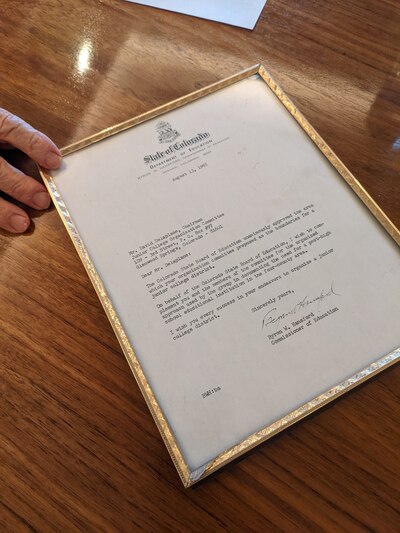

To start a school, Delaplane and the chamber needed to petition the Colorado Department of Education and State Board of Education for approval. They received unanimous support. Delaplane still has the letter from Aug. 13, 1965, allowing the chamber to go ahead with its idea.

Delaplane and the committee toured the five surrounding counties to ask voters to tax themselves to create a school and use the money to fund its operations. Four of the five counties voted for the measure, ensuring the school’s foundation. Delaplane and local leaders didn’t have a road map for establishing a college. The president of what is now Colorado Mesa University offered advice: First, he said, hire a president.

How has the school changed?

Delaplane and the board landed a president from Michigan. But the succeeding years of the school were marked by tragedy. The school’s first and second school presidents died in plane crashes.

Early college courses included commercial art, English, data processing, welding, and agriculture. In 1971, as ski areas grew and multiplied, the Leadville campus began a one-year certificate in ski area operations. A school spokeswoman said it reportedly was the only program of its kind in the country.

What do local leaders say about the impact of the college?

The school now offers two- and four-year degrees, including jobs that connect students with the health care and the ski industries. The school also houses students, in an area where finding affordable housing is difficult.

Earlier this year, state lawmakers pointed out Colorado Mountain College as an example for its work tailoring programs to meet the needs of local industries. The school develops many of its programs in partnership with business leaders.

That’s always been the relationship the school has with the community, said Angie Anderson, Glenwood Springs Chamber Resort Association CEO and president.

The local tax carries on and is unusual among higher education institutions that receive the majority of their funds from the state. Instead, Colorado Mountain College receives the majority of its funding from its local tax base.

Anderson believes that the use of local dollars makes Colorado Mountain College leaders more responsive to the community because the school must continually show it’s a worthwhile investment. And the special tax is used by the school to keep tuition low for students who live in the area.

“They work really, really hard to ensure that they’re serving the communities that are basically funding them,” Anderson said.

How does Delaplane see the impact on students?

Delaplane often wears a Colorado Mountain College hat, which he said helps strike up conversation with former students. Most recently, he found out a nurse at his doctor’s office graduated from the college, a training program he never originally envisioned in his cabin.

“It’s just wonderful to know that you’re meeting people who tell me that they got their start at Colorado Mountain College,” he said.

Jason Gonzales is a reporter covering higher education and the Colorado legislature. Chalkbeat Colorado partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage. Contact Jason at jgonzales@chalkbeat.org.