At 7:50 a.m., kindergarten teacher Liz Blaskowski stood by her classroom door inside Westminster’s Skyline Vista Elementary School, ready to greet 17 new students — and take their temperatures. Several miles away, at 8:45 a.m., Denver kindergarten teacher Erika Macias logged on to Zoom to find eight little faces in eight little boxes waiting for her.

Monday was the first day of kindergarten in both Denver and Westminster. But the school days looked very different. That’s because Colorado doesn’t have a statewide strategy for reopening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, each district is following its own plan.

Westminster Public Schools, which serves about 9,000 students, reopened schools for in-person learning. Families who don’t want to attend can opt to learn remotely at home.

Denver Public Schools took the opposite approach. About 10 times larger than Westminster, the 92,000-student Denver district started the school year online. Learning will remain virtual until at least mid-October, at which point Denver may reopen school campuses.

We asked kindergarten teachers in both districts to tell us about their first day. Their stories provide a glimpse into the different ways teachers and students are experiencing school this fall.

Denver Public Schools: “It’s the power of the unmute button.”

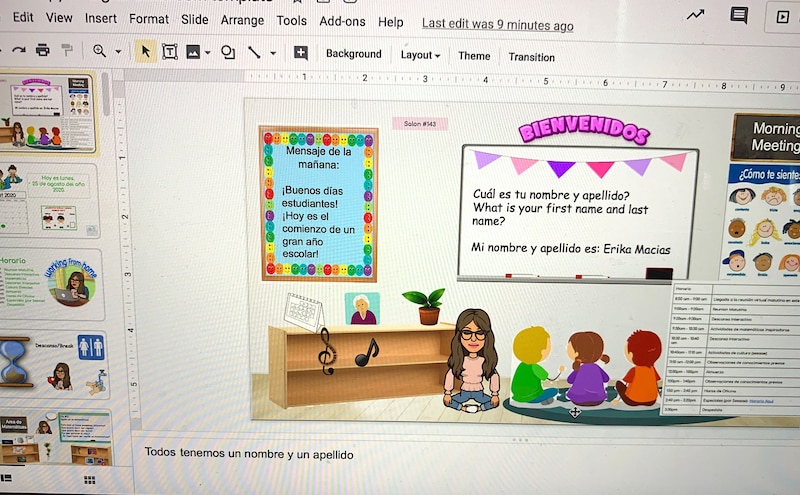

Macias was nervous. She’d heard that Zoom was experiencing nationwide outages Monday morning. From the dining room she had converted into a makeshift office, she clicked the video call link and was relieved to find all eight of her kindergarten students waiting for her.

She knows the students well. Macias teaches at a dual-language Montessori school in northwest Denver. Multi-age classrooms are a key part of the Montessori model, and Macias taught these same students in preschool. This year, they will be the biggest kids in her class, which combines 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds.

They will also be the only kids for the first several weeks. Denver isn’t doing remote preschool this fall. For Macias, that means she’ll only teach eight students online instead of 28.

Macias jumped right in, greeting her students and doing a calendar exercise. Then they sang their morning song, to the tune of “Frére Jacques”: Buenos días, buenos días. ¿Cómo estás, cómo estás? Muy bien gracias, muy bien gracias. ¿Y usted, y usted?

Pretty quickly, Macias realized one of the limitations of her technology: Zoom no longer allows her to unmute her students. She could mute them just fine, but if a student wanted to talk, they had to unmute themselves. Several times, students clicked the wrong button. Instead of unmuting, they turned their cameras off — or worse, hung up the call.

One little girl who likes to hum in class kept unmuting herself while Macias was talking. The little girl explained that she wanted Macias to hear her singing. “I was like, ‘I know it’s beautiful, but can you mute yourself?’” Macias said. “It’s the power of the unmute button.”

Monday’s math lesson was about not giving up. “Sometimes you struggle with math, and that’s OK, and that means your brain grows,” Macias told the students in Spanish.

They watched a video of children struggling with a task but persevering. Macias told the students they were superheroes and had them draw pictures of the source of their strength. The students drew butterflies, flowers, and robots. Two kids drew their dogs.

Their science lesson was about the coronavirus. They watched another video and talked about the importance of washing their hands. The students had lots of questions.

“They’re at that age of, ‘But why?’” Macias said. “They keep asking, ‘But why is it so important to wash our hands? People keep telling us to wash our hands.’ I was like, ‘Because there are germs that get you sick. That’s why you don’t put your hands in your mouth.’ ‘But why?’”

Macias struggled to explain germs over Zoom. Maybe, she said, when they’re back in the classroom, she can set up a science experiment to help them understand.

In addition to a couple of bathroom breaks, Macias also led the class on a show-and-tell scavenger hunt. She gave the students three minutes to find a small object to share. Legos, Barbies, Spider-Man, and a spaceship all made appearances on screen.

By 11:30 a.m., Macias said goodbye.

“They were getting antsy,” she said. Three hours, she said, is “really long on the screen.”

Westminster Public Schools: “Give yourself a hug.”

The day started with school breakfast in the classroom: waffles, cheese sticks and juice — with two children per table instead of the usual four.

Blaskowski, who students called Mrs. B. or sometimes just “teacher,” suggested they place their masks next to them while they ate. Some kept them tucked under their chins so they could pull them on quickly if they had to cross the room to throw something in the trash.

Plenty about the day was typical: Students sat on the floor and listened to “The Kissing Hand,” a picture book about a raccoon starting school. They cheered when it was snack time, they learned how to use a highlighter, and they drew self-portraits during art class.

But there were also differences within the usual school day rhythms. The children used crayons from individual baggies labeled with their names. They sat on Velcro stars spaced evenly apart on the classroom rug. They also stayed in the classroom for most of the day — not heading to the cafeteria for lunch or the art room for “specials.” And when Blaskowski took her own lunch break, she ate alone in an empty classroom, not the staff lounge like she normally would.

Blaskowski, who is in her 11th year teaching, said her students did impressively well in wearing masks, even holding each other accountable for keeping them on. Not one child lost a mask though one student’s ear loop broke, and Blaskowski quickly supplied a replacement mask.

Social distancing was a little harder for the 5-year-olds, especially after lunch as they got tired. At recess, Blaskowski reminded two girls not to hold hands as they headed outside.

“Give yourself a hug,” she said. “Squeeze yourself.”

A couple of children became teary-eyed in the afternoon, homesick for their families. With hugs off the table and her mask making it harder to project, Blaskowski crouched down by one little girl using words more than touch to comfort her.

When it was time to go home at 3 p.m., Mrs. B. didn’t give out high-fives as she usually does.

“It was hard. There was no contact,” she said. “It was a wave.”

But like every year, the kindergartners spilled outside upon dismissal, jumping into their parents’ arms. One little girl chastised her family — she wanted to ride the school bus, not get picked up.

All in all, it was a good day, Blaskowski said.

“I was just happy to be with the kids. They were happy to be here. It felt good. It felt normal — well, not normal,” she said. “It feels like there’s some hope for normalcy.”