Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

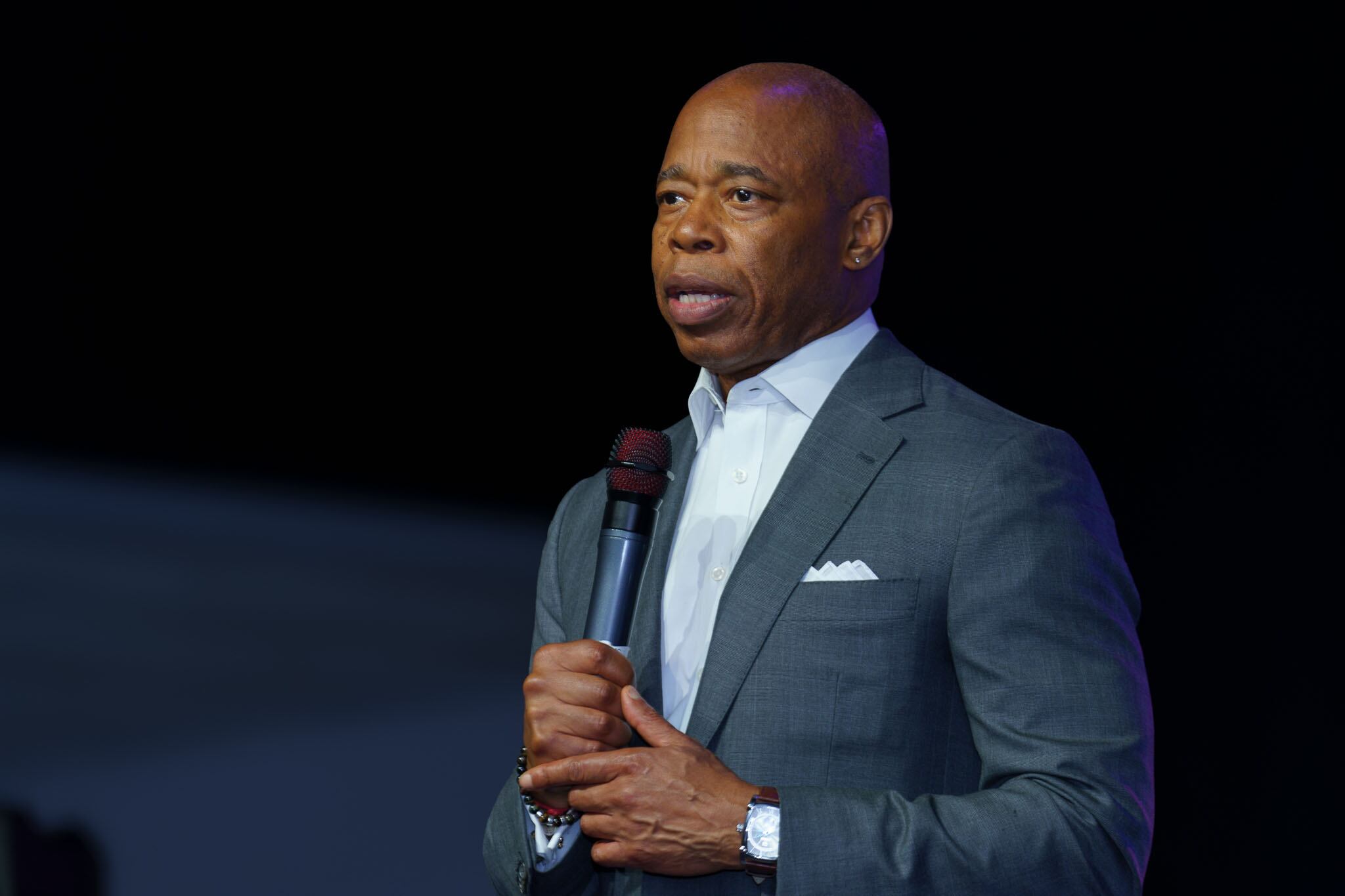

New York City schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos told elected and union officials Friday that she never received a recent memo from Mayor Eric Adams’ office that appears to give city workers more leeway to let federal immigration agents into public buildings, according to people familiar with the conversations.

The Jan. 13 memo allows city workers to let federal agents into public buildings without a warrant signed from a judge if they feel “reasonably threatened” for their own safety or that of others, according to a copy of the memo obtained by the New York Times. It sparked immediate outrage from elected officials and advocates, who said the language makes it easier for federal agents to gain access to city facilities and undermines sanctuary protections at schools, shelters, and hospitals.

But in a statement posted to social media Friday night, the city’s teachers union said “Chancellor Aviles-Ramos informed us the DOE did not receive the mayor’s new guidance for city agencies on federal agents attempting to enter city property. The DOE’s existing policies remain in effect.”

Aviles-Ramos offered a similar message to elected officials, though some wanted to see a clearer commitment in writing, according to a source familiar with the conversations.

Education Department spokesperson Nicole Brownstein said in an email that the guidance for public schools “is clear and unchanged — we do not permit non-local law enforcement into schools unless required by law." The official guidance for city schools is posted on the Education Department website, she added.

But when asked to confirm if that means the City Hall memo does not apply to public schools, Education Department officials referred the question to a spokesperson for Adams, who did not immediately respond. The spokesperson also didn’t immediately respond to a question about whether the memo applies to school safety agents, who are employed by the NYPD.

Union officials said the Education Department plans to send out a statement to families, but as of Friday evening, the department had not done so.

The Education Department’s longstanding guidance instructs principals to ask federal agents for any documentation, then call department lawyers to await instructions. The guidance does not give school employees permission to let the agents inside if they feel threatened, though it does instruct them not to try to physically interfere with an officer who ignores their instructions.

City officials reiterated that protocol to school principals in recent months and have held training sessions with principals and other school employees.

News of the Jan. 13 memo, first reported by Hell Gate, provoked a wave of condemnations from elected officials.

“The recent City Hall memo provides unclear and troubling guidance on interactions with federal immigration officials, creating unnecessary fear and confusion for our educators, students, and families,” said Brooklyn City Council Member and Education Committee Chair Rita Joseph in a statement on the social media platform X. “This is simply unacceptable.”

United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew said there have been “no substantiated instances of [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] agents attempting to enter our schools.” But fears have remained high amid President Donald Trump’s efforts to ramp up deportations, sparking rumors of immigration agents at schools, and keeping some kids home.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org