A startling rise in failing grades during the pandemic was one of the most worrying signs that students were struggling.

Now, high schools in particular have a challenge ahead: figuring out how to help those students recover academically without falling off track for graduation.

For many schools, the go-to method is online credit recovery. After students fail algebra or English, students typically take a virtual make-up course at their own pace, often in a room with other students making up courses. It’s a convenient solution for students and schools, and research has shown students do successfully recover academic credits this way.

But it also has big downsides. Students often don’t have access to an adult in the room who teaches the subjects the students are learning. Classes are typically large. And several studies have raised serious questions about whether students actually learn the content this way, finding that it’s not uncommon for a student to guess or Google their way through.

“Doing credit recovery well is the hardest thing that we can do in education,” said Nat Malkus of the American Enterprise Institute, who has studied the spread of credit recovery programs across the country. “We’re gathering in the kids who have the biggest challenges there and then we are often trying to fix those with instruments that don’t have the things that we would think are most likely to help them.”

As school leaders decide who needs credit recovery and how those programs should be run — with more funding than they’d typically have — educators and researchers who’ve studied these programs say this is a big opportunity to make them better.

Here are some steps they can take:

First, think carefully about which students should be offered credit recovery, and for which courses

Carolyn Heinrich, a professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University, is part of a team that’s studied online credit recovery in Milwaukee’s public schools for seven years. Her research found that younger high schoolers are more likely to log in but sit inactive.

It was partly “because of reading levels, but also just because of students’ self-regulation and motivation to work hard in those courses,” Heinrich said.

Now, the district discourages ninth and 10th graders from making up credits online — something other districts may want to consider.

Schools may also consider whether students should make up core classes online at all.

Samantha Viano, an assistant professor of education at George Mason University, found that high school students who took math, English, and biology classes through online credit recovery scored worse on end-of-the-year exams than students who’d made up the credits in-person, suggesting they’d learned less of the material. The results were especially pronounced in biology — raising questions about whether science courses, with their hands-on labs, are especially ill-suited for online credit recovery.

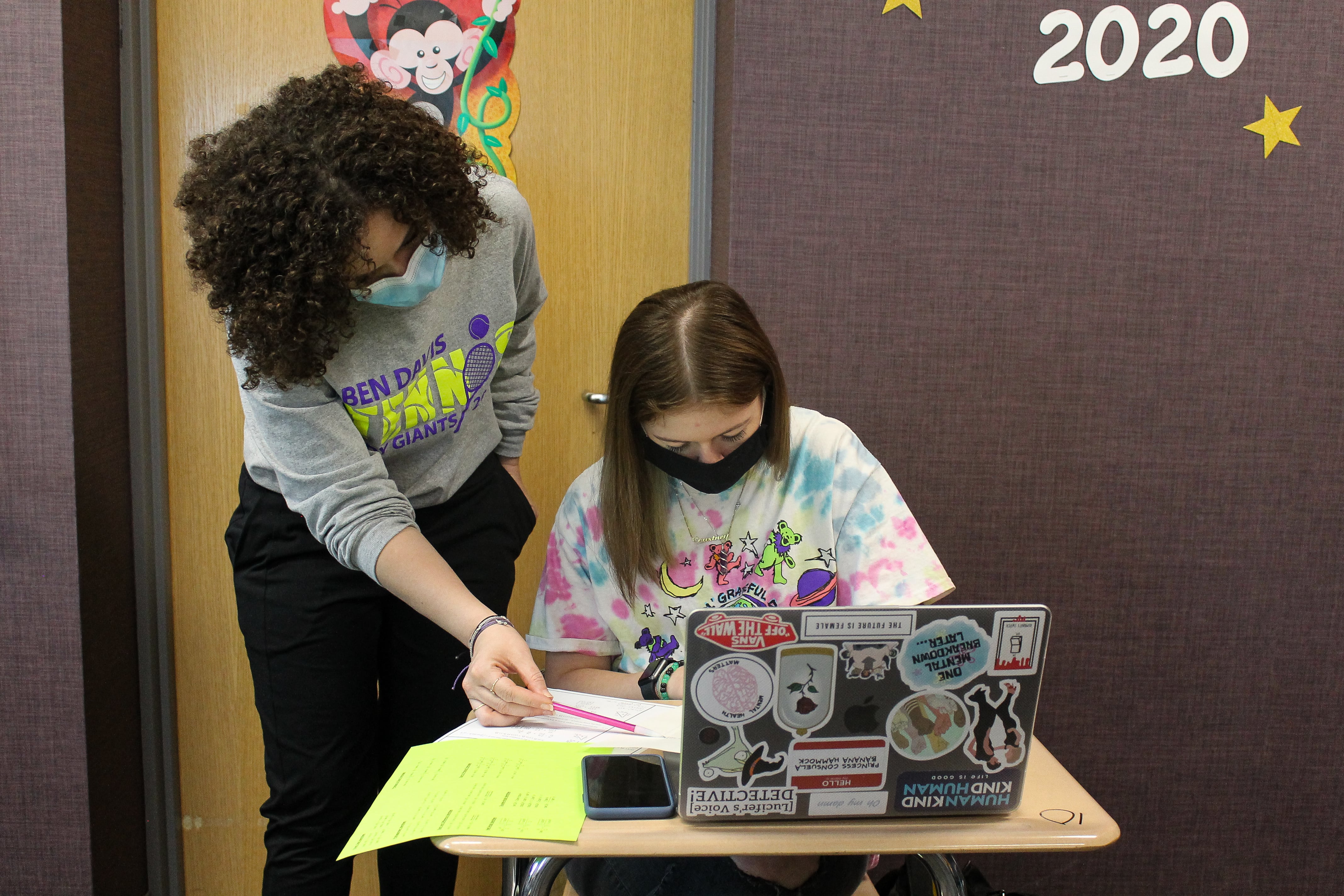

If you go the online route, provide teachers who know the content and can monitor student progress

Many researchers and educators agree: The quality of online credit recovery has a lot to do with how you staff it.

To do it well, Heinrich said, students need support from a teacher and to interact with their peers. Smaller class sizes help, too, because teachers can sit down with students and reteach concepts.

Elaine Allensworth of the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research and her team found that students in an algebra credit recovery program in Chicago tended to be more successful when they took the class in person. But students who took it online were more successful if they had a math teacher working with them.

“Having teachers in the classroom with students definitely increases the likelihood of success, especially teachers with content knowledge in the subjects that students are taking,” Allensworth said.

The next best thing: Any teacher or staff member who takes a hands-on, proactive approach.

“The mentor in the classroom should actually look at: Are the students making progress? Are they getting the different assignments and assessments done?” Allensworth said. “And if not, reach out to the student and say, ‘OK I’m going to help you,’ and it’s not an ‘Oh, come to me if you want help.’”

Find out why the student failed and focus support

At a time when students may be struggling for many different reasons, many educators and researchers agree that it’s especially important to try to figure out why students failed a class.

If they didn’t understand the content, they’ll likely need a teacher to help them through. If slow internet or distractions at home were the issue, coming into the school building could address that. And if a student disengaged from school entirely for a period during the pandemic, online credit recovery may not be appropriate at all, and schools should consider having the student re-take the course in person.

A key question schools should be asking, Viano said, is: “Did they actually have access to instruction before?”

OneGoal, a nonprofit that helps high schoolers stay on track and plan for college, added more one-on-one check-ins with students during the pandemic to help staff understand what was going on in students’ lives. That, in turn, helped them figure out why students might not have been doing well in a class. Schools can do that too, said Melissa Connelly, the CEO of OneGoal, with advisory periods, homerooms, or other blocks of time when students can talk with a caring adult.

“If you’re going to actually have a viable intervention or solution, it has to address the root cause,” she said.

Be proactive to prevent more Fs

When a student fails a class, it can decrease their motivation and confidence, which can make it more likely that they will get additional Fs. It’s why many schools took a more flexible approach to grading during the pandemic — often offering students more chances to make up missed work or adjusting their grading scales.

Researchers say one of the most important things schools can do right now is to put resources into supporting students as soon as they start to struggle or miss class this year. That will prevent students from having to make up even more missed credits later.

“This is going to be an important time coming up,” Allensworth said. Schools should aim to set students up for success and “if a student shows any signs that they’re struggling at all, someone is right there to make sure that they understand why.”