Gov. Andrew Cuomo laid out strict benchmarks New York City must meet before reopening schools this fall and will require buildings to shut down if there is a resurgence of the coronavirus in the area.

New York school districts will be allowed to reopen if the surrounding region has reached the fourth and final phase of reopening and the daily infection rate is below 5%, based on the proportion of tests coming back positive and based on a 14-day average, Cuomo said Monday. State officials will determine if New York City, which counts as its own region, has met that threshold in the first week of August.

But if the city’s infection rate surges past 9% later in August or after the school year starts (based on a seven-day average), schools will be forced to shut down again. Fewer than 2% of coronavirus tests in New York City have come back positive in recent weeks, state data show, though the city has not yet reached phase four of reopening.

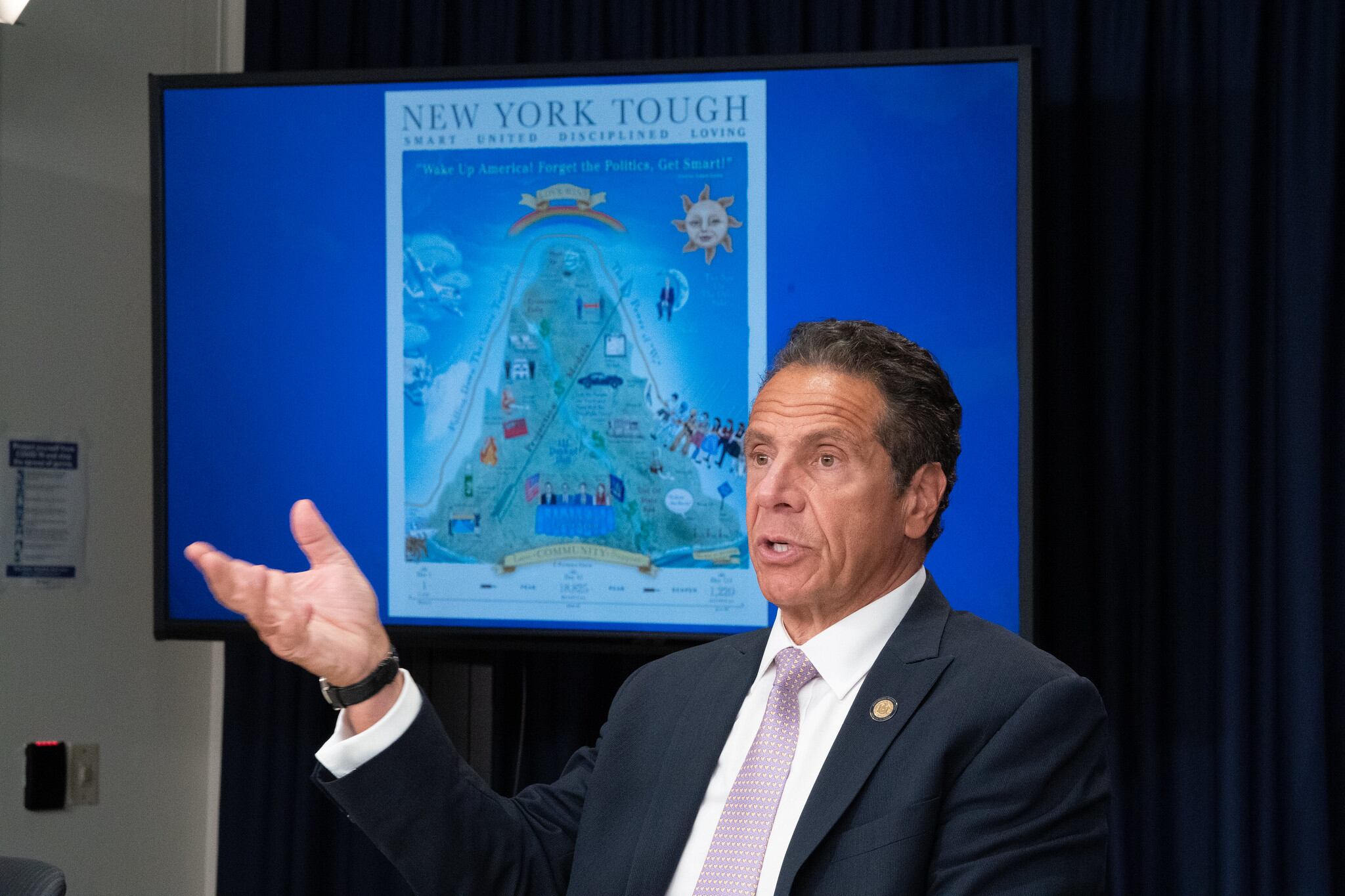

“We’re not going to use our children as guinea pigs,” Cuomo said during a press conference, repeatedly criticizing President Donald Trump’s stance that school buildings should reopen across the board. “You can follow the number — that’s what’s nice about this. There’s no politics, there’s no personal opinion, there’s no vaguery.”

New York City schools, which announced a reopening plan last week, has not yet said how it would screen students or how it would address positive cases of the coronavirus at its school buildings. Last week, city officials said they don’t believe schools would have to close down — as they did before buildings closed in March — if a positive case pops up.

All school districts across the state are required to submit their reopening plans by July 31, which education officials must simultaneously make public. A spokesperson for the governor, Jason Conwall, said the state does not anticipate providing districts with more funding to aid their reopening plans, as the coronavirus has blown a hole in the state’s budget. Cuomo has previously warned that education cuts could be in the offing without additional federal stimulus money.

Also on Monday, the state education department gave a preliminary look at what reopening plans should address in New York’s 732 school districts. While the full guidance won’t be released until Wednesday, the state spelled out some specific requirements, including masks for students and staff, screening students for virus symptoms, and regular disinfection of buses. State guidance will address various parts of daily school life, including school schedules, transportation, instruction, and social-emotional support.

“This will continue to be a work in progress,” said Vice Chancellor T. Andrew Brown. “We have no doubt that additional issues and problems will arise and the field will require guidance, and we’ll continue to provide that guidance.”

The state Department of Health also released more health-related rules for schools Monday. That will include checking everyone’s temperature every day and sending students or staff home if their temperatures exceed 100 degrees. Schools must also report any positive cases at a school to state health officials, and log every time they clean and disinfect buildings.

New York City last week said that students would learn through a combination of in-person and remote learning. Schedules will vary based on the number of students and space within each school, allowing for social distancing. That plan falls in line with the new state guidance, which asks districts to consider various learning models.

Also conforming with state guidance is New York City’s plan to require students and staffers to wear masks. Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has said students won’t be disciplined for not wearing them, rather, they will be “encouraged” to pull them on — raising concerns among some educators and parents who are wary of returning to buildings.

Pico Kassell, a public pre-K teacher at Roosevelt Island Day Nursery, worries about the various challenges masks can pose for the city’s youngest learners, such as conveying their needs to a teacher as they’re still learning word pronunciations.

“I was talking to other teachers and we were wondering, well, how many masks would they have to have because we’re sure they’re gonna sneeze in them, and do they have to change their mask after snack?” she said.

As state guidance will require, New York City schools will have an isolation room for any student who feels ill during the school day. The city also plans to disinfect school buildings every night.

But the state requirements also underscore many questions that city officials haven’t yet addressed for the fall.

Districts will be required to train staff on how to screen students for illness. School systems must also provide transportation for all students who need it. The city has not yet said how it will handle either of those issues. On Friday, Mayor Bill de Blasio said the city will announce “shortly” how it would address entry into school buildings.

The city is “currently assessing ways to provide safe transportation options this fall,” said Miranda Barbot, a spokesperson for the city’s education department. Officials are considering a plan that would provide busing only to special needs students whose education plans require busing, the New York Post reported over the weekend.

On instruction, state education officials said districts must provide all students with “clear opportunities for equitable instruction” with curriculum grounded in state standards. Teachers must interact with students daily in a “substantive way.” There must also be “clear communication” between schools and families, state officials said. Officials did not elaborate on how districts should tackle any of these points, but more detailed information could come when the full guidance is released.

No matter the learning model, schools will be required to provide physical education classes in some form, officials said. Educators should plan a “menu” of activities for students to complete, even if that means students completing work on their own time.

Districts should provide devices and technology support for students, families and teachers. They should also offer teachers professional development focused on “best practices” for remote instruction, state officials said.

Schools should also be required to spell out how they’ll provide high-quality instruction to students who are learning at home, according to Ian Rosenblum, executive director of Education Trust-New York, an advocacy and civil rights organization that joined several groups in calling for specific instructional policies as districts reopen. That instruction should include culturally relevant and anti-racist curriculum, he said.

“Either we are coming back to school with the widening inequities that have been exacerbated by the pandemic, or we are going to take steps to start addressing those inequities,” Rosenblum said. “So these questions about curriculum and support for students can’t be an afterthought. They need to be right there alongside health and safety issues as we think about a way to reopen in a way that supports all students.”

Social-emotional support should be the highest priority for districts, state officials said. They made clear that districts should offer “multi-tiered systems of support,” but on Monday did not provide specifics about how districts should do that aside from reevaluating their counseling practices.

Several Regents raised concerns about how districts would pay for resources tied to the mandated health guidance, such as thermometers for temperature checks or masks, as cities are grappling with the pandemic’s financial aftershock. Officials in New York City, which cut the education department’s budget by $773 million this fiscal year, have not yet disclosed how much personal protective equipment will cost. The education department said costs won’t be clear until closer to the start of the school year.

“It is clear that in a number of places, resources are necessary and are not givens that can be taken for granted,” said Regent Luis Reyes.

The state education department has raised those concerns with the governor’s office, state officials said.

“It’s a difficult fiscal environment right now, so I envision this is going to be a challenge, but certainly it’s not going to stop us from advocating for the needs of the school districts in meeting those expectations,” said Phyllis Morris, the department’s chief financial officer.