Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Pam Little describes herself as Christian and conservative. The proud fifth-generation Texan is no fan of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

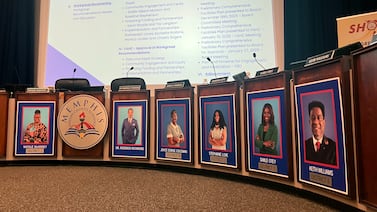

But when the Texas State Board of Education approved a new curriculum last November that draws heavily on biblical material for elementary language arts and reading instruction, Little voted against it. She supports the teaching of biblical values in school, and her objections to Bluebonnet Learning are primarily pedagogical. But Little says some of the lessons that include extended passages directly from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount and the Book of Genesis simply go “too far.”

“This is a sort of no-man’s land that we’re in,” Little said in an interview. “We’ve never had instructional materials that have had this much religious content.”

Some Christian conservatives might not share her concerns. But Texans from a range of religious faiths, including other Christians, raised objections to Bluebonnet throughout the adoption process. A recent Supreme Court decision gives new standing to parents who have religious objections to classroom material and could complicate attempts by states to include more religious content in public school instruction.

In a 6-3 decision in Mahmoud v. Taylor, the court upheld the right of parents in a Maryland school district to opt their children out of lessons involving LGBTQ characters and themes that don’t align with their religious beliefs. The Supreme Court’s ruling laid the groundwork for a constitutional right for parents to opt their children out of classroom instruction that potentially conflicts with their religious faith.

Opt-out policies have traditionally been championed by conservative groups, including some of the very same groups in Texas that support Bluebonnet. Emboldened by the Mahmoud v. Taylor ruling, conservative groups are encouraging more parents to ensure their districts let them opt their kids out of LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. But efforts in Republican-led states such as Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana to infuse more religious content in public instruction — including biblical lessons and requirements to display the Ten Commandments in classrooms — are spurring a wider range of parents to express religious objections.

School districts aren’t required to use Bluebonnet, but adoption comes with additional state funds. The Texas Education Agency, which developed the curriculum, has provided little guidance to school districts that have adopted Bluebonnet, but told Chalkbeat that districts “must follow the law” regarding opt-outs.

The Mahmoud ruling doesn’t fundamentally alter relevant Texas law. Since the mid-1990s, state law has allowed families to exempt their child from instruction that conflicts with a family’s religious or moral beliefs. But parents can’t opt their children out of entire semesters worth of learning, and Bluebonnet’s religious content is deeply interwoven throughout the elementary school curriculum.

Texas education officials and supporters of the curriculum maintain that Bluebonnet Learning is not a religious curriculum. The Biblical references are designed to help students understand literature, history, politics, and culture, they say.

While they support parents’ rights to opt their children out of classroom instruction, supporters see Bluebonnet as fundamentally different from the LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum at the heart of Mahmoud v. Taylor.

Those LGBTQ-themed books, they say, are inherently “ideological” and encourage kids to accept ideas that go against their religion’s teachings. By contrast, learning about the story of the Good Samaritan exposes children to an important cultural touchstone and teaches universal virtues of kindness and tolerance, Bluebonnet supporters say.

“I, for one, cannot understand why any parent living in the greatest country that’s ever existed in the world would not want their child to understand the foundations, the historical references that are included in the Bluebonnet curriculum,” said Mandy Drogin, an education expert with the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank involved with the curriculum’s development.

Parents and administrators are navigating how public schools promote shared values in a diverse and polarized society. Whether to opt out of lessons can feel high stakes and personal, and it can involve a lot of work for parents.

Sikh parents and community members fear that Bluebonnet will leave children feeling even more isolated than they do now, said Upneet Kaur, the senior education manager at the Sikh Coalition, which is working with Sikh parents in Texas who are concerned about Bluebonnet.

“Sikhs already have a very large amount of bullying that they face in classrooms due to a lack of understanding that students and educators may have of their identity,” Kaur said.

Do Bible references promote religion or cultural literacy?

Bluebonnet Learning was developed by the Texas Education Agency to reduce teacher workload and offset district costs. Its materials include readers, classroom activities, and evaluative material for grades K-5 in reading language arts, as well as math instruction.

The curriculum has attracted controversy for its usage of religious references throughout lessons that are aligned with state standards. A kindergarten reading lesson on sequencing asks students to order the days described in the Book of Genesis. A fifth grade art lesson on Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of the Last Supper directly cites the Book of Matthew.

School districts across Texas are now in the process of deciding whether to adopt materials from Bluebonnet Learning for the upcoming school year. Those that do will get an extra $60 per student.

The Texas Education Agency maintains that “there is no religious instruction in Bluebonnet Learning.” Supporters contend that religious references are part of a model of classical education that is intended to provide students with the cultural literacy to better understand American history and literature.

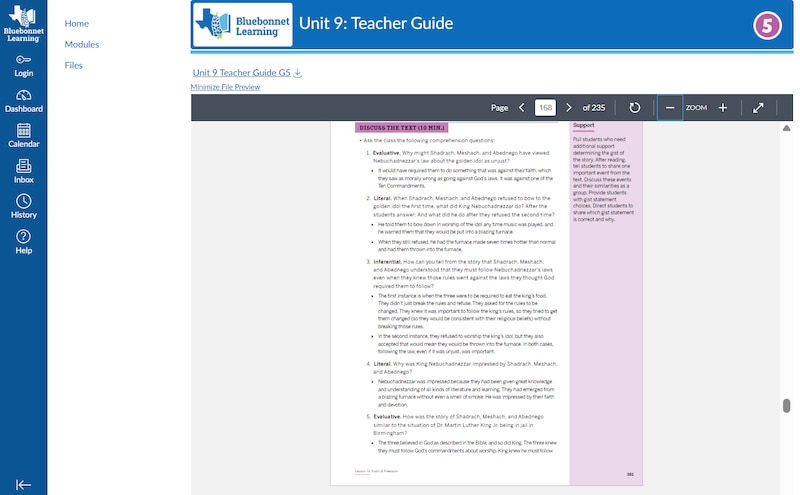

For example, fifth grade reading material on Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail asks students to also read the Book of Daniel, which King cites in his letter to justify the practice of civil disobedience in response to white Christian clergymen who criticized the nonviolent protests.

“It’s about informing children to be a well-rounded Texan, to be a well-rounded American, it’s important that they have some sort of context of these culturally significant stories,” Drogin said. “You can’t understand the Letter from the Birmingham Jail if you don’t have a biblical understanding.”

But Little, the state board member, who previously worked in educational publishing, said that “Bluebonnet Learning misses the whole point of his letter and it bothers me that it just talks about his faith in Christianity and that’s not what his letter was about. His letter is telling white Christian people to get up and start to help.”

Critics contend that Bluebonnet’s references to the Bible are treated as historical fact and are cited more often than religious texts from other belief systems.

Students could get the impression “that Christianity is the only religion that is worth knowing about,” said David Brockman, a scholar at Rice University’s Baker Institute’s Religion and Public Policy Program.

Lisa Epstein, director of the Jewish Community Relations Council at the Jewish Federation of San Antonio, said some Jewish parents could construe certain Bluebonnet lessons as “obstructing or interfering with their right to the moral and religious [upbringing] of their child” and may wish to opt their children out of them.

Writing for the majority In the Mahmoud ruling, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito affirmed families’ freedom to remove their child from “instruction that poses ‘a very real threat of undermining’ the religious beliefs and practices that the parents wish to instill.”

On its website, Texas Values, an organization that advocates for biblical values in Texas government, cites the ability for parents to opt out as one reason districts should feel comfortable adopting Bluebonnet.

But in an interview, Mary Elizabeth Castle, the director of government relations at Texas Values, said she hopes parents don’t go that route.

“It would be unfortunate if a parent were to opt their child out of these lessons merely because of these biblical references when there’s a lot more that is covered in the material and actually is supposed to help students excel,” Castle said.

Parents face challenges exercising their opt-out rights

Despite existing state law, opt-outs in Texas happen infrequently, said Kevin Brown, executive director of Texas Association of School Administrators and a former superintendent.

“The overwhelming majority of parents will never opt out and a lot of parents who may even have different religious beliefs are going to say: The school’s going to deliver its standard curriculum and we’re going to raise our kids at home like we see fit,” said David DeMatthews, a professor of educational leadership and policy at the University of Texas and the director of the Cooperative Superintendency Program.

But it’s possible the Mahmoud ruling will disrupt that pattern by raising awareness of opt-out policies, said Rocío Fierro Pérez, political director of the Texas Freedom Network, who has been working with families to understand their opt-out rights.

Due to a recently passed state law that also bans all practices deemed to rely on DEI in schools, Texas school districts soon will be required to inform parents about their parental rights and provide parents a copy of their instructional plan at the beginning of each semester.

Even so, actually exercising those rights is a different matter, advocates say.

Bluebonnet Learning includes Family Support Letters to be sent home in English and Spanish before each unit, giving parents the chance to reach out to teachers if there is content they may want to opt out of. Yet critics say these letters consistently understate the role of Christianity in the curriculum, making it hard for parents to make an informed decision.

“Parents don’t have the opportunity or time to really sit there and parse through all of that material, especially for all the different grade levels,” said Kaur of the Sikh Coalition.

Language barriers are also an overlooked issue when it comes to opt outs.

While in middle school in Texas, Kaur remembers awkwardly translating her sexual education opt-in forms for her parents, who spoke Punjabi. “To see that ten years later not much has changed says a lot about the process,” she said.”

Trung Huynh, a Buddhist monk and adjunct professor of religious studies at the University of Houston, is creating bilingual opt-out forms for parents in his Buddhist community. He said they are wary of their children being taught biblical lessons, but are often too busy with work and lack the English fluency to advocate for exemptions.

School districts lack clear plans for parent opt-outs

Teachers “haven’t been given any direction” for dealing with opt-out requests associated with Bluebonnet according to Malissa Martin, a Texas teacher who switched from teaching literacy to math in opposition to the decision by Conroe Independent, her suburban Houston district, to adopt Bluebonnet Learning.

She’s unsure whether teachers will be expected to shoulder the burden of finding replacement materials for students who have opted out of certain content. Some teachers she knows aren’t even fully aware of the district’s opt-out policies.

Some districts are only planning to adopt materials that do not include religious references. When the South San Antonio Independent School District adopted Bluebonnet, Superintendent Saul Hinojosa told a local news outlet that the district plans to remove any content that is “inappropriate” or presents a religious point of view.

But because religious references are used to teach basic literacy skills, revising the curriculum will be far more complicated than simply excising those portions of the curriculum. And doing so could burden districts who originally turned to the free statewide curriculum to offset teacher workload and curriculum costs.

“I think it’s going to be hard for school districts to figure out how students can opt out of religious learning that their parents don’t want them to have with the Bluebonnet curriculum because it’s so interwoven,” Little said.

Many district leaders haven’t had to spend much time on opt-out requests. But Bluebonnet, DeMatthews said, could “kind of throw fuel on an already burning polarization fire in our state.”

Norah Rami is a Dow Jones education reporting intern on Chalkbeat’s national desk. Reach Norah at nrami@chalkbeat.org.