Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

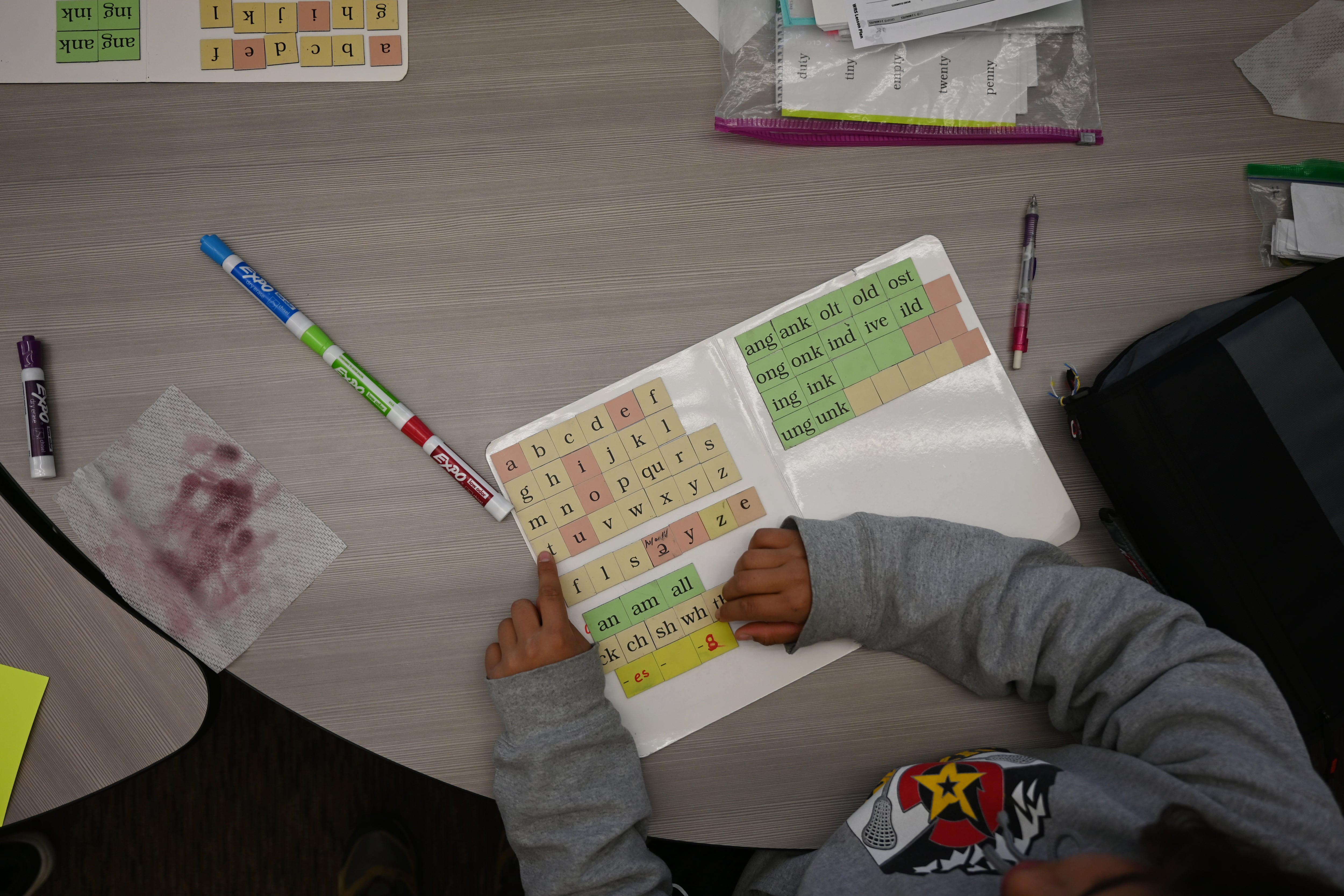

Imagine two elementary students: One struggles to read because she has dyslexia. The other struggles to read because she received poor reading instruction.

The first student is entitled to specialized instruction — after an expensive evaluation process. The second student is entitled to nothing.

In a paper released Tuesday by the Center for Reinventing Public Education, education researchers Ashley Jochim and Alexander Kurz argue for rethinking the special education system and creating a legal entitlement to an adequate education for all students.

Jochim, a principal at CRPE, said she was motivated by professional and personal experience. Working on early literacy initiatives in Oakland, she saw teachers overwhelmed trying to address the disparate needs students brought to the classroom. At the same time, she saw her own daughter, who was diagnosed with dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia, make rapid improvements after switching from a progressive private school to a public school where she received more direct instruction.

“I started to wonder: How many kids are diagnosed with disabilities just because we fail to operationalize good instruction in the classroom?” Jochim said.

CRPE also digitized decades worth of data to chart the rise and fall of certain conditions as eligibility criteria changed. A new data dashboard also released Tuesday shows how widely special education identification varies by state as well.

When the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act passed in 1976, 8% of students were identified as students with disabilities, compared with 15% now. Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder; learning disabilities such as dyslexia; and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, a condition included under “other health impairment” since 1999, have contributed significantly to that increase.

Jochim said parents fight for diagnoses so their child can get an adequate education. She questions whether so much energy and money would be spent on identification if schools had a legal obligation to provide an adequate education to all students.

Large-scale studies found positive outcomes associated with special education services, including greater academic growth. But CRPE points to test score gaps between special education students and their peers that have widened over time.

The paper comes as the Trump administration is considering moving special education oversight to the Department of Health and Human Services, and after hundreds of staff who worked in civil rights enforcement and special education were laid off from the Education Department.

Denise Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, an advocacy group, called the report’s recommendations flawed and the report itself “politically ill-timed.”

Marshall said addressing broader educational problems should not come “at the expense of the rights of students who need and benefit from the lifeline that IDEA provides.”

Chalkbeat spoke with Jochim about these and related issues. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What were the trends that stood out to you in disability identification and what are the policy implications?

There’s this notion in special ed that identification rates represent some true reflection of the number of kids with disabilities, but it’s really not.

A policy change changes the number of kids identified, but it’s not changing the number of kids who need help in the classroom.

We know from national data that there’s a lot of kids struggling in school right now. The vast majority of those kids are not identified for special ed. And the question is: How are we making determinations about who gets help and how should they get help?

We have a huge achievement gap in this country, and it’s really hard to disentangle. What a learning disability diagnosis does is it asks professional staff to make a judgment about the cause of low achievement. In the case of learning disabilities, we say that the cause is based on an innate difference in the child’s brain. We’re trying to exclude all the kids whose low achievement stems from some other, presumably environmental cause.

And there are costs to this. It’s perpetuated siloes at every level of the system, because it’s a totally different set of rules of the game, totally different set of expectations.

Are you suggesting that too many kids are being identified with disabilities? Are you suggesting that we have a problem with overidentification?

I struggle with that word. There is a group of children who are struggling in school. Some subset of those kids are going to get identified, but there’s a whole bunch of them that look very similar, but they don’t get any help. What does it mean to overidentify? The point is helping kids who need help.

I would like to see us move towards a system which is designed to be responsive to students’ needs. Then we don’t have this problem of trying to understand if we’re over- or under- identifying.

What are the features of a system that helps every kid who needs help?

A lot of what we talk about is very consistent with MTSS [Multi-tiered Systems of Support, a framework schools use to identify struggling students and provide escalating interventions]. But we don’t have the resources to back up an MTSS system in practice.

If I could wave a magic wand and change one thing, it would be to root effective instructional practices into teacher preparation programs so that every teacher walks into their classroom knowing how to manage behavior effectively and knowing how to provide really high quality Tier One reading and math instruction.

To be clear, Tier One is not enough. I firmly believe that kids are going to need different amounts of instruction to reach the same end point, because they start at different points. But it would have a profound impact on the system as a whole.

We have seen some states move to universal screening and universal access to literacy tutoring for kids that are deemed at-risk based on the results of one of these screeners. So that’s an example of how this could work.

You call for the creation of a new needs-based entitlement. What could that look like? And what do you think that would do for students?

There’s a lot of programs that target funding and resources to kids who are educationally disadvantaged in some way. Special education is the only one of those that is structured as an entitlement. Schools are obligated to provide you what you need to succeed at school if you are eligible, and money is not a factor that they can consider in this. If they fail to do so, you go to the courts to seek remedies.

This does not exist for any other group of students in America. A needs-based entitlement would help to solve that problem. It would give families real power.

This is not the way to fix everything wrong in education. But if a parent could sue a district for adopting a math curriculum that is misaligned with the science of good math instruction, I’m betting that more of them would spend time getting up to speed on that science and choosing more wisely.

The Education Department has laid off most of the staff that oversee special education. Many advocates are worried about the loss of civil rights protections. Is this a good time to be questioning the underpinning of the whole system?

I am sympathetic to the concerns of disability advocates, and I want to just acknowledge the grief and the fear that exists in this moment. There’s so much happening, and there’s so much uncertainty that I think there is an impulse to preserve and protect what already exists because it feels threatened.

What I have concluded is that we have a situation in which schools can comply with the law and still fail students.

This is the moment to define the future of special education. When we simply defend what already exists, even though what exists is failing so many kids, that’s what fuels the undercurrent of the politics of resentment, the politics of slash and burn. So we really see it as an antidote to this particular political moment.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.