Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

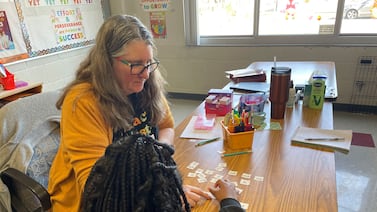

Teachers, child care providers, and other people who work with children will soon be subject to a new state law governing how and when suspected child abuse or neglect should be reported.

The law, which takes effect Sept. 1, includes several changes recommended by a state task force that spent two years considering reforms that clarify the responsibilities of mandatory reporters — people who work with kids and are legally required to report suspected abuse or neglect. The new law includes a provision aimed at reducing the disproportionate number of low-income families and families of color who are reported for suspected abuse or neglect.

Some of the task force’s recommendations didn’t make it into the new law because they would have cost more money than state lawmakers wanted to give in a tough budget year. They include a recommendation to require standardized recurring training for mandatory reporters.

Below are answers to common questions about the new law.

If I suspect child abuse or neglect at work, how soon do I have to report it?

The new law requires that mandated reporters make a report within 24 hours. The old law required a report “immediately” but did not define the term, which led some mandated reporters to wait 48 or 72 hours before reporting, according to members of the task force.

If I see signs that a child in my classroom is being abused or neglected, can I let my supervisor make the report instead of doing it myself?

No, you must make the report. The new law prohibits employees from delegating their duty to report to a colleague or supervisor who doesn’t have firsthand knowledge of the suspected abuse or neglect.

In the past, employers such as schools or hospitals sometimes had rules that required employees who suspected abuse to report it to their supervisors instead of going directly to authorities. The idea was that the supervisors would make the report to authorities, but in some cases, they never did. The new law attempts to close that loophole.

Schools and other employers can still require educators to report suspected abuse or neglect to supervisors or go through other internal procedures, but those educators must report to authorities as well.

If multiple mandated reporters at my job see signs of abuse or neglect at the same time, who should report it?

If you are a mandatory reporter, you should always report suspected abuse or neglect. However, if a colleague has reported the same instance you are calling about, you will not be required to make a full duplicate report. Instead, you will receive a referral identification number that fulfills your duty to report.

Does the new law take race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or disability status into account?

The law prohibits reports due to these factors. Experts say this change came about because families of color and low-income families are disproportionately funneled into the child welfare system because manifestations of poverty, racial identity, ethnicity, or disability are sometimes conflated with abuse or neglect.

For example, if a child wears the same clothes four days in a row or tells the teacher they’ve been sleeping on the couch at their aunt’s house, it might not be neglect, but an outgrowth of financial problems, said Jessica Dotter, sexual assault resource prosecutor at the Colorado District Attorneys’ Council and a member of the state task force.

She said teachers should pause to ask questions like, “Is this neglect, or is this poverty? Is this neglect, or is this a kid with two parents who are disabled?”

As a teacher, I’m a mandated reporter. Does that mean I have to report suspected child abuse or neglect that I see outside my job?

No. The old law wasn’t clear on this point, but a 2019 Colorado Court of Appeals decision held that mandatory reporters are obligated to report suspected abuse or neglect even if it happened outside of work. The law change specifies that mandated reporters are not required to do this.

While mandated reporters don‘t have to report outside-of-work instances of suspected abuse or neglect — for example, something they saw at a kid’s soccer game — there’s nothing preventing them from reporting if they choose.

What happens to mandatory reporters if they fail to report suspected abuse or neglect?

If mandated reporters knowingly fail to report, they can be charged with a Class 2 misdemeanor, which carries a maximum of 120 days in jail and a fine of up to $740. But the likelihood of going to jail for violating the law is low, according to an analysis by Dotter.

She found there were 70 failure-to-report cases from 2010 to 2020, and 41 of them were dismissed. In only 19 cases, mandated reporters either pleaded guilty or were found guilty. They were all given probation or another sentencing option that did not include jail time.

“Even though there’s a possibility of jail,” said Dotter, “in 10 years, there was not one case where jail was the outcome.”

Am I a mandatory reporter?

There are more than 40 categories of mandatory reporters under Colorado law. They include public and private school employees, child care employees, nurses, psychologists, social workers, mental health professionals, and coaches. For a full list, check out the FAQ from the Colorado Department of Human Services.

Where can I find information or training on the new law?

The Colorado Department of Human Services offers free online training in English and Spanish for mandatory reporters. A new version of the two-hour training that includes information on the recent law change will be available starting Sept. 1.

For general information about child abuse reporting rules and resources, check the department’s CO4KIDS webpage.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.