In Denver, it was a horse. In one suburban district, it was a cow.

But regardless of which farm animal summer camp staff invoked, the takeaway was the same: For the most part, elementary school-aged kids were able to keep 6 feet apart.

“We’d say, ‘Keep a horse between you!’” said Heather Intres, who directs before-and-after school programs and summer camps for Denver Public Schools.

Her counterpart in the Adams 12 Five Star district, Molly Brandt, said she was surprised by how well the children adapted to an environment of daily temperature checks, social distancing, required mask-wearing, and frequent hand-washing.

“I knew kids were resilient,” Brandt said, “but I had no idea that they would be this happy still, this engaged — laughing, playing, experimenting. They did all the things we typically do.”

The experiences of the two districts provide a preview of sorts for the next few weeks, when schools across Colorado plan to welcome students back to buildings, either for in-person learning or to provide a supervised space for students to do virtual learning.

The summer camps hosted children ages 5 to 12 at local elementary schools. While both camps had their scares, neither experienced a COVID outbreak among children or adults. Achieving that result took relentless effort and long hours — and a little bit of luck. Other summer camps in Colorado and around the country did experience outbreaks.

Brandt recalled getting phone calls at 5 a.m. that a staff member had woken up with a sore throat and runny nose: Should that staff member stay home? Who should cover for them?

“COVID management is 24/7,” Intres said. “There’s never a time when you can not be vigilant.”

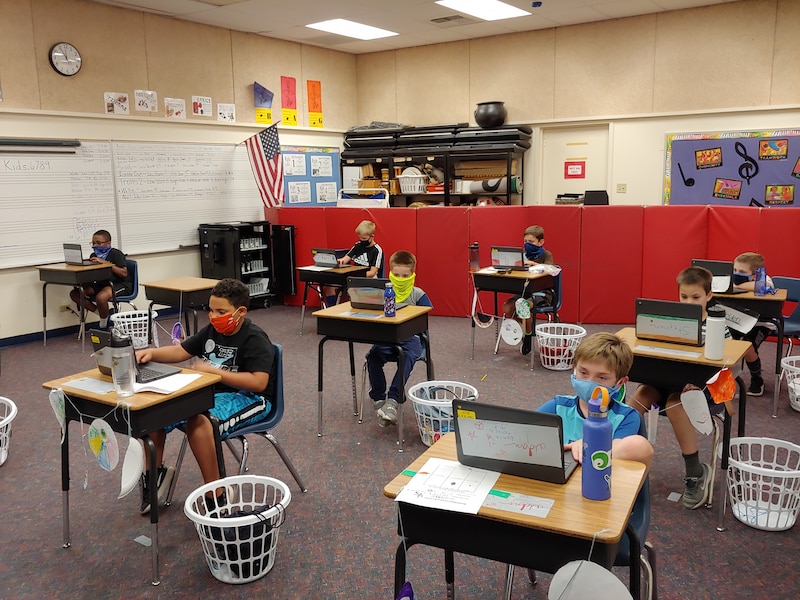

The camps had fewer children than normal, but they still required a lot of adults to run, the directors said. That was partly due to a lower child-to-adult ratio — the camps limited the number of kids in a group to 10 or 12 — but also because staff absences were more frequent.

Adams 12 ran the bigger of the two camps: Nearly 500 elementary school-aged kids attended its BASE summer program over eight weeks in June, July, and August. None of the children got sick with COVID-19, Brandt said. But two staff members did — one before camp officially started and one during the first week that kids were attending.

The second case caused two groups of kids who were exposed to the sick staff member — a total of fewer than 20 children — to stay home for 14 days, Brandt said. Adams 12 didn’t require the children to get COVID tests, but Brandt said some did. The tests were negative and no one developed symptoms, she said. All of the kids returned to camp once their 14-day quarantine was over, Brandt said. The staff member recovered and returned, too.

Although the quarantine was effective, Brandt said the process was intense. A memo from the superintendent says district staff spent nearly 30 hours over Father’s Day weekend contacting co-workers and parents at the sites where the two sick staff members worked to tell them the news, relay quarantine requirements and testing options, and answer questions.

Brandt said she told families: “COVID is living in our community. We knew there was risk when we opened. And we knew we could mitigate that risk to the best of our ability.”

Denver Public Schools had no positive COVID cases, Intres said. Its Discovery Link camp was smaller and shorter: About 180 kids attended for four weeks. Though no one got sick, 12 staff members who had symptoms or were exposed to COVID outside the camp stayed home for two to 14 days while they awaited test results. All of the tests were negative, Intres said.

“Were our protocols super tight? Yes,” she said. “Did we get lucky? Yes.”

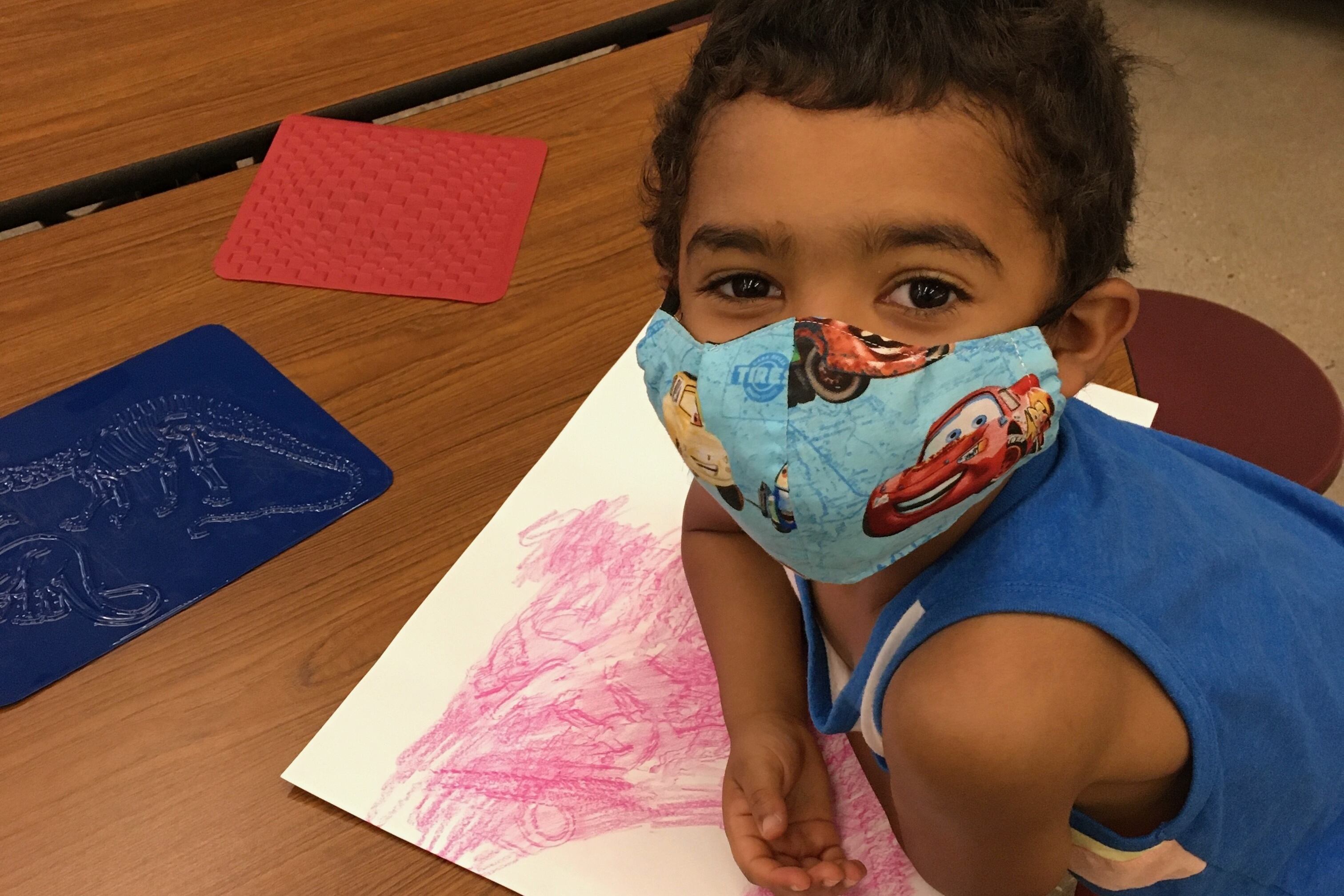

Other lessons learned, the directors said, included the importance of visual cues for young children, such as dots taped to the ground 6 feet apart in the bathroom line. Having masks that fit little faces is also key; Intres said they quickly learned that bandanas and buffs slip down.

But masks also make it harder for kids — especially kindergarteners — to build trust with adults whose faces they can’t fully see, Intres said. To overcome that, she said staff working with the youngest campers started every day with getting-to-know-you activities, asking the kids to tell stories about themselves, their families, their favorite thing they did yesterday.

“We did a lot of check-ins to make sure their day started off with them feeling heard,” she said.

Given that COVID cases were trending upward in July after a dip in May and June, both Denver Public Schools and Adams 12 made the decision to start the school year this month with virtual learning. But some school buildings in each district will be open.

Starting Aug. 17, Denver Public Schools is planning to offer child care at about 65 of its schools for the kids of teachers, principals, and others from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. Instead of 10 kids to a classroom like during summer camp, the child care program will cap class sizes at 15.

And starting Aug. 27, Adams 12 will open some of its schools to host free “learning pods” for elementary and middle school students. The pods are meant to serve as supervised spaces for students to attend virtual classes.

The pods will be open during normal school hours and staffed by substitute teachers, teacher’s aides, or after-school program staff. Elementary school pods will be limited to 12 students each; middle school pods will consist of up to 15 students.

Both programs will serve as an ongoing test of the safety of reopening schools. And the effectiveness of telling kids to stay a horse- or cow’s-length apart.