Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Christian Rojas Linares can’t finish his financial aid forms because he’s been blanketed with error messages. The New York City high school senior has even received incorrect emails telling him his application was canceled.

In Philadelphia, Yasmeen Mutan had better luck: Finishing the form only took her an hour. But the federal government has been so slow to process and share her data that, four months later, she still doesn’t know how much she’ll get in financial aid. Without that, she can’t decide where to go to college. And that means she can’t apply for state financial aid either.

“I’m logging in every couple of days, just to make sure I didn’t miss out on anything,” Mutan said. “I just don’t know what to do.”

With college decision deadlines looming, thousands of high school seniors have been stuck in limbo due to the bungled rollout of the new Free Application for Federal Student Aid. The so-called Better FAFSA was supposed to make it simpler for students to receive financial aid. Yet the mistakes have been numerous and serious enough that high school counselors and advocates for college access now fear that promising students from the Class of 2024 will end up not going to college at all.

As of late March, just over a third of high school seniors had successfully submitted the FAFSA, according to data tracked by the National College Attainment Network. In previous years, nearly half of seniors would have done so by now. Students who complete the FAFSA are far more likely to go to college, so the low completion rates raise concerns about the long-term impact on this year’s graduating class.

And the decline tracked by the network is much greater at schools serving a lot of students from low-income backgrounds and students of color.

Closing off routes to financial aid creates “enormous issues,” said CJ Powell, director of advocacy for the National Association for College Admission Counseling, especially for students whose families have fewer resources. These students, often students of color and children of immigrants, are especially reliant on Pell grants and other aid to afford college. And when they delay college, Powell said, they are less likely to go at all.

“That people will walk away is keeping me up at night,” said Bill Wozniak, vice president for communications and student services with INvestED, a nonprofit that promotes postsecondary education in Indiana. “The people who are most vulnerable and they do everything right and it’s not working, I do worry about that.”

Cascade of problems with new FAFSA form

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

Completing the FAFSA is the gateway to grants, scholarships, and subsidized loans that make college affordable for millions of students. But for years, students and parents found the form to be complicated and stressful.

In 2020, Congress passed legislation to simplify the form, with far fewer questions and more family financial information pulled directly from tax returns that the federal government already has. But the transition proved to be far more technically difficult than anticipated and fell to a U.S. Department of Education that was also tasked with overseeing complicated student debt forgiveness programs, according to numerous reports.

The launch of the new form was delayed, and when it finally came online in late December, it was riddled with technical glitches.

Students from mixed status families, in which one or both parents don’t have a Social Security number, faced some of the biggest hurdles. Workarounds that these students have used for years, such as entering all zeros in place of a Social Security number, no longer worked. And for weeks there was no way for these students — most of them U.S. citizens — to add their parents’ financial information.

In March, the education department announced that the problem was fixed. But many students are still encountering problems even attempting to verify their parents’ identities.

That’s the case for several of Danielle Insel’s students at the Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women in Brooklyn. They are “still going back and forth with just getting their parent’s identity recognized so they can finish the parent section of the FAFSA,” said Insel, the school’s director of postsecondary readiness.

“After five, six, eight attempts, they want to give up,” she said. Students are already telling her, sometimes jokingly, and sometimes less so: “I’m not going to college, I’m not going to get financial aid.”

“It’s demoralizing, frustrating, and yes, I can see it having a direct link to a decrease in enrollment. If not enrollment, then definitely matriculation,” she added.

In group chats and on message boards, college advisers trade tips for getting students past technical hurdles. At times they can sound like a retro gaming cheat code.

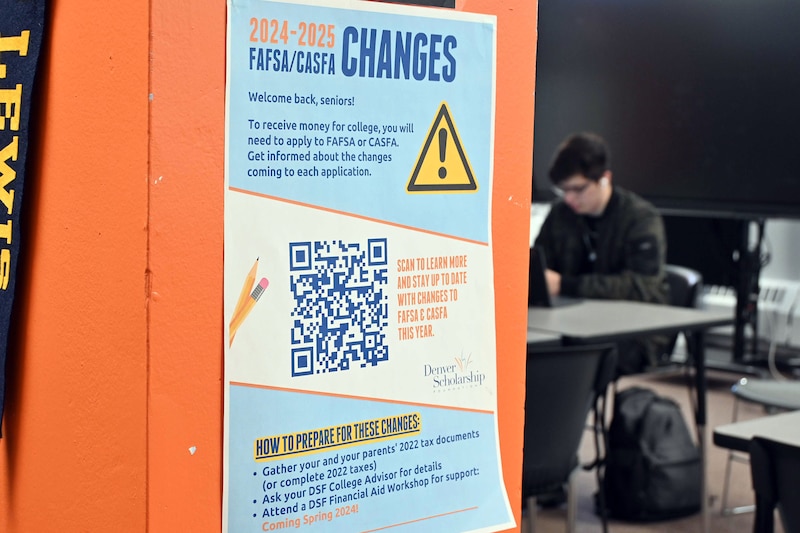

On a recent afternoon at Denver’s West High School, Denver Scholarship Foundation college adviser Federico Rangel shared a hack with student Rene Torres, who was getting an error message every time he tried to add his parents to his account, a necessary step.

“You press the backspace button twice,” Rangel said to Torres. “It should take us back to the original page and then we can move forward. It then should allow us to make the account.”

At first, the trick didn’t work, but then Torres got a new screen for the first time.

“Oh,” Rangel said. “You got the identity verification page.”

“It’s a step in the right direction.”

Many students don’t have financial aid packages

The federal education department has also been slow to share student data with universities and recently announced it would be reprocessing many forms to correct discrepancies in tax data. The Chronicle of Higher Education reported that college financial aid officers are encountering a lot of mistakes, leading to more delays and frustrations. Colleges don’t want to send out financial aid packages that they later have to change.

In a typical year, students would get financial aid packages alongside college acceptance letters and would have weeks or months to compare offers and weigh their options. This year, students have acceptance letters from colleges but in most cases no financial aid awards.

“Students decide where to go and whether to go on the backs of these award letters,” said Bill DeBaun, the National College Attainment Network’s senior director for data and strategic initiatives. “You’re looking at these various pathways with no idea which ones are accessible to you.”

For counselors, this means they’re still working with seniors instead of starting to work with juniors on their college essays like they normally would. It’s harder to hold in-person “complete the FAFSA” events when families might just leave frustrated. And keeping track of shifting deadlines has become its own headache.

For students, not being able to decide on a college can delay or complicate other decisions.

Mark Stulberg, director of college counseling at Newark’s Lincoln Park High School, said students’ attempts to line up housing, internships, and other aspects of college life for next year are all “kind of on pause right now.”

Lincoln Park is part of the North Star Academy Charter School system, where most students are Black and from low-income families. The schools emphasize college-going starting in kindergarten.

This year, 85% of students have completed the FAFSA, a rate far above the state average but still 5 to 10 percentage points lower than in a typical year for North Star.

Stulberg said teachers and counselors are doing everything they can to encourage students to have patience and see the delays as a relatively small bump in a long journey. So far, families are sticking with the process.

Yet he’s worried some of his students “will have put in the last 10 to 12 years worth of work to prepare themselves to be successful in college” only to choose another path that won’t set them up for success like higher education can.

Counselors tell students: focus on long-term goals

Wozniak in Indiana said his team of college advisers, who staff hotlines and events, want parents and students to know they’re not alone, and it’s not their fault. Many colleges and state financial aid systems are pushing back deadlines to accommodate the delays, and financial aid offers will come.

Powell said counselors can help students apply for other scholarships while they’re waiting, or go over how to read a financial aid offer so they can compare options in a shortened time frame.

Rojas Linares is trying to remain upbeat. He has been accepted to a number of public and private universities, though he’s in limbo until he can find out his Pell grants, work study, federal loans, and his award through the New York State Tuition Assistance Program.

“How much longer do we have to wait to get the results of financial aid?” Rojas Linares wondered. “I’m just hoping this will all be over so we don’t have to stress about it any more.”

Mutan is determined to go to college but may end up waiting a year if she doesn’t get financial aid information soon, she said. Her parents are Palestinian immigrants who mostly speak Arabic, and her father provides the household’s only income. She doesn’t want to put financial pressure on her parents, and she doesn’t want to take on debt.

“I want to be able to put myself through college, and FAFSA is a big part of that,” she said.

Chalkbeat journalists Amy Zimmer and Michael Elsen-Rooney in New York, Catherine Carrera in Newark, Carly Sitrin in Philadelphia, and Jason Gonzales in Colorado contributed reporting.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.